Brazos, still a baby at almost a year old, is a rock star and a thousand pounds of fun. He’s a show-off, a grandstander, a jungle jokester.

“Brazos, you rock, dude. You’re the man.”

He swam every day, almost every hour, of the hot, interminable summer of 2022. Rarely left the pool. Luxuriated in that water. Frolicked. We humans were happy for him but also harbored some petty envy.

Even on this August day that was cooler than most, Brazos was in and out of his pool, rolling in the water, submerging like a fat little baby elephant who thought he was a submarine and having the time of his life.

As Brazos played, he was guarded by his watchful – hovering, you might say – elephant mother, elephant aunt and elephant grandmother. The elephant world is famously matriarchal.

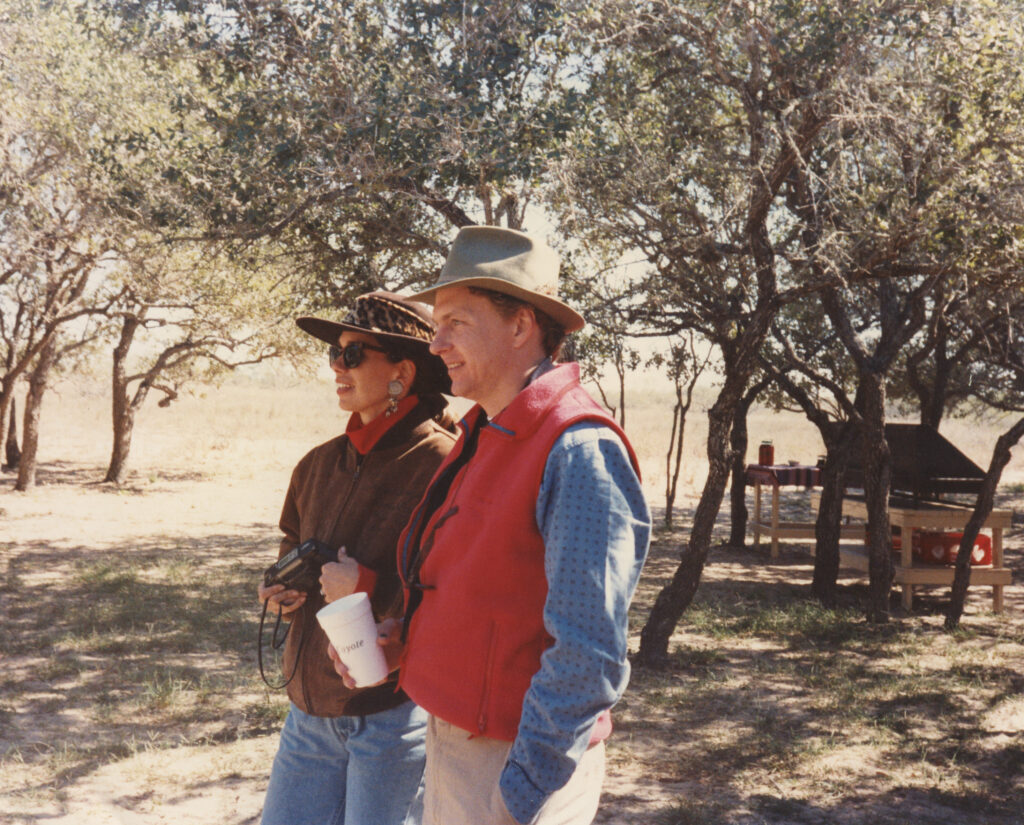

But on the observation deck above and 30 feet away, watching as the protective female elephants tended to the family’s marquee baby and as the crowds elbowed in and lingered, there stood the real matriarch of the elephants and the entire zoo: Ramona Bass.

Big Mama. Mother. Watchdog. Champion fundraiser of our – our, Fort Worth’s – Zoo, which is a national treasurer.

A baby elephant can live like a rock star here because Ramona Bass made it her mission to transform the once-ramshackle Fort Worth Zoo into the finest zoo in America, a showcase refuge where animals are respected, nurtured, loved.

