Every house has a junk drawer or two. Some have junk closets or even entire rooms filled with “things,” but often those things are keepsakes and carry sentimental or family historical significance: photos meant for framing; a gadget that is missing an essential part that makes it operate; knickknacks that for some reason you can’t bring yourself to throw away.

In my home growing up the junk drawer could be found in an unlikely and strangely out-of-place location – in the dining room, in a rather fancy cabinet. The cabinet held china, crystal and, yes, junk.

Like a lot of junk drawers, this one held some history along with the paper clips, pens, pencils and faded photographs (a picture of my mother taken at a beach when she was a teenager remains in my memory). The history came in the form of mementos from my father’s time in “the war,” World War II. Thoughts of him and that time came rushing back over the Memorial Day weekend.

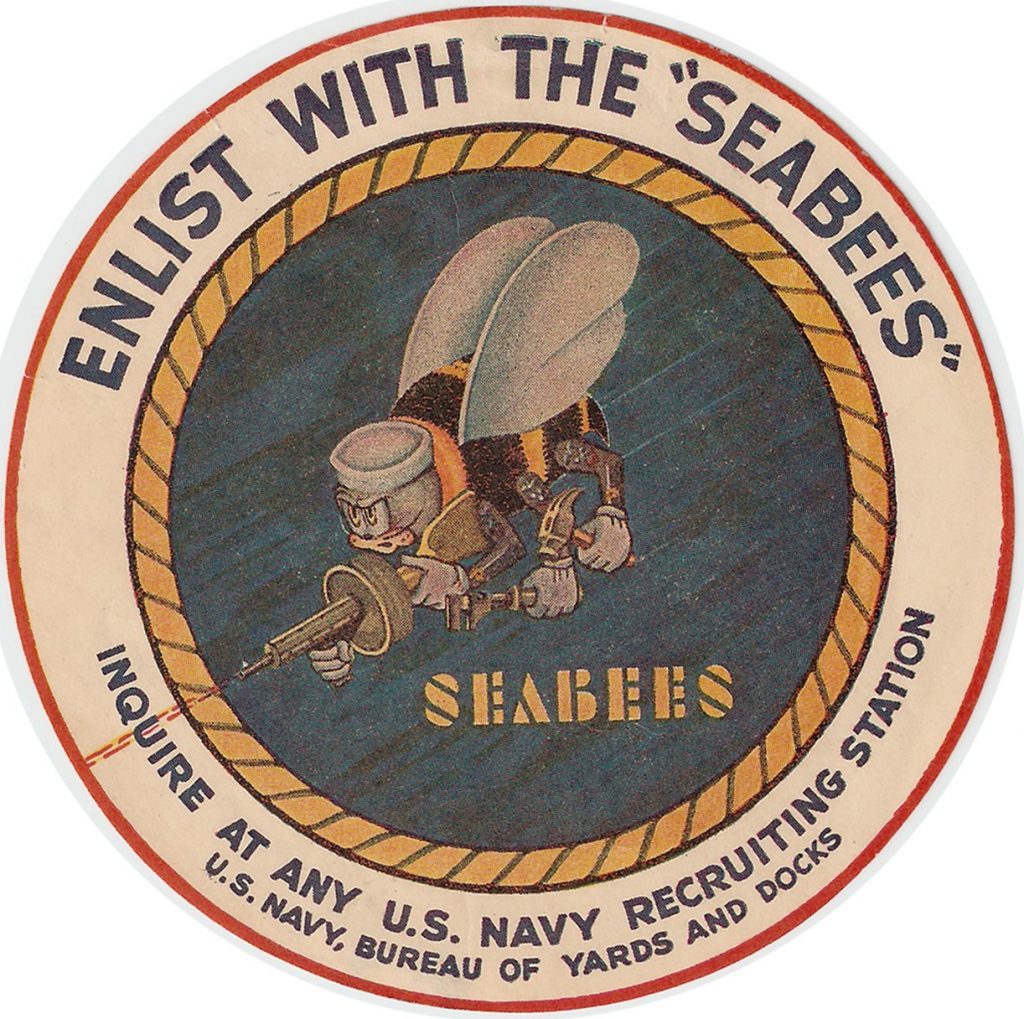

My father was in the Navy’s Seabees, a construction unit, and he served in the Pacific. There were some medals and decals with the Seabee insignia, a busy and angry looking bee. I loved looking at them and trying to imagine what my father’s life was like back then.

Imagination was all I had because we did not talk much about his time at war. Fumbling through the drawer I was reminded why we did not talk about it. Such taciturnity, of course, was characteristic of the Greatest Generation that fought World War II.

There were hearing aids in the drawer, vintage 1940s, and as you might imagine they were bulky, awkward, hideous, and sad looking. They were my father’s. He did not wear them.

My father enlisted, I believe, right after Japan’s Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. My oldest brother was about to turn 2 at that time. My second brother would be born in 1942.

Even with a child at home and one on the way, my father enlisted anyway. My oldest brother for several years referred to him as “the man in the jeep,” the vehicle he would drive, I guessed, when on leave. My father harbored a belief that my brother, in the recesses of his mind, resented his leaving for the Navy.

Although my father didn’t talk about the war he did talk about about his time in the service. He told hilarious stories about the characters he served with and usually around Christmas some of them would phone our house or my father would phone them. My father was six-foot and rugged and remained that way his entire life, with piercing blue eyes and jet black hair. He played football in college and with a semi-pro team in Boston and he played hockey, although he could barely skate. He was an early “enforcer.” He told stories about bartending during the war at what I guess was the officers club and his tales of boxing matches among the sailors, him included, were thrilling. He could still throw a punch at age 60, as he demonstrated at the racetrack one day when he decked a guy who was harassing someone who was obviously frightened. One punch and the bully went down.

If you only knew the stories about the good times he had, you’d think my father had it easy in World War II. Not so.

He was on a ship that hit a mine and was blown up. He floated for a couple of days and literally was washed ashore on a beach. When he regained his senses, he could no longer hear. I have no idea how he was rescued.

Eventually, some of his hearing returned but he spent much of his later naval service learning and then teaching lip-reading. Always made me nervous when I was whispering to someone.

One night when I was about 13 my friends and I asked him to tell us about the war and he described what he could recall about the ship explosion. That was the first real war story I ever heard him tell and it was also the last.

The next morning my mother asked that I never bring it up again.

“Your father had terrible nightmares last night,” she said.

Still, I wish I knew more, and my guess is that there are many among us who wish they knew more about the wartime service of their parents and family members. I was of the Vietnam generation, had orders to report to the draft board when the lottery saved me. None of my friends who served in Vietnam have ever wanted to talk much about that war, either.

Whatever we may or may not know about the horrors of war, Memorial Day gave us a precious moment to stop and stand in awe of those who have served our country and those who still do. We owe them more than we can ever say – or that they want to say.

– Richard L. Connor