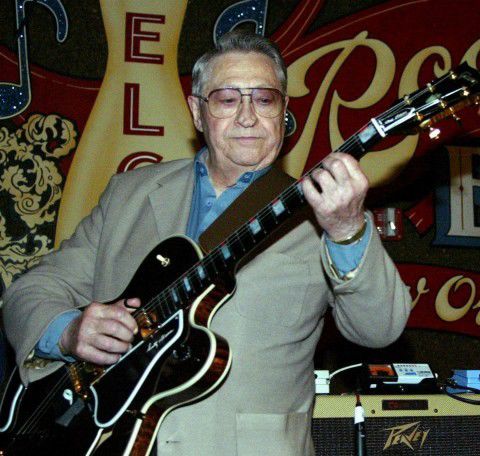

Scotty Moore, who helped ignite the rock-and-roll revolution in the mid-1950s with his electrifying guitar work on Elvis Presley’s first recordings and who practically invented the vocabulary of the rock guitar for generations to come, died June 28 at his home near Nashville, Tennessee. He was 84.

He had kidney ailments and a heart attack, among other recent health problems, said his biographer, James Dickerson.

In 1954, Moore was a self-taught guitarist and Navy veteran struggling to find a foothold in the music world. He and his country band, the Starlite Wranglers, had worked in Sam Phillips’s Sun Records studio in Memphis, and Phillips passed along the name of a young singer interested in making a record.

Moore called the 19-year-old Presley at home and invited him to his house for a rehearsal. The next day, Presley showed up and sang a few songs with Moore and Bill Black, the bass player from the Wranglers.

A day later, on July 5, 1954, they went to Sun Records and tried without success for several hours to cut a record. It was getting late, and the three musicians – Presley, Black and Moore – had to get up the next morning to work at their day jobs.

“All of a sudden, Elvis just started singing this song, jumping around and acting the fool,” Moore told author Peter Guralnick for his 1994 biography, “Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley,” “and then Bill picked up his bass, and he started acting the fool, too, and I started playing with them.”

The song was “That’s All Right,” a blues tune recorded in the 1940s by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup. Phillips poked his head of the control booth and asked what they were doing.

“And we said, ‘We don’t know,’ ” Moore recalled to Guralnick. ” ‘Well, back up,’ he said, ‘try to find a place to start, and do it again.’ “

They worked out an arrangement on the fly, Moore improvised a guitar solo, and the result was an exuberant, high-spirited performance unlike anything else that had come before.

When Phillips played back the recording, Moore said, “We couldn’t believe it was us. It just sounded sort of raw and ragged. We thought it was exciting, but what was it? It was just so completely different.”

As Guralnick wrote, “nothing had been said, nothing had been articulated, but everything had changed.”

A few days later, Presley, Black and Moore recorded a propulsive version of “Blue Moon of Kentucky” by bluegrass artist Bill Monroe as the B side to “That’s All Right.” The records began to get radio airplay in Memphis, and Presley’s first live performance – backed by Moore and Black – occurred on July 30, 1954.

The trio kept returning to Phillips’s studio for more than a year, later joined by drummer D.J. Fontana, recording about two dozen songs, including “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” “Baby, Let’s Play House” and “Mystery Train,” that have become known as the Sun Sessions.

After Presley’s contract was sold to RCA in 1955, Moore and the other Memphis musicians continued to work with the singing star for another two years, recording such seminal songs as “Heartbreak Hotel” “Hound Dog,” “Blue Suede Shoes” and “Jailhouse Rock.”

Moore’s slashing, metallic-sounding electric guitar was an essential part of almost every tune that Presley made famous. His solos invariably drew an enthusiastic response and were a key element of Presley’s early renown.

He recorded about 300 tunes with Presley in the 1950s and 1960s, and Rolling Stone magazine listed him at No. 29 among the 100 greatest rock guitarists in history.

Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones was 13 when he heard Moore’s guitar on “Heartbreak Hotel.” “I knew that was what I wanted to do in life,” he later said. “Everybody else wanted to be Elvis. I wanted to be Scotty.”

Winfield Scott Moore III was born Dec. 27, 1931, near Gadsden, Tennessee. He grew up on a farm, learning to play guitar in a musical family.

He picked cotton as a child and quit school in the ninth grade. At 16, he joined the Navy, lying about his age. When he returned to Memphis in 1952, he hoped to play jazz, and his strongest musical influences included jazz guitarists Tal Farlow, George Barnes and Les Paul, as well as country star Chet Atkins.

While trying to make his way as a musician, Moore worked in a tire factory and at a family-run dry-cleaning business. After leaving Presley over a salary dispute in 1957, Moore ran recording studios in Memphis and later in Nashville, where he settled in 1964.

He occasionally recorded with Presley in the 1960s and appeared on the singer’s landmark comeback TV special in 1968, then put down his guitar for more than 20 years. He engineered recordings for Ringo Starr, Dolly Parton and other performers.

“For 20 years after Elvis died [in 1977], he wouldn’t talk about him, wouldn’t give any interviews,” Dickerson said Wednesday. “He didn’t want to seem to be cashing in.”

Moore began to play guitar again in the early 1990s at the behest of Carl Perkins, another Sun recording star from the 1950s. In 1997, Moore reunited with Fontana, the drummer from the early days in Memphis, for an album called “All the King’s Men,” featuring Richards, Levon Helm and other musicians.

Moore’s three marriages ended in divorce. A longtime companion, Gail Pollock, died in November. Survivors include five children and several grandchildren.

In 2000, Moore was elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the inaugural class of the “Sideman” category. Black, who died in 1965, and Fontana were inducted in 2009.

Moore never liked being called a sideman, but he recognized that his musicianship and Presley’s charisma together created something new and powerful in music.

“Fast music was what I liked,” Moore said in his 2013 memoir, “Scotty & Elvis: Aboard the Mystery Train.” “For years I had been making up guitar licks for uptempo music. . . . It wasn’t until Elvis . . . that I suddenly knew where those licks belonged.”