We’re at least a decade into the consensus that television has never been better; “The Sopranos” opened up new possibilities, and shows such as “Transparent” and “Orange Is The New Black” have been considered to widen that aperture, telling new stories with new sensibilities. But as much as television has done to prove it’s a major art form, there have been few efforts to establish a real canon — until now.

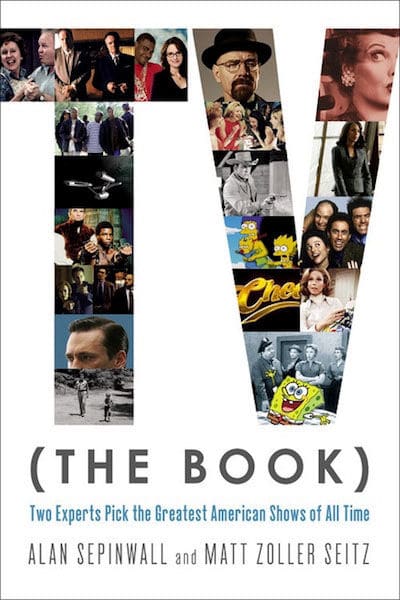

HitFix’s Alan Sepinwall and New York magazine’s Matt Zoller Seitz, who worked together at the Newark Star-Ledger, are out with “TV (The Book),” their stab at defining a top-100 list of shows, with plenty of appreciation for others. It’s the rare ranking book that feels less like an airless proclamation from on high and more like a lively invitation to a rollicking conversation. As Sepinwall and Zoller Seitz argue their way through their top five, or explain what they loved about the shows on their list, there’s plenty of room for argument — and perhaps for subsequent editions. It’s also a fabulous education in what makes television great.

Before the book’s publication, I caught up with Sepinwall to talk about the process of canonizing TV, their ranking systems, and how TV and television criticism have changed over his 20 years in the business.

Q: I wanted to ask, how do you know when the time is right to start establishing a canon?

A: TV’s been around since the ’40s, essentially, and we’re now in 2016. It’s long past time. Someone could have probably done this — someone has, like David Bianculli did a version of this in, I think the early 1990s with “Dictionary of Teleliteracy.” And you could have done it in the ’80s, probably could have even done it in the ’70s. But certainly by now it’s ridiculous that more people haven’t tried to do something like this.

Q: What do you think was the hesitation? I think TV has long had an inferiority complex relative to film.

A: I think that’s absolutely the case and that’s one of the reasons it’s easier to do something like this now, because that inferiority complex is, for the most part, gone. You know, it’s become almost a cliche at this point that movies in the general sense are the place you go for superheroes and explosions and TV is where you go for actual storytelling.

Q: But it’s also interesting that the book is coming out at time when I think there are a lot of questions about the form of television and how it functions, right? The way that Netflix treats everything like a chapter or a 10-hour long movie, it seems like the form is actually kind of fluid in a way that it maybe hasn’t been before.

A: That’s definitely true. The delivery systems alone. I mean, (Louis C.K.’s) “Horace and Pete” is in the miniseries section. You could certainly make an argument, especially if you’re an older person like myself, is that television? I don’t know. I think form-wise, it absolutely is. But if you’re getting really technical, it’s a web series.

Q: Was there some sense that even as you were grappling with this big canon that the form was almost evolving out from under you?

A: It’s one of the reasons we made that rule that, for the most part, the top 100 doesn’t have current shows. They either had to have been around for a really long time like “The Simpsons” or “South Park,” or they had to be in enough limbo, like “Louie” or, ironically, “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” which is now going to make another season, to qualify because things are changing all the time. One of the very last additions we made before the final deadline for the book was in the “Current Shows” section, as “UnREAL” season two was premiering, I said “That needs an essay here. I’m going to write a whole essay on it.” And then “UnREAL” season two was really terrible. So the closer you get to what’s happening in TV now and the ways it’s evolving, the more danger you get into, which is why I like that the canon, or the pantheon, for the most part has some distance from that.

Q: As a critic, it was really interesting reading the opening section of the book where you have the argument over the top five. I was wondering, as you were putting this together, did your sense of what you valued in a TV show, do you feel like it’s changed over time in general, or that it changed at all in this process?

A: I don’t know that it changed in this process. But it was certainly nice because, while I know that Matt and I have very similar tastes, our reasons for having those tastes are different. And so it was nice to have us sort of articulate the reason why he loves “The Sopranos” vs. why maybe I do, or why I might prefer parts of “The Wire” to things he feels about another show. I know that my sensibilities have changed over the 20 years I’ve been doing this, but I don’t know that they changed over the course of doing the book.

Q: How do you feel your sensibilities have changed over those 20 years?

A: I definitely have more of an appreciation for slowness. If you showed the 22-year-old me something like “Rectify,” he would have laughed at it. A lot of the mumble-core-y, not-really-comedies-but-they’re-half-hours about very depressed people, that there’s an enormous abundance in TV right now, I don’t know that I would have had the patience for things like that. But I remember when “ER” was on, when it first debuted, one of the things I really liked about it, I was in college back then, was the fact that patients died. And I said “Well, that’s really different, that makes it feel real, and I like that.” And these days, I’m much older, and now when I watch medical shows or other shows where characters die, it kind of bums me out. So I’m older, I’m a little more patient, I’m more mature in some ways. And so things I appreciate are a little bit different now even though there are still a lot of things that I loved then that I would love now.

