WASHINGTON — The 150th anniversary of the start of one of the nation’s greatest manhunts began Tuesday at 10:15 p.m.

That’s about when John Wilkes Booth dropped his smoking Derringer in the box where Abraham Lincoln slumped mortally wounded, leaped to the stage of Ford’s Theatre, staggered out the back door, grabbed the reins of his horse from an unwitting Ford’s employee named Peanut John, and took off.

Twelve days later and about 100 miles away, Booth would fatally shot by federal troops in Richard Garrett’s burning tobacco shed, a few miles south of Port Royal, Virginia.

As part of their investigation, federal troops and detectives traced Booth’s route in reverse, to figure out where he stayed, who helped him, and who could provide witness testimony. Ever since, historians, enthusiasts and tourists have tracked the assassin’s footsteps. The point isn’t to salute Booth, it’s to revel in the amazing fact that so much history gleams through cracks in the 21st century landscape.

The Washington region has produced numerous experts on the minute-by-minute tick-tock of Booth’s desperate flight, including James Swanson (author of “Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer”), Michael Kauffman (“American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies”) and James O. Hall (“On the Way to Garrett’s Barn — John Wilkes Booth & David E. Herold in the Northern Neck of Virginia, April 22-26, 1865″). Hall, too, was one of the first to lead organized bus tours of the route 40 years ago.

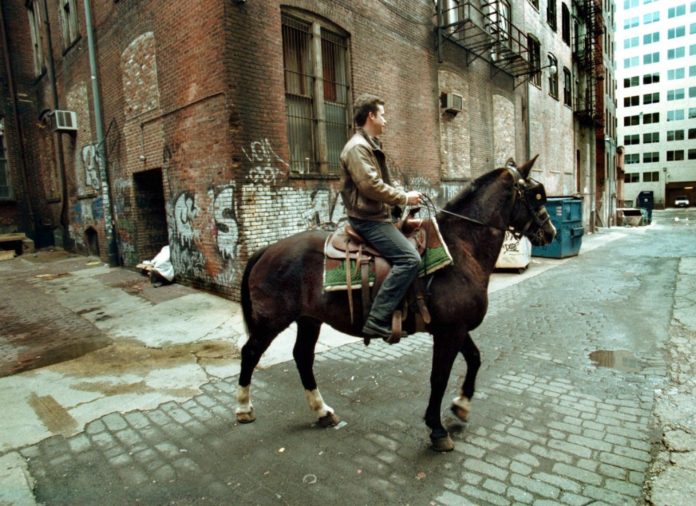

Then there’s me, no expert, just curious. A number of years ago, my editor Tom Shroder asked cryptically: “Do you ride?” We cooked up an elaborate plan to re-experience the assassin’s flight on the 134th anniversary. The goal was to achieve as much obsessive authenticity as possible. I leaped to the stage of Ford’s from a ladder. Rode a horse through downtown Washington to Maryland. Rowed a boat against the tide of the Potomac River, while carrying a burning candle and a compass, as Booth did.

This was not long before the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. I don’t think it’s possible anymore to trot by the Capitol on a steed, or interview from the saddle a random member of Congress pumping gas on Pennsylvania Avenue SE.

The physical challenge turned out to be too much, and I didn’t even have a broken leg. At the Maryland line, I switched to a Ford Mustang (get the horse reference?). On the Potomac, after 90 minutes pulling against the tide, a Washington Post outdoors columnist gave me a tow to Virginia with his motor boat.

I traveled much of the way with Kauffman, who knew all the stops, most of which have historical markers. We went into the Surratt House Museum, Mary Surratt’s former tavern, where Booth received a carbine that had been hidden for him. We stopped at the Dr. Mudd House Museum, where Samuel Mudd set Booth’s broken leg. We ate ham sandwiches in the pine thicket outside the little town of Bel Alton, where a Confederate agent brought Booth bread, ham and newspapers. There, Booth read press accounts of his deed. The actor was shattered to see himself cast as a villain, not a hero who slew a tyrant. He wrote agonized diary entries:

“I struck boldly, and not as the papers say. … The country is not what it was. This forced union is not what I have loved.”