While often given the credit for the reimagined zoo, Ramona is quick to acknowledge everyone who helped. from donors to the city to the zoo staff, the board, Kit Moncrief, Whitney More, Mike Fouraker, Ardon Moore.

But the fact remains that Ramona Bass, through vision, tensile-strength perseverance and dogged insistence, reimagined and rebuilt a civic embarrassment into a municipal crown jewel. It wasn’t easy.

In the mid-to-late 1980s, Ramona and the Fort Worth Zoological Association outlined a plan to privatize management of the zoo, which the city owned but was ill-quipped to run. Along the way, the association planned to add acreage by taking over some nearby parkland that included a popular public soccer field.

Critics arose and a nasty, personal fight erupted over the plan. Residents of neighborhoods surrounding the zoo fought the expansion. Final decisions approving any expansion would be made by city officials but the most inviting target for the opponents’ wrath was Ramona Bass. She was unfairly attacked but she would not back down from her vision for a better zoo and a better Fort Worth.

The critics would have been wise to back off and let Ramona pursue her dream. But they didn’t know about the advice given to Ramona’s mother when Ramona was about 12 years old.

Along with her two siblings she was being tested by a company in Houston called Johnson/O’Connor. The firm specialized in evaluating children to highlight their strengths and weaknesses and project where they might end up in life.

The consultants and counselors were unable to pigeonhole Ramona but the generalization made to her mother was prescient:

“We aren’t sure what she’s going to do but whatever it is you may want to get out of the way. She has the vision and discipline to make it happen and the kind of perseverance to never give up.”

Persevere she did while achieving her goal of building a world-class zoo for Fort Worth. Even when the critics’ heat was on she stayed cool. And all the while, she maintained an aura of dignity and class. She rose above the fray.

Ramona raised over $300 million along the way to save and remake the zoo; she and her husband Lee personally donated $30 million. She didn’t do any of this for personal recognition or gratitude, or to see her family’s name on a building or monument. She just saw a need and got on with it, Texas style.

Lee’s older brother, Sid Bass, had the vision for Sundance Square and downtown Fort Worth, and like Ramona and Lee, left his footprint in invisible ink.

Like any good mother, this matriarch of the zoo takes satisfaction in the success of the children. Brazos is one of her babies. But make no mistake about it. The zoo is her baby.

Ramona has three adult children and …

“My children say the zoo is their fourth sibling,” she says with a charming laugh.

Looking at her warm brown eyes and the Orphan Annie curls that must have played havoc with a little girl growing up in San Antonio, you can hear one of her favorite singers, Van Morrison, singing, “You, my brown-eyed girl … do you remember when we used to sing?”

What we ask is, do you remember when you first visited the Fort Worth Zoo?

If you are Ramona Seeligson of San Antonio, Texas, you do remember when … it was 1983 and you were newly engaged to Lee Bass, a member of one of Fort Worth’s most prominent families. He wanted you to see the city’s zoo.

When you saw it, you were horrified. “It was tired and old fashioned and very depressing.”

Many of the animals were in small cages and looked weakened, she recalls. Worse, they looked sad.

Ramona told Lee what she thought. Not burdened by any reluctance to offer her opinion, then or now, she is direct, with language unfettered but clear. The eyes sparkle and the look is calming but forthright and affirming.

Lee listened as Ramona spoke that day about her disappointment in the zoo. He is quiet and also direct.

“You’ll be living here,” he said. “So maybe you can do something about it.”

Did she ever.

She started by enlisting the aid of noted Fort Worth wildlife conservationist Harry Tennison and his daughter, Kit Moncrief, along with philanthropist Whitney Hyder More. They set about revitalizing the dormant Fort Worth Zoological Association and in 1985 launched what remains the association’s premier fundraiser, the Zoo Ball.

The expansion plan with all the attending controversy proceeded through the late ’80s and in 1990, Zoological Association President Ardon Moore approached the city with what at the time was an innovative plan for privatization that called for the city to retain ownership of the zoo but turn over management to the association. The plan was officially adopted in 1991, and the zoo was shut down for renovations.

