For months, Randy Walden peddled a 30-week course in manufacturing at Truckee Meadows Community College, in its warehouse campus by Reno-Tahoe International Airport.

He called job prep agencies looking for students and plugged the class on the school’s website. Two people signed up. It took him four weeks to drum up four more.

“I was getting ready to cancel it,” he said.

Then in September, electric carmaker Tesla announced that it would build the world’s largest battery factory, or “gigafactory,” outside Reno, Nevada, where with its partner Panasonic — which will manufacture the lithium battery cells that Tesla will bundle into battery packs to run its cars — would hire 6,500 employees.

The phone calls poured in to Truckee Meadows. That first class grew to 14 people. The second has 45, with a nearly 400-person wait list.

For Tesla and Nevada, success will depend on quickly deploying a skilled workforce of many more.

Tesla’s agreement to a $1.3 billion incentive package to build its factory set off a frenzy to prepare Nevadans for the jobs their taxes are now subsidizing at a rate of $190,000 per position.

The Tesla deal is one of the nation’s top economic development prizes in a decade. In Nevada, one lawmaker told Reuters, it’s the “biggest thing” going “since at least the Hoover Dam.” Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval and state lawmakers project that over 20 years it will create 20,000 jobs and generate $100 billion for the state, which suffered in the recession.

But the agreement also comes at a time when economists and academics are questioning the wisdom of making big-ticket bets on single companies.

For all the promises of jobs and growth, Tesla’s founder, Elon Musk, says the company isn’t likely to be profitable until 2020, when he hopes to sell 500,000 cars a year. Tesla reported last week that it sold a record 10,030 cars in the first quarter.

The match of America’s buzzy electric carmaker with a town whose best-known industry features weathered casinos would be less stark if Northern Nevada was already a hotbed of engineering or advanced manufacturing.

It is not. Nevada ranked last in the country in the percentage of its workforce that is in science, technology, engineering and math occupations, according to a 2014 Brookings Institution report. Only 15 percent of its workers are in those fields, compared with 21 percent nationally.

“Our biggest concern is capacity,” said Jim New, dean of Truckee Meadows, who has twice toured Tesla’s car plant in Fremont, California, to get a better idea of its needs.

By fall, the school plans to renovate the warehouse to expand capacity, open on Saturdays and allow students to come in anytime between 7 a.m. and 9 p.m. “We’re talking about preparing thousands of people every semester, when normally it would be 50,” New said.

Reno’s biography is one of booms and busts: silver-mining in the 1850s, divorces a half-century later, casinos beginning in the 1930s and housing during the real estate bubble, fueled by cheap land and easy mortgages.

Nevada was dragged low by the housing crash and recession, leading to an unemployment rate of 13.7 percent late in 2010, four points above the national average. As of January, it still had the highest joblessness rate of any state, at 7.1 percent.

The arrival of the stock market darling has created optimism among locals that Reno could be an outpost of Silicon Valley, anchored by Lake Tahoe and the Burning Man festival. The median price of a single-family home is one-third that of the Bay Area. It boasts more than 300 days of sunshine, and locals brag about hitting the slopes nearby 30 minutes after work. Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak recently tweeted about his ride through the mountains to Reno — in a Tesla, of course.

Nevada secured the gigafactory deal after intense competition from California, Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, all dangling hundreds of millions of dollars in incentives. It triumphed by providing 980 acres of rocky, barren land — donated by a private landowner — access to lithium deposits, tax breaks and proximity to Tesla’s California auto assembly plant.

When it selected Nevada for its factory, Tesla’s stock had soared to more than $280 a share. Twelve years after Musk founded it, the company is valued at around $24 billion.

It was not the first tech firm to land here, but the other big-name firms mostly have back-office operations that employ far fewer people. Apple has a large data presence, and Microsoft’s operations center is nearby. In January, Switch, based in Las Vegas, announced that it would build a $1 billion data center.