Q: One area that I thought was nice to see in the book was a lot of attention on questions about diversity and inclusivity. Obviously those have been a bigger part of the reporting and conversation in our field, I would say, over maybe the last five years in particular. Is that an area where you feel more attuned or aware? Because it seemed like there was a real conscious efforts to consider all those issues in a lot of the sections of the book.

A: Well, I mean, look, we weren’t specifically trying within the top 100 to be inclusive in that area. That was entirely ranking, and it’s a sort of sad reality of TV that there are not a ton of shows with people of color as leads, and certainly great shows with people of color as leads for the medium’s early decades. But it’s definitely a thing that I’m drawn to a lot now. Looking at the ABC family comedies, most of them are telling pretty familiar family sitcom stories, but because it’s filtered through the lens of being African-American, or first-generation Taiwanese-American or whatever, they feel fresh and they feel new and they feel exciting in a way they wouldn’t if it was just another white, WASPY family.

Q: If you were putting together a canon of kids’ TV shows that was not complete in the same way, are there shows that you’ve watched with your kids or on your own that maybe didn’t meet the parameters of the book but that you think count as a canon.

A: If we were doing some sort of kids’ TV canon, we would be getting rid of some of the qualifiers that we put in. “Sesame Street” would be the number-one show I would imagine if we were actually doing some sort of kids’ TV show canon. And we didn’t even consider for this because it’s more of a variety, sketch kind of show as opposed to the narrative fiction we were trying to focus on. There are a bunch like that. “Mister Rogers,” etc.

Q: Is this book something you guys would think about revisiting in five or 10 years?

A: That is our hope. Our hope is that it is successful enough that there will be demand for a second, third, fifth, whatever edition, and we’ll expand the pantheon, and we’ll fold in shows that weren’t eligible then that are now. Maybe “The Good Wife” fits in there, maybe “The Leftovers,” “Recitfy,” maybe some of the other shows that either just ended or are going to end soon will wind up there and other things will move out, and we might do a whole bunch of different shows for “A Certain Regard.” We’re sort of keeping a running tally of things we either didn’t get to, or didn’t do for one reason or another. So certainly, we would like this to be a living document as opposed to a time capsule of our thoughts as of spring of 2016.

Q: I was wondering if you could tell me about how your relationship with Matt has evolved over time, because you guys have such interesting, complementary perspectives. I know I’ve learned a lot about visual storytelling from him, and from the bone-deep fundamentals of television from you. We’ve seen television do a lot of narratively ambitious things, and the structure of the form has changed a little bit. But it’s also become much more visually ambitious and a destination for directors who want to do visually ambitious things. So how has your conversation evolved over time?

A: It’s always been a very good one. It certainly could have been a bad one. Matt was the hot young talent who was brought in to the Star-Ledger after he’d been a Pulitzer finalist. And they were grooming him for big, big things, and, I think, knew even when I got there that they wanted him to eventually become the new TV critic. And I was the intern who came in through the side door. And I wound up being put on the TV beat first because they needed a backup to Jerry Krupnick, who was the veteran TV critic at the time. And there could have very easily been a circumstance where he resented me, or I resented him, and we were put together and it was just incredibly awkward. I know of a lot of beat-sharing arrangements that were like that. And it’s never been like that with Matt. … It was really nice to be able to get back together 10 years later to do this and to sort of be in a room together and be arguing about stuff, and for him to be able to roll his eyes at me, or for me to be able to look at him and say “Come on, Matt!”

And we have different perspectives on things, and I think that comes across well in the great debate where we talk about the different things that we ultimately value as critics. Matt, as someone who is also a filmmaker, at times certainly focuses more on the visual aesthetic than I do. I’m more storytelling — and character-focused. But there’s always been this mutual respect that really helps us work through stuff.

Q: I’m obviously a latecomer to all of this both professionally and personally, as you know. I was curious how you think the profession of TV critic has evolved over time. I’m now at The Washington Post, a paper that published Tom Shales for years, and a paper that has a very noble tradition of TV criticism. I’m still a weirdo who writes about a lot of other things, but I feel like I showed up in the profession at a moment when it was evolving a lot and gaining new prestige to a certain extent. I’d be curious as to your historical perspective on the beat.

A: I’ll put it to you this way. It’s been weirdly circular. When I started doing this, TV critics like Shales and everybody else, it was a simple job: You got the first episode of a show, you wrote a review of the show based on that episode on both the content of it and some speculation of what kind of thing it could evolve into. And maybe you would revisit after the season finale, or at the second season premiere or whatever. And then you’d move on to the next thing.

Over time, thanks not only to me, but to Television Without Pity and a lot of other sources, the mood started going towards writing about things not only after they’d aired, but regularly. So I started doing it first with “NYPD Blue” and then with “The Sopranos” and other things. Matt was doing it for the Ledger for a while with every episode of “Deadwood” and those recaps are sadly lost to the vagaries of NJ.com. It’s really frustrating. Eventually that came to be the thing that people expect, the recap, or the episodic review, whatever you want to call it. To the point now where when I write reviews of things before they air, I get people saying “What are you doing? Why are you writing about this thing I haven’t seen yet? Why are you including any details whatsoever?,” and it’s identical to the kind of thing I would have written 20 years ago.

But what I’ve found is because we’re in Peak TV in America and there’s so much stuff, not only is it not realistic to recap every episode of all of the most interesting things, but it’s not a great use of time because what people seem to be screaming for the most is just “Help me decide what to watch, period, and we’ll worry about the episode-to-episode of it when we can.” And so the initial review has sort of rekindled its value the last couple of years in a big, big way.