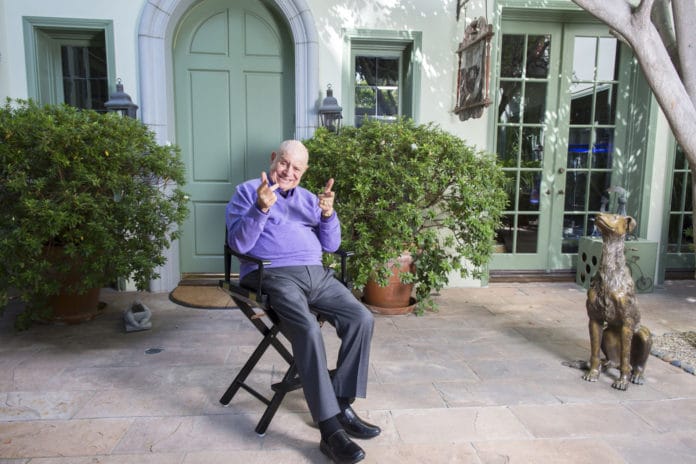

LOS ANGELES — “Sweetie,” Don Rickles says, welcoming us to his sumptuous Spanish villa near Beverly Hills. “Can I get anything for you, dear?”

This is the comedian known as the Merchant of Venom, the Insult King from Queens, Mr. Warmth (as in precisely the opposite). But not once in a convivial afternoon will he lob an insult our way, the sort he hurls at friends and fans alike, the latter paying handsomely for a dose of Rickles ridicule. At one point, he takes our left hand, bows his bullet head and, in the custom of an Old World courtier, bestows a kiss.

It’s one of Hollywood’s worst-kept secrets that Don Rickles is a mensch.

He is beloved by Morgan Freeman, Martin Scorsese, Jack Nicholson, Clint Eastwood. “The kindest man I’ve come into contact with,” Johnny Depp gushed at a star-studded tribute two years ago.

Sinatra adored him. “Frank was the kind of guy, there was no gray area,” says Rickles. “He either loved you or fuggedaboutit.”

Johnny Carson loved him, too – and the late “Tonight Show” host liked almost no one.

“Don talks smack to people,” says Kathy Griffin, another pal. “But he reeks of sweetness.”

On May 8, this much-loved avatar of invective turned 90. His career spans six decades, from appearing in a Clark Gable film to voicing “Toy Story’s” Mr. Potato Head.

His peers? Dead, dead, dead, dead, dead (Buddy Hackett, Alan King, George Carlin, Joan Rivers – even Garry Shandling, who was almost 25 years his junior) or retired (Shecky Greene). Rickles is one of the last of the old-time stand-ups standing.

These days, he’s a sit-down comedian. He’s largely confined to a chair – today it’s a recliner – due to necrotizing fasciitis, a horror show of flesh-eating bacteria that struck in 2013 and six operations later left his left leg bum.

Has it slowed him down? Not so much. He still tours, defying expectations. And he’s more A list than ever, doing Jerry Seinfeld’s “Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee,” attracting Eva Mendes and Ryan Gosling to his L.A. show, hanging with industry swells at Vanity Fair’s molto selective Oscar kissfest, where he held court for seven hours, younger performers – they were all younger – dropping to their knees to pay their respects to the Don.

On this day, he’s ensconced in his second-floor man cave, dubbed the Mr. Warmth Room (says so right on the door) and crammed with memorabilia, a veritable den of Don. There’s his caricature from The Palm, a signed baseball bat from his beloved Dodgers, a stack of “Mr. Warmth” cocktail napkins with his likeness (an earlier likeness, from the comb-over days), a cabinet crammed with his late son Larry’s musician figurine collections, photos of Don and celebrities everywhere, even the bathroom.

His offstage attire is country club gentleman. His voice is a rasp of a whisper. But he can slay without words: His eyebrows are semaphores; his left hand a weapon that can dismiss a subject with a quiver.

Rickles, of course, was politically incorrect before it was incorrect. He elevated rudeness to an art form, but often with an embrace after the sting. He loves his audiences. In return, they love the expectation of the unexpected, the unleashing of what is generally not said.

“Don is saying the things that other people are thinking,” says Bob Newhart, Rickles’ best friend and travel buddy, the sweatered stoic to his sweaty jester. “There’s an expectation of risk when you go and see a Rickles show.”

Newhart should know.

“Such a nice family man,” Ginny Newhart gushed when she met Rickles in Las Vegas in 1968. Uh, wait, Newhart cautioned. That night, at the 2 a.m. show at the Sahara, Rickles gestured toward them: “The stammering idiot from Chicago is in the audience, along with his hooker wife from Bayonne, New Jersey.” The couples, Don and his beloved Barbara (51 years), Bob and Ginny, have been dear friends ever since.

Rickles comes up with all his own material, the best of it ad-libbed and delivered rapid-fire at the front row, the most dangerous place in comedy. Rickles cannot tell a funny story. He doesn’t do jokes, per se. He reacts, free-forming from the stage.

And he can read an audience. “I always said that if I had the education,” he says, “I could have been a damn good psychiatrist, because I can read people pretty good.”