Tesla has largely promised Nevada production work, not the high-minded stuff that leads Musk to call it a “software company as much as it is a hardware company.” By 2020 Musk said he would like to produce 35 gigawatts annually of battery power, the accelerant to launch his cars into the mass market.

It seems a far-off goal: The company sold an estimated 18,750 of its Model S roadsters in 2014, at a sticker price of about $70,000. Tesla says the batteries will help it to bring the cost of a future car, the Model 3, down to about $35,000. No one really knows how big the nascent, and competitive, market for electric cars will be. And other auto titans — Ford, Nissan, General Motors — are making inroads.

Making sure that Nevadans land the jobs and that Tesla gets the people it needs will require expansive cooperation between the company, schools and the government. Reno stakeholders are painfully aware of how close the California border is, about 250 miles along the interstate through the Tahoe National Forest, for engineers or managers who would consider a weekly commute.

“I think there is a real possibility that there will be commuter workers,” said Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who co-authored the report on the state’s workforce. “If the skills are not there, then there will not be the quality of the battery product, and that will complicate things both for Tesla and for the State of Nevada.”

A challenge for some educators has been determining what types of workers the companies need and when they will be needed. In its application for subsidies, Tesla outlined 6,500 jobs created over eight years, including 4,550 production associates, 460 equipment technicians, 360 quality technicians and 200 material handlers making $22 to $28 an hour. It also lists 930 jobs for engineers and senior staff making an average of $41.83 an hour, or $80,000 annually.

Since then, New, the dean of Truckee Meadows, was given a more specific breakdown of positions needed, along with qualifications. Among the jobs and descriptions listed are Paint Robotics Technician (requirements: “Expert in robot programming. Good overall computer skills.”) and Inventory Control Manager (“Knowledge of change control processes is a must.”).

Officials also say they expect Tesla to hire about 300 interns, and students who have interviewed said they believed the jobs required working in the Fremont facility and then returning to open the one in Reno.

Taylor Glasgow, 23, an engineering student at the University of Nevada at Reno, said he interviewed to be an operations intern helping to expand the Fremont facility. The school will launch a minor in battery science this fall.”They’re just going so fast,” he said. “I think everyone wants to start off with them.”

In March, Tesla set up at a career fair at University of Nevada at Reno, and more than 200 people got in line, résumés in hand. “It was a three-hour wait for a five-minute conversation,” said engineering student Lander Kennedy, 24.

Tesla’s agreement with the state requires it to make two contributions to education — $1 million to the University of Nevada at Las Vegas for battery-related research and $37.5 million to improve K-12 education.

Ray Bacon, executive director of the Nevada Manufacturers Association, said it will take years for the state to prepare the people needed for the Tesla jobs.

“We don’t have that technical experience, right now, today,” he said. “No one can argue that we do. And if they do, they’re smoking something. So it’s going to take some time to get up to speed.

Interlopers are another concern.

“Forty-nine percent of the jobs could be going to Californians, so to us, California came out smelling like roses,” said Greg LeRoy, executive director the advocacy group Good Jobs First. “They will get a lot of the benefits and none of the costs.”

Steve Hill, who negotiated the deal for Sandoval, said that the state had protected itself in case Tesla’s workforce falls below agreed totals or it fails to invest the $3.5 billion it has committed. Every quarter, an audit of the jobs will be performed, Hill said, and if at least half the hires aren’t from Nevada, all the subsidies come off the table and Tesla would need to repay any benefits it received, with interest. In its first audit, Tesla said it had hired 455 people for construction jobs, 80 percent of whom were from Nevada.

“The $3.5 billion of investment and the 50 percentage of Nevadans are light switches,” Hill said. “They either go on or they go off. And if they ever go off, it’s over.”

Like many software companies, Tesla closely guards its secrets. Construction of the gigafactory itself can be viewed by the public only by driving up a steep rocky trail, passing wild horses and tumbleweed on the way. A dirt berm has been raised on the perimeter, restricting the view, and Stan Thomas, executive vice president of the Economic Development Authority of Western Nevada, said he expected Tesla to acquire the surrounding ridge.