The zoo reopened the following year as the “New Zoo in ’92” and continues to grow and rack up awards and accolades as it celebrates 30 years of success this year with an ongoing series of special events and activities.

But Ramona Bass is not resting on her laurels. She is constantly working to make the zoo even better, usually right there on the premises.

She quietly weaves in and out of the small – OK, cramped – office she shares with an assistant (the office is in a trailer on the zoo grounds), often donning her running shoes and walking quickly with the sense of purpose and destination that identifies a woman who notices the details and understands that adhering to minute details leads to monumental results.

She picks up her pace along the pathways to the exhibits, making sure the zoo adheres to the highest standards, only stopping to say hello to employees or maybe even answer a question from a zoo guest who has no idea who Ramona is. She is almost anonymous because she has not overseen the rebranding and rebuilding of the zoo for her own personal benefit or glory.

Ramona is comfortable and confident in who she is and does not confuse her personal qualities and self worth with her identity as architect and leader of the 30-year zoo project that is a gift not only to the city but in fact also to the state and country.

She’s partial to the three generations of elephants housed at the zoo but says with a laugh, “You can fall in love with a green tree frog, too.”

Her favorite exhibit?

“Texas Wild is my heart,” she says.

The exhibit is 20 years old and was built at a cost of $50 million. It pushed the zoo further into education, teaching visitors about the history of the state, particularly in relation to its rich heritage of flora and fauna and complex, natural habitats for birds, insects, deer, hogs, fish, and other forms of wildlife.

Ramona, have no doubts, is fully in charge, a subtle but powerful presence. She knows the animals and she knows the employees, who greet her more as a friend than a boss as she walks the grounds.

After a lengthy discussion with Tripp, an elephant keeper with encyclopedic knowledge about the animals he cares for, Ramona is asked how the zoo finds people such as Trip.

“Ringling Brothers,” she says. “He’s an expert on elephants.”

Details matter to Ramona and her insistence on them carries over to the staff. When elephant experts were needed, the zoo went to the place that specializes in the highest level of care for their animals.

The zoo has reached the pinnacle of success because someone steady and knowledgeable is at the helm, and that someone is Ramona. She works tirelessly and incessantly to improve the zoo – and it should not come as a surprise to anyone that she takes no salary for her work.

The zoo is a big business, with 300 full-time employees and an additional 350 part-timers during the summer. Its annual budget is $40 million. Its average annual economic impact on the city for 2021-22 is $228.5 million.

A love of nature and wildlife does not necessarily translate into business acumen, but Ramona has surrounded herself with highly capable executives to help her steer the zoo’s operations. Executive Director Michael Fouraker has been managing the zoo’s operations for 20 years and is widely regarded as one of the most capable directors in the country.

Ardon Moore, the longtime zoological association president who engineered the privatization deal with the city, is known as an astute financial management expert and savvy investor.

“What many people don’t realize is the broad range of talents that Ramona brings to the table daily, Moore says. “When you visit the Fort Worth Zoo you can see Ramona’s fingerprints everywhere, whether it’s in award-winning exhibit designs, our conservation and stewardship focus, or our many unique visitor amenities.”

Ramona developed her love of animals while growing up in San Antonio as the eldest of Arthur and Linda Seeligson’s three children. The family had a ranch in South Texas where Ramona spent valuable time immersing herself in the marvels of nature and ranching.

Her father made his fortune in the oil business but was deeply involved in the breeding and racing of thoroughbred horses – one of his horses, Avatar, finished second in the 1975 Kentucky Derby and won that year’s Belmont Stakes, the third jewel of thoroughbred racing’s coveted Triple Crown.

