NEW YORK — “Dude, I have no answers.”

It could be construed as a dodge, but coming from Ezra Edelman it’s more like a declaration of purpose.

Not only did the D.C.-raised filmmaker have the audacity to make an 7 1/2-hour documentary about one of the most warmed-over subjects in recent American history, he’s won a parade of critical acclaim. New York Magazine called it a “masterpiece,” while Hank Stuever’s Washington Post review called it “nothing short of a towering achievement.” And that’s without peddling any flashy new revelations. “That’s not what I’m interested in,” he said over tacos near his home in the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn. “I’m doing something a little different.”

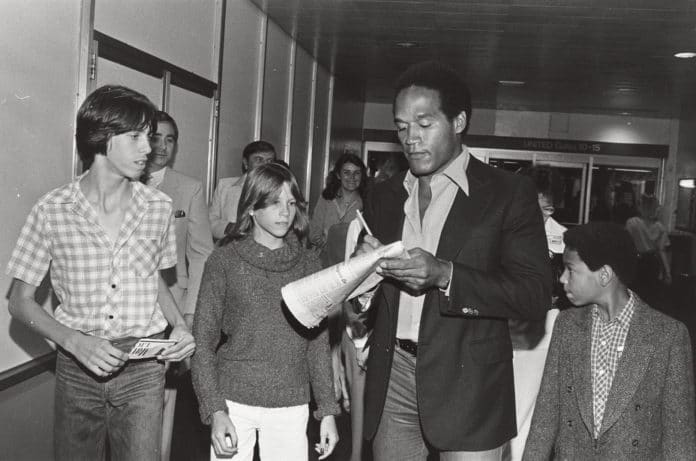

What Edelman does instead with “O.J.: Made in America,” a heady, five-part, half-century-spanning epic that debuts Saturday on ABC before shifting to ESPN, is posit the story of O.J Simpson as a Rorschach test for the American psyche. Hero or villain, creator or creation, denier or exemplar of his race, how we view O.J. says as much about ourselves as it does the enigma currently languishing in a Nevada prison. Unlike the recent FX miniseries, “The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story,” which tightly focused on Simpson’s murder trial, Edelman’s documentary starts three decades earlier, when the charismatic, prodigiously talented running back began isolating himself from the expectations and concerns of his race.

As Edelman explained, “What I understood from the get-go was the juxtaposition between 1967 O.J. – a black kid two years removed from growing up in public housing in San Francisco – arriving at this lily-white conservative place with a lot of wealthy students [USC], which is literally next door to this other place that, a year and a half before, burned because of the dynamics between the police and black citizens in L.A. And from there O.J. pursues a path that completely ignores the plight of said people – until that gets completely turned on its head when we get to the trial. And you’re like, that’s the story.”

—

Edelman’s own narrative would seem to have prepared him well for exploring the O.J. phenomenon. Now 41, he grew up in Cleveland Park, the mixed-race son of renowned civil rights activist Marian Wright Edelman, founder of the Children’s Defense Fund, and Peter B. Edelman, a Georgetown law professor who notoriously resigned from his position as assistant secretary of health and human services in the Clinton administration over welfare reform.

Before studying history at Yale University, he attended the Quaker school Sidwell Friends, and recalled a meeting for worship in which “our little bubble” was burst by anger over the Rodney King beating (an incident that looms large in the O.J. narrative). Edelman recalls the incident as evidence of how sheltered he was from that reality.

Yet what initially attracted him to this