He knows how far he can go and which subjects to avoid. He can get risque, but he never works blue. And, “I don’t get into politics,” he says.

Politics, however, has a way of finding him. At Sinatra’s insistence, he played Ronald Reagan’s second inauguration. He zinged, “Is this too fast, Ronnie?” Reagan howled. During this presidential season, Donald Trump said of Marco Rubio’s swipes, “He decided to go Don Rickles. But Don Rickles has a lot more talent.” Meanwhile, observers detected a dash of Rickles in Trump. In response to which the comedian shrugs and shakes his left hand, as if to say, “Are you kidding?”

—

This is a golden age of comedy, literally. Seinfeld is a near-billionaire. Tina Fey can open a movie, score a production deal, anything she wants. Amy Schumer inked a deal north of $8 million for her memoir.

“In my day, the money was so different,” Rickles says. “How would it have been for them if they had started out when I did?” On the other hand, “I wonder how Amy Schumer is going to be when she’s 90? Look, I’m not starving.”

No, he is not. His home is decorated in overstuffed Town and Country. The bar – what a bar! – is all Versailles mirrors and a wedding registry’s worth of Waterford.

He has worked constantly and appears to have never said no to anything, as if the gigs and the money and the accolades from other comics might dry up by Tuesday. He worked seemingly every television series in the history of the medium (“Gilligan’s Island,” “F Troop,” “Beverly Hillbillies”), the Bikini Beach movies and most talk shows, skewering hosts and guests.

He was a staple of the televised Dean Martin Celebrity Roast, a fog of Scotch and Kent cigarettes from 1974 to 1984.

“I was the big macher,” he says, the man who made the event happen. “I was the closer.” No one wanted to follow him after he expectorated barbs.

Rickles grew up in Queens and spent more than two years in the Navy during World War II – an experience that remains a staple of his act. Afterward, he dreamed of being Jason Robards, the Eugene O’Neill virtuoso and his classmate at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, along with Anne Bancroft and Grace Kelly.

Instead, he mastered the long night’s journey into day.

He played strip clubs. He got fired from strip clubs. “For years I was known as ‘Charlie Rejection.’ The managers didn’t get it.”

If he never reaped today’s fortunes, he enjoyed the Rat Pack experiences that younger comics might kill for, the beginning days of Las Vegas when, as he recalls, “past the Sands, there was nothing but a lot of sand.”

Rickles played three performances a night – midnight, 2 a.m. and, brutally, 5 a.m., “to keep the guys at the tables” in the lounge at the Sahara, the lesser room.

“At 5 a.m., you get all the guys who lost money,” Rickles says. “I always perspired because I was nervous. I used to get soaking wet. I’d go through tuxes.”

But he loved it. “You had a hardcore audience, that’s what the biggest attraction was. I controlled all of them,” he says. He heckled the hecklers. “The rowdy guys snapped to attention and listened to me.” Eventually, he played the big room.

In his show, Rickles pays tribute to his mother, Etta, who died in 1984. He calls her “the Jewish Patton.” “I was Momma’s little boy,” he says. “She had a good business head. She was very critical. And she was very forceful. All actors are shy when they’re kids. I was. She got me to talk up. She gave me courage.” Although she used to ask, “Why can’t you be more like Alan King?”

Rickles married at 38, ancient for those days. (Etta moved in next door.) For years, he had dated women who were distinctly not wife material, the sort who worked the edges of the Vegas night. Then he met Barbara, his agent’s secretary. They had two children: Mindy, who does stand-up, and Larry, who won an Emmy with his father for the 2008 HBO movie, “Mr. Warmth: The Don Rickles Special.”

In 2011, Larry died of pneumonia at age 41. “Horrible,” Rickles says, his voice tapering off. More he cannot say. Larry’s 10-year-old French bulldog, Chauncey, lives with him and Barbara, the likeness between comedian and hound lost on no one.

—

Rickles’s big birthday came and went, a cake, dinner with the Newharts at Mr. Chow’s in Beverly Hills, two singers hired by conductor Zubin Mehta singing “Happy Birthday.”

Four days later, he played The Sands in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, an antiseptic box behind the rusting hulk of a steel mill. Not exactly Vegas, but he’ll take it.

He works like no other comic, backed by a 14-piece band. He performs in a tux and an oversized floppy bow tie, circa 1976.

Some of the humor is vintage. He jokes about Jimmy Cagney, dead for three decades, something about a dentist who was a relative and old New York. It’s his shtick, he’s in no rush to change the formula.

A fan howls from mid-floor: “Don, I want to shake your hand!”

Rickles snaps: “Get better seats.”

In the front row, he finds his prey.

“You’re 92?” Pause. “I’m not going to lie to you. You look it.”

Sure, he can’t pace the stage the way he used to, but that trumpet of a mouth still works fine.

He gives little thought to stopping. “As long as I can get on a stage,” he says, “and they’re laughing their fanny off, and they show up, and I’m well enough – even with the bad leg – I’ll keep working.”

Eight dates brighten his tour schedule, plus an appearance on “The Tonight Show,” another turn as Mr. Potato Head in “Toy Story 4.”

Three standing ovations in Bethlehem. Don Rickles is eager for more.