Ramona worked with her father in the horse business and remained active after his death in 2001, eventually setting up her own breeding operation and welcoming son Perry Bass II into the racing world. A horse Ramona bred and sold as a yearling for $380,000, Magnum Moon, won the 2018 Arkansas Derby and made it to the Kentucky Derby only to lose, along with 18 other talented thoroughbreds, to eventual Triple Crown winner Justify. She also bred Roy H, winner of the prestigious Breeders’ Cup Sprint in both 2017 and 2018 and winner of both years’ Eclipse Award as thoroughbred racing’s best male sprinter.

“Animals, and especially horses and dogs, are always there-with Ramona,” says lifelong friend Caroline “Cina” Alexander Forgason. “She is animal-driven. And when she gets on a project she gets on it thoroughly. She’s always working.”

Ramona and Cina grew up together in San Antonio and they were roommates at the University of Texas, where both qualified for the Plan II Honors Program, a highly acclaimed and competitive academic program in the liberal arts. Their families literally go back decades and generations – Ramona’s grandfather, a physician, studied under Cina’s great-grandfather, a pioneering surgeon in Philadelphia.

Like Ramona, Forgason knows something about projects and what it takes to make one succeed. She produced the definitive documentary film on John James Audubon, Rara Avis: John James Audubon and the Birds of America, which was featured at the Lone Star Film Festival and also produced for CBS. She watched from afar as Ramona set out to rebuild the Fort Worth Zoo but she had no doubt her friend would succeed.

“She had done her homework on privately run zoos,” Cina says. “She had a clear idea about what could be done. She wanted to bring it into the 20th Century.”

After graduation from UT, Ramona left Texas behind for a year, living in Spain and working as an interior decorator. She then returned to Austin and spent 18 months working for U.S. Sen. John Tower’s reelection campaign before moving to New York City, where she worked as a stockbroker for three years.

By then, ready to return to her roots, she moved back to Texas and took on a challenge that deeply tested her patience, character, resolve and grit.

She was determined to train her own bird dog, an English pointer. A finished bird dog working woods, fields, and coverts is a sight to behold. Dogs have a range of 100 million to 300 million scent receptors (humans have 5 to 6 million scent receptors). Sorting through all those scents in the wild, a good bird dog will focus on a wild game bird or covey of quail and stop dead in its tracks with its nose literally pointed toward the quarry.

Training a dog to work with wild abandon but also to be controlled and even methodical takes skill and a special sense of how to motivate the dog. It takes a “feel,” and the ability to almost think like a bird dog to train one. Most people can’t do it.

Ramona had a goal that was somewhat unusual. She wanted a hunting dog who was also a pet. The idea that a bird dog might hop up on the bed with the trainer, maybe even doze off with its head on the pillow, would be anathema to many hunters.

Ramona successfully trained her “pet/bird dog” and still has that special sense that animals respond to – even huge, thousand-pound elephants.

Once resettled in Texas, she attended a wedding in Mexico with her parents and Nancy Lee and Perry Bass, family friends. There she became reacquainted with a man she had known informally for years – Lee Bass, the youngest of Nancy Lee and Perry’s four sons. Before long, they were engaged, and she was embarking on that life-changing visit to the Fort Worth Zoo.

She had found a cause that married all of her interests and she had found a life with someone who valued her drive and compassion and goals.

“Lee Bass has been an incredible and supportive partner and adviser in all of this,” she says. “I literally could not have done it without him.”

Ramona Bass has had a transformational role in the growth of Fort Worth. She has helped untold numbers of local residents enjoy watching animals they would never have seen – and watching them in exquisite replicas of their natural world. She has led the way in making Fort Worth a destination for tourists and visitors. The zoo has been an enormous economic engine for the city. And let’s not forget the joy experienced by children fortunate enough to attend Zoo School or simply to have celebrated a birthday at the zoo.

Now, three decades after the birth of the “new zoo,” each day presenting challenges that were met with vision and determination, what’s next?

Keep going, says Ramona. Keep raising money. Keep improving and adding to the zoo. She doesn’t have time to articulate any more than that. She’s already moving on to raise the next $300 million. Beyond that all we know is that she may not know exactly where she’s going but it would be wise to listen to the long-ago counselor in Houston: Don’t get in her way.