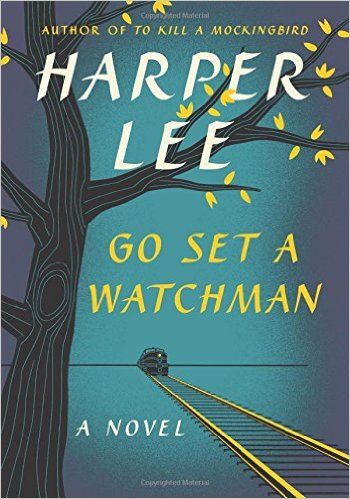

It’s been fascinating, if a bit depressing, to watch the backlash build against Harper Lee’s newly discovered novel “Go Set a Watchman,” which went on sale Tuesday. Now that Atticus Finch turns out to harbor racist views, fans of “To Kill a Mockingbird” have taken to social media in large numbers to announce that they will boycott the book. Some even insist that Lee could not possibly have written it.

They don’t know what they’re missing.

“Go Set a Watchman” offers a rich and complex story, in many ways more textured than “Mockingbird.” To make the novel about pinning the right label on Atticus is to miss the point. “Watchman” isn’t mainly about race. It’s about the process through which protagonist Jean Louise Finch comes to grips with the realization that the father she has worshiped for decades is fallible. The story wouldn’t be interesting if his failings were smaller.

In “Mockingbird,” set during the Depression, Jean Louise was 8 years old. Now she’s 26, it’s the mid-1950s, and she lives in New York City, a place she partly despises for its confident and ignorant judgments about others — including Southerners. Alas, when Jean Louise returns to her hometown of Maycomb, Alabama, for a vacation, she finds that those she grew up with aren’t worthy of the pedestals on which they stand in her rosy memories.

But in her haughty dismissal of the townspeople, she evinces what her Uncle Jack identifies as her own bigotry, in the word’s classic sense: an inability to empathize with people whose views differ from her own. The story centers on Jean Louise’s effort to come to terms not just with the shortcomings of others but also with those that she finds in herself. If there’s a message for the rest of us in “Watchman,” it’s found in that struggle.

Oh, there is race in the tale, and lots of it. Critics have focused on what seems to them a new Atticus (more on that in a moment), but the book’s most racially charged scene — as well as its most poignant and painful — comes when Jean Louise visits Calpurnia, the beloved maid of “Mockingbird.” Jean Louise tries to offer condolences because Calpurnia’s grandson has been arrested for running over a white man with his car. Expecting a return of affection, she discovers to her dismay that the now- aged Calpurnia sees the young woman she raised the same way she sees everyone white: an outsider, a dangerous presence in her home, someone you’re respectful to only because you have no choice. Calpurnia even dumbs down her speech. (Readers of the original may recall that her English is often excellent: She learned to read by studying Blackstone’s “Commentaries.”) When Jean Louise asks whether Calpurnia ever loved her and her brother, she is met with a stony silence.

Then there is Maycomb itself. Jean Louise is anguished to learn that the community was built upon a racism to which she as a child was hardly exposed. Suddenly prejudice is not the sole property of poor whites — the Ewells from “Mockingbird,” for instance. In the wake of fears of social upheaval sparked by the early years of the civil-rights movement, the N-word is on everyone’s lips. Jean Louise’s memory has played her false. She never knew the town at all.

And what of Atticus, the hero of the first novel? Readers loved him for his passionate defense of Tom Robinson, the black man falsely accused of raping a white woman — a defense Atticus undertook at considerable personal cost in the very teeth of the encompassing ideology of Jim Crow. But nothing in that defense is inconsistent with the character we discover in the new tale.

Early in “Watchman,” Atticus agrees with his daughter that the failure to obtain a conviction in “that Mississippi business” — a veiled reference to the Emmett Till case — was the South’s “worst blunder since Pickett’s Charge.” When we learn that Atticus was in the Ku Klux Klan, Uncle Jack assures Jean Louise that her father would nevertheless hurry to the defense of anyone the Klan threatened with physical violence. Her sometime boyfriend, Henry Clinton, tries to explain Atticus’s involvement as necessary for getting things done — and for keeping a close eye on what his neighbors are doing.

Such rationalizations will hardly persuade the modern reader, and shouldn’t. Nevertheless, they echo the justifications offered for Hugo Black’s membership in the Klan before he became one of the Supreme Court’s great civil libertarians — justifications with which Lee, growing up in Black’s home state of Alabama, would surely have been familiar.

I’m not trying to defend Atticus — or, for that matter, Jean Louise, who plainly shares a lot of her father’s objectionable views. The two of them agree, for instance, that the Supreme Court’s school desegregation decisions are rushing things, trying to impose a timetable when “the Negroes” aren’t ready for full participation in government. But here we perhaps ought to recall the historian Gordon Wood’s admonition not to judge the past by the standards of the present. For Atticus’s place and time, in the Alabama lowlands of the 1950s, such a view by a white Southerner would have been considered rather liberal. And not a few great Northern liberals of the era viewed black people in pretty much the same way. Racism is rarely as simple as we want it to be.

More to the point, as we soon become aware, Jean Louise isn’t angry at Atticus because of his beliefs. She is angry because he hid them from her. She’s furious that Atticus turns out not to be the man she thought he was — the same reason, surely, for the fury of many of those who loved “Mockingbird.” If only Atticus had been less perfect when she was growing up, Jean Louise tells herself, she might have been able to forgive him for hiding the truths she so painfully learns.

We want our heroes and villains simple — either all good or all bad. But sorting the world into angels and demons is what keeps us from acknowledging the complexity that makes life both valuable and difficult. People we admire can harbor terrible views. We are always free to decide that those with whom we disagree are beneath us, and often that’s just what we do. In “Go Set a Watchman,” Harper Lee invites us instead to be adult enough to accept that nobody is all one thing.

— Stephen Carter is a Bloomberg View columnist and a law professor at Yale.