Another entry, later during his flight, shows the awful truth beginning to pierce his delusions:

“For my country I have given up all that makes life sweet and Holy, brought misery upon my family, and am sure there is no pardon for me in the heavens, since man condemns me so.”

Along the way for Booth trackers, channels to the past are everywhere. In Virginia, I interviewed folks living in houses where Booth stopped on his flight. They were all caught up in the timeless drama.

Nowadays, tours of the escape route are more popular than ever. Four 12-hour bus tours this month organized by the Surratt House Museum for a total of 200 people sold out in January. The museum, which is part of the Prince George’s (Maryland) County Department of Parks and Recreation, also organizes special tours for groups of 30 or more. A group of 30 lawyers from the Frederick, Maryland, area recently made the trek, said Laurie Verge, director of the museum.

Four more tours are scheduled for September. To get on one of those, call ( 301.868.1121) or email (Laurie.Verge@pgparks.com) the museum to provide your mailing address, or mail in this form. You will be placed on a list. In June, the museum will mail registration forms to all those on the list. The first 200 who return the forms with payment will get tickets. The cost is $85. Proceeds go toward preservation of the museum.

“Act as soon as you get the letter,” Verge advises. “The tours fill practically overnight, or usually within a week.”

A tour with the Smithsonian Associates April 26 is also sold out, but the website says people can call to be put on a waiting list, or to be alerted if new tours are added.

It’s also fairly easy to make your way on your own. For directions, you can consult the works of those experts on the assassin trail, and see the large on-line literature as well.

The last stop is hard to visit. Garrett’s house and tobacco shed are long gone, except for scarce ruins. The house was located on land that is now on the median strip of Route 301 where it cuts through Fort A.P. Hill. The shed was on land off the right shoulder of the southbound lanes. Access to the land has been blocked.

A historical sign to mark the site went missing last fall. Virginia authorities could not immediately come up with funds to replace it, so the Surratt Society (based in Maryland!) raised $1,700 to replace the marker, according to Verge. It will be dedicated at a small ceremony at the Port Royal Museum at 2 p.m. Sunday, April 26.

After being carried to the Garrett house porch, as he lay paralyzed and dying, Booth reportedly muttered his last words: “Useless, useless.”

Here’s the route I took:

Tracing Booth’s Route

By Horse: From the alley behind Ford’s Theatre, turn right on F Street NW, right on 5th Street NW, left on E Street NW, right on New Jersey Avenue NW, left on Constitution Avenue NW, right on First Street NE, left on Independence Avenue SE, right on Pennsylvania SE, right on 8th Street SE, left on M Street SE.

By Horse Trailer: Cross 11th Street Bridge

By Horse: Continue up Good Hope Road to Alabama Avenue SE

By Mustang: Take Naylor Road to Route 5. Cross Beltway, exit onto Linda Lane, continue on Old Branch Avenue to the Surratt House Museum. Continue on the same route now called Brandywine Road. Right on Horsehead Road, right on Poplar Hill Road, left on Dr. Samuel Mudd Rd. to the Dr. Mudd House Museum.

Continue on Mudd Road, right on Bryantown Road, left on Route 5, right on Burnt Store Road, which becomes Olivers Shop Road, right on Route 6 across Zekiah Swamp. Left on Bel Alton Newtown Road. Left on Wills Road to the Pine Thicket where Booth hid (across railroad tracks on private property). Return on Wills Road. Left on Bel Alton Newtown Road. Left on Route 301. Right on Popes Creek Road to what is now the Loyola Retreat House, private property, where Booth boarded a rowboat.

By Rowboat: Booth was blown upstream his first attempt, but we try to go straight across. Fighting strong tide, we resort to a motorboat tow. By Motorboat, continue to Dahlgren Marine Works, on land formerly owned by Confederate spy Elizabeth Quesenberry.

Back in Mustang. Take Route 206 to Cleydael subdivision, where Booth stopped for help. Continue on Rt. 206., left on Rout 611, right on Rout 301 to the site of Richard Garrett’s tobacco shed, where Booth is fatally shot, about 2.5 miles south of Port Royal, on the right shoulder of the southbound lanes. He died on the porch of the main house, which stood where the highway median is now. To make the site easier to find, a new historical marker will be dedicated April 26. However, access to the land is blocked.