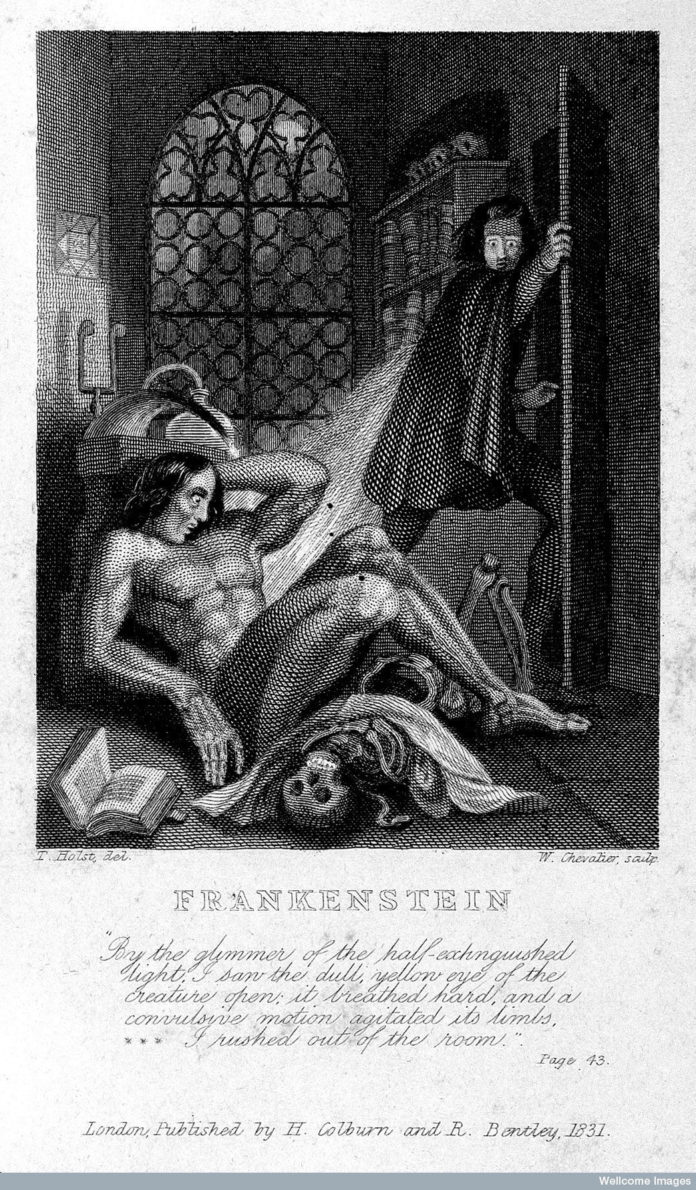

It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils . . . the rain pattered dismally against the panes, and my candle was nearly burnt out, when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open. – Victor Frankenstein

On a similar night in the summer of 1816, a gloomy season darkened by the ash of a distant volcano, 18-year-old Mary Shelley lay in bed, closed her eyes, and envisioned a tale of a madman who builds a monster from human body parts.

“My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me,” she recalled later.

Her reverie would become “Frankenstein,” the Gothic horror story of man’s botched attempt at creation. And this summer marks the 200th anniversary of the night the young English intellectual came up with the idea while on vacation with her lover in Switzerland.

“It’s always been enormously popular,” said Bernard Welt, former professor of arts and humanities at George Washington University’s Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, who has taught courses on Frankenstein.

“It’s one of the two or three most-ordered texts at American colleges and universities,” and has never been out of print, he said.

Shelley wrote later that it was “a wet, ungenial summer, and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house.”

A year earlier, in April 1815, Mount Tambora, a volcano on the island of Sumbawa in Indonesia, erupted in a massive explosion that blasted ash into the atmosphere and resulted in a “volcanic winter.”

Partly as a result, 1816 became the Year Without a Summer, with unusually cold temperatures in North America and cold and rain in a Europe still recovering from the Napoleonic Wars.

Crops failed, and there were summer frosts and starvation. “There’s a lot of evidence that there were messianic cults and prophesies, and people thinking it was the end of the world,” Welt said.

Amid the dismal weather, Shelley and her future husband, the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, passed the time with poet George Gordon Byron and Byron’s physician, John William Polidori, vying to make up ghost stories.

“I busied myself to think of a story,” she wrote years later. “One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror – one to make the reader dread to look around.”

But she thought in vain, she wrote.

Then one night in bed, after a discussion with her friends about the nature of life and the possibility of reanimating the dead, a story came to her.

“I saw – with shut eyes, but acute mental vision . . . the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together . . . the hideous phantasm of a man,” she recalled.

It was a disturbing thought. But the next morning she told her friends she had her story, and wrote a quick draft.

“Mary Shelley has a kind of genius,” Welt said. “She actually takes on the burning, philosophical questions of her time . . . She’s asking questions about the nature of life, and giving life.”

“She and her circle were very, very interested in everything going on in science at the time,” he said. “She talks about the experiments in electricity and the notion that it could animate lifeless matter.”

Mary Shelley wondered: “Perhaps a corpse could be re-animated . . . Perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.”

She referred to “galvanism,” the idea – named for the Italian biologist Luigi Galvani – that an electric current might resuscitate dead tissue.

A famous demonstration had occurred in 1803 when a current was applied to the body of a hanged criminal.

“On the first application . . . the jaws of the deceased criminal began to quiver, and the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened,” according to a prison bulletin that carried an account of the experiment.

“In the subsequent part of the process the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion,” the account continued. “Bystanders thought that the wretched man was on the eve of being restored to life.”

Inspired, Mary Shelley would have her protagonist Victor Frankenstein say:

“Who shall conceive the horrors of my secret toil, as I dabbled among the unhallowed damps of the grave?

“I collected bones from charnel houses; and disturbed, with profane fingers, the tremendous secrets of the human frame.

“The dissecting room and the slaughterhouse furnished many of my materials; and often did my human nature turn with loathing from my occupation.”

The novel was published in 1818, and Shelley’s idea has endured for two centuries as one of Western literature’s great horror tales.

It also gave birth to films such as “Son of Frankenstein,” “Bride of Frankenstein,” and “House,” “Curse,” “Evil,” “Ghost,” and “Revenge of Frankenstein,” to name a few.

In the introduction to an 1831 edition of the book, Shelley wrote that she had affection for her “hideous progeny.”

“It was the offspring of happy days, when death and grief were but words, which found no true echo in my heart,” she wrote.

Nine years earlier, in 1822, her husband had drowned when a boat he was in sank in a storm in Italy’s Gulf of La Spezia. He was 29. She was 24.

Frankenstein’s pages, she wrote, “speak of many a walk, many a drive, and many a conversation when I was not alone, and my companion was one who, in this world, I shall never see more.”