WASHINGTON – For Nick and Diane Marson, the story never gets old. Twenty times they’ve seen the musical, and 20 times they’ve discovered something new to savor: another performance, another song.

Another memory.

“We never tire of it,” Diane says on the phone from the Marsons’ home in Texas. “Every time,” adds Nick, “we see something different.”

And how could it be any other way? The Marsons not only revel in the story of “Come From Away.” They also happen to have lived it. Stranded in Gander, Newfoundland, on Sept. 11, 2001 – strangers to each other and the 6,600 other passengers on 38 jets that were compelled by aviation officials to land and sequester on the rugged Canadian island as American airspace shut down – they met and fell in love.

Their romance became one of the many tender threads of “Come From Away,” a fact-based musical by a Canadian-American couple, Irene Sankoff and David Hein, about an isolated community that opened its arms for a shellshocked week to unexpected guests from around the world. It made its debut last year at California’s La Jolla Playhouse and went on to an equally well-received engagement in Seattle. As a result, the show is being readied for a wider audience, on Broadway, in an open-ended run starting in February.

But first, it settles in for a spell at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, where this chronicle of the acts of uncommon kindness committed against a backdrop of unfathomable evil will certainly find an exceptional emotional resonance. Washington, of course, was one of the two cities attacked on Sept. 11, when terrorists’ crashed a hijacked jet into the Pentagon, killing 189 people. Thousands more died in the pair of attacks on the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan and the crashing of a fourth jet in the Pennsylvania countryside.

The musical, which begins at Ford’s on Friday, will be playing here on Sunday, Sept. 11 – the 15th anniversary of the worst terrorist act in the nation’s history. During the run, the show will honor the memory of those who died, with special performances for military veterans and families of the victims. The Marsons will be in town, too, along with several others portrayed in the show, for more viewings of a musical they simply can’t seem to get enough of.

Ford’s is hoping that newcomers to the musical, staged by La Jolla’s artistic director, the Broadway-tested Christopher Ashley, will be just as galvanized – though the mass-appeal potential of a 9/11-themed musical remains an open question. Paul Tetreault, Ford’s Theatre’s director, who lobbied hard to get “Come From Away” into his historic space, as the first Broadway-bound production there in decades, views the show less as a risk than as a natural fit for the company’s mission.

“This story is seminal to our history, to American history,” he says. “That is where all the synergies come together for Ford’s.”

From “Fun Home” to “Hamilton” to “Dear Evan Hansen,” serious-minded musicals – those built around sensitive personal issues or complex chapters of history – are all the rage right now. And even so, a story set to melody that’s linked to events imprinted so wrenchingly on the American psyche, might present a different level of psychological obstacle to some ticketbuyers, especially those who still think of musicals as escapism.

The show’s creators submit, however, that “Come From Away” is not so much about the inhuman horrors of Sept. 11 as about the thoroughly human impulses, to provide help and comfort, that immediately followed. Because the people of Gander – a town of 11,000 souls living next to a major international airport that was pivotal to the Allied effort in World War II – went to remarkable lengths to take care of the passengers, and even a few of the four-legged variety, who were grounded and unmoored from their lives.

“It’s more sort of a ‘9/12’ musical, a response to the moment of crisis,” declares Ashley, who has been with the project since its development at La Jolla. “The show is about extraordinary generosity,” and he adds, given the barrage of news of late about refugees and the worldwide spectrum of sympathetic and hostile reactions to their plights, “the show is more pertinent than ever.”

The musical was born, in a sense, five years ago, on the 10th anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks, when Sankoff and Hein attended a reunion event in Gander, with a grant in hand to interview local citizens and some of the returning passengers. They included, among many others, people like the Marsons and Beverley Bass, an American Airlines pilot, for whom the experience in Gander had been life-changing. The effect on the townspeople was just as meaningful: “Fifteen years later, it’s still as strong or even stronger,” says Claude Elliott, the mayor of Gander then and now.

Sankoff and Hein were so taken with the anecdotes they recorded and the songs they heard at a memorial concert, redolent of the folkways of Newfoundland and the music’s Celtic roots, that their inclination was to turn the story of the stranding into a musical. Forty-five minutes of material were presented at the Canadian Musical Theatre Project at Ontario’s Sheridan College in 2012, the first of a series of workshops in Canada and the United States that allowed the couple to expand “Come From Away” to its current 95-minute length.

