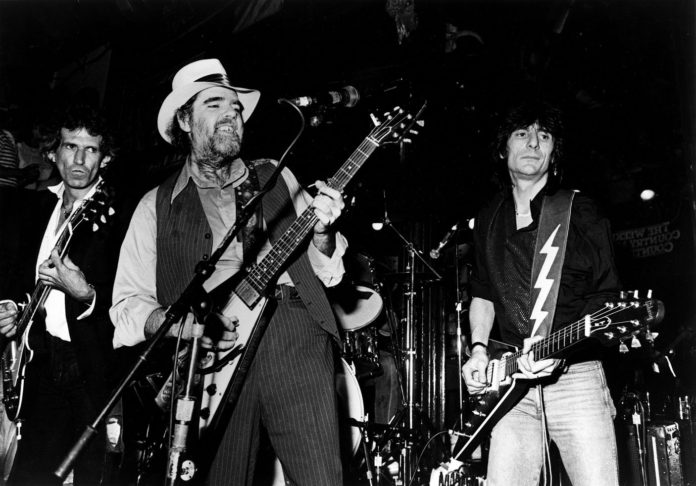

Lonnie Mack, a guitarist and singer whose early 1960s instrumental hits “Memphis” and “Wham!” influenced a generation of guitarists and whose singular mix of blues, country and gospel inspired performers such as Keith Richards, Stevie Ray Vaughan, the Allman Brothers Band and Danny Gatton, died April 21 in Nashville. He was 74.

Alligator Records announced the death but did not disclose the cause. Mack lived in Smithville, Tennessee.

“Memphis,” an instrumental variation on Chuck Berry’s “Memphis, Tenn.,” and Mack’s follow-up, “Wham,” cut through the predictability of 1963 Top 40 radio, where teen idols and reverb-drenched surf instrumentals ruled. Mack’s guitar work combined the harsh attack of urban blues with the frenetic tempos of rock ‘n’ roll.

His guitar – an arrow-shaped 1958 Gibson Flying V – was as distinctive as his playing style: chords that rang with an organ-like sustain, courtesy of his Magnatone amp, followed by a barrage of trebly, staccato notes during his solos.

“Lonnie Mack was one of the first white guys to really make a mark playing blues-infused guitar,” said record producer and blues historian Dick Shurman. “I think of him as a prototype of what later could be called Southern rock. His music was a blend – it wasn’t a conscious blend – he brought black and white styles together seamlessly.”

Although his instrumentals sold in great numbers, Mack struggled to find chart success with his impassioned late 1960s ballads such as “Why,” “I’ll Keep You Happy” and “Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way.”

Mr. Mack was one of the first “blue-eyed soul” singers whose records were promoted as rhythm-and-blues. He recalled going to a soul radio station in Birmingham, Alabama, for an interview when “Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way” was beginning to break out. The disc jockey stopped playing it when he discovered Mack was white.

But others were taken with Mack’s soulful style.

Rock critic Greil Marcus said of “Why,” which climaxes with a full-throated scream in its last verse, “This tune offers a false choice: listening to the most stately ballad in the annals of white blues, or listening to a man kill himself. The choice is false because in the last verse, you don’t get to choose.”

In between the gigs, he did session guitar work behind James Brown, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters and blues guitarist Freddie King. He later filled in as a session bassist for The Doors on the songs “Roadhouse Blues” and “Maggie M’Gill.”

Mack moved to California in 1968 when he signed with Elektra Records. The company also hired him to scout for talent, but he came to loathe the job after Elektra failed to sign singer-songwriter Carole King at his suggestion. Mack, who was known for a quick temper – he once shot his computer with a gun – was also viewed by record company executives as difficult.

“His temperament wasn’t suited to stardom,” Shurman said. “I think he’d rather have been hunting and fishing. He didn’t like cities or the business.”

By the late 1970s, he had returned to playing local jobs in Indiana and Ohio. In 1985, Vaughan persuaded Mack to move to Austin, where he signed with Chicago-based blues label Alligator and recorded “Strike Like Lightnin’,” with a guest appearance from Vaughan. That same year, he performed at Carnegie Hall for the concert DVD “Further On Up the Road,” with fellow guitarists Albert Collins and Roy Buchanan.

Lonnie McIntosh was born in West Harrison, Indiana, on July 18, 1941. His father, a farmhand, played banjo, and Mack began performing guitar in the family bluegrass band at 7.

“Didn’t have a record player or nothin’,” he told Dan Forte in Guitar Player magazine. “Most of the places we lived didn’t have electricity, so that made it rather difficult. … We used to have a whole lot of jam sessions with the family in the old days.”

Mack quit school in the sixth grade after fighting with a teacher and soon began professional music engagements in local clubs, eventually changing his last name to Mack. In his teens, he recorded with rockabilly and country bands for small Ohio labels.

He reportedly was married and divorced three times. Survivors include five children; two sisters; a brother; eight grandchildren; and seven great-grandchildren.

Discussing his career, Mack told writer Sean McDevitt in 2007: “I ain’t got no regrets, but at the same time, it ain’t something I would recommend to a young kid right now like I used to. … The only way you can make any money is to do what everybody’s telling me I need to go do: Go back out and tour and get the money at the door.”

He added, “I mean, you’d better love it. I mean, daggone! Why I got into it in the first place wasn’t about the money. I got into it because I loved it.”