“They’re going to buy the mountains around it so no can see in there,” he said.

Officials for Tesla and Panasonic declined to discuss gigafactory hiring or workforce preparation.

“Right now, we’re focused on building the gigafactory,” spokesman Khobi Brooklyn said. “We’re building in phases and working with a number of partners in our construction efforts. And because we are building in phases, we are constantly modulating resources based on the scope of work at that time.”

But some consider the company’s secrecy a hindrance to job preparation.

Ann Silver, executive director of JOIN, a job training nonprofit group funded by the Labor Department, said that despite a visit from a Panasonic rep, she has been unable to get the information she needs on job descriptions and skills from the companies.

“I don’t want my clients to be the 9,000th person in a line of 10,000 people at a job fair with everyone from North Dakota to Utah to Arizona standing in front of them,” she said.

Silver, a 25-year veteran of corporate human resources in New York, said every company should know what kind of people it will need, at least six months out.

“I understand that priority is supposed to be given, but that means nothing if we don’t do the training and preparation ahead of time,” she said. “How could it ever be too early to train people for these jobs?”

Hill said he has another hedge in case Tesla doesn’t come through: The lithium batteries built in Northern Nevada could be packaged for other electronics and devices.

“People tend to forget that the demand for batteries is more on the renewable energy side than it will be for Tesla’s electric vehicles,” Hill said. “We certainly root for Tesla and hope that works. But the opportunity for both utility sale and distributed generation storage is really much bigger, at least over the next five or 10 years, than the Tesla demand will be.”

There is some debate about that. Richard Chamberlain, chief technology officer of Boston-Power, a global supplier of lithium-ion battery products, said the “18650” cells from Panasonic could “potentially be used in many different applications.”

Other experts have suggested that there is already an overcapacity of lithium batteries and that the market for the Panasonic cells is drying up as designs for laptop computers and tablets evolve.

Either way, local officials have come to believe that Tesla will do more than build batteries. Mike Kazmierski, president of the Economic Development Authority of Western Nevada, said he is already seeing a trail of companies following Musk to Reno.

“Four or five years ago, who would ever want to say that they had a Reno address?” he said.

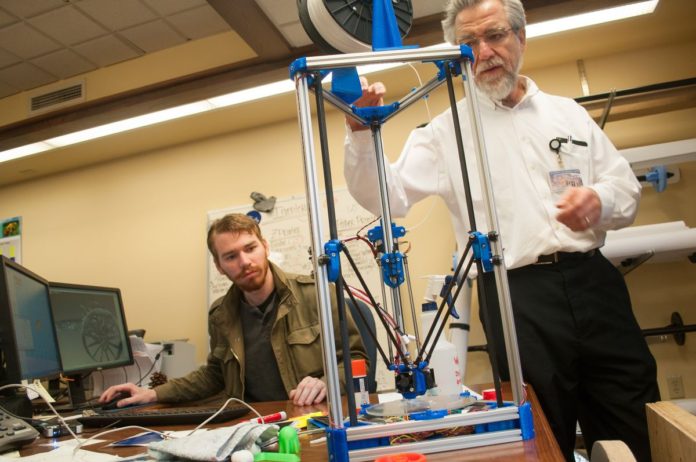

In one of the manufacturing labs at Truckee Meadows, a half-dozen students tinkered with the machinery on a recent afternoon. There was John Leniz, a 45-year-old who owned a brewpub in a local mall that was replaced by the Cheesecake Factory. There was Jessica Irwin, 31, who after a stint selling things on eBay decided to try her hand at manufacturing instead.

And there was Terrence Nearn, fresh off celebrating his 50th birthday, who read about the Tesla factory in the newspaper while living in Orlando. He flew to Reno and moved in with family before starting the course.

“There’s a lot of opportunities for jobs up here,” Nearn said. “But Tesla is the one that really made me take notice.”