A 12-member ensemble, which includes both Broadway stalwarts such as Jenn Colella (“If/Then”) and Rodney Hicks (“Rent”) as well as other veteran actors from the West Coast and Canada’s Stratford Festival, portrays both the Gander townfolk and the passengers. They take an audience chronologically through the week’s events, all the while recounting in first person the characters’ personal travails. A woman whose son is a missing New York firefighter waits in anguish for news; a Muslim man who is an accomplished chef finds himself isolated and under suspicion by other passengers; a gay couple worried about their reception in a remote outpost learn a thing or two about an unlikely global hotbed of tolerance.

Indeed, the reflexive open-mindedness of the local residents forms a motif for the show. It seems a prescription for a well-lived life. As Hein puts it about the citizenry: “They’re simultaneously generous and unsentimental.”

The people of Gander and the surrounding towns not only fed and housed these strangers but also went out of their way to sustain them emotionally, a reassuring sense that goodness remained in the world. The no-nonsense brand of hospitality is summed up by Mayor Elliott, who’s also a character in the musical, and who recounts, in a telephone interview from Gander, how people even turned the keys of their cars over to people they had never laid eyes on before. (Of course, as he also explains, the cars would have turned up eventually, given that Newfoundland is indeed an island).

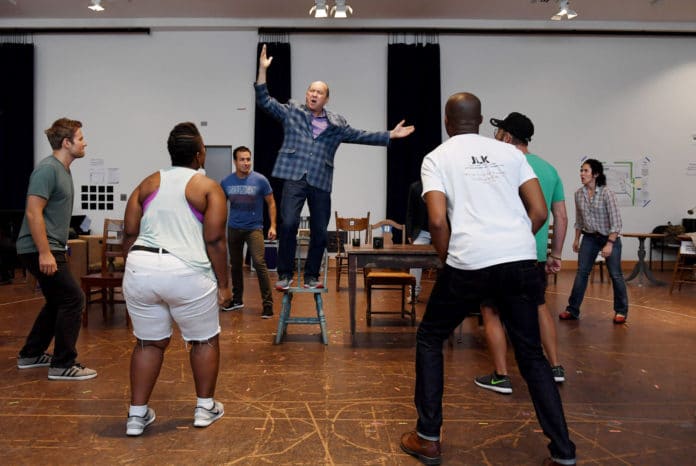

Many of the actors from the La Jolla and Seattle engagements are remaining with the show through Broadway: A Toronto run and a special two-performance concert stop in Gander follow Washington. And they report a deepening bond with both the musical and the people they embody. “It’s an experience like none I’ve ever had,” Colella says, during a break recently at D.C.’s Arena Stage, whose studios Ford’s was using for rehearsals. “I’ve never trusted anything so implicitly.”

She met Bass, the pilot she plays, in California, and found the encounter a lifeline to a more profound grasp of her role, and the stressful situation in which these people found themselves. Of going through the musical’s rituals night after night, and knowing that on many of those nights the people who lived through the events were in the audience, the actress adds: “The biggest challenge is not breaking down.”

Almost as much of a technical challenge: perfecting the odd-sounding Newfoundland accent, in which, for example, a hard “H” is added to a word like “our” and so is pronounced “hower.” The actors, though, realized that the musical was even more of an out-of-body experience for the people they were portraying.

“The first time, sitting in the audience and seeing your life played before you!” Nick Marson says, still marveling at the memory, After that performance, he went backstage and met Lee MacDougall, who portrays him (Sharon Wheatley plays Diane, whom he married a year later). “Lee said to me, ‘It was quite unnerving to play in front of you.’ It was strange for them, but also for us.”

The Marsons become, like others dramatized in the musical, luminaries on these nights. They’re often introduced from their seats, and after a performance are swarmed and congratulated by other theatergoers. They clearly enjoy the supporting parts they have been assigned by “Come From Away,” as enduringly uplifting counterpoints to a time of almost bottomless grief.

Or as Mayor Elliott observes: “On the day of the worst act of mankind, the people who landed here saw the best of mankind.”

—

“Come From Away,” book, music and lyrics by Irene Sankoff and David Hein. Directed by Christopher Ashley. Tickets, $18-$71. Sept. 2-Oct. 9 at Ford’s Theatre, 511 10th St. NW, Washington, D.C. Visit fords.org or call 800-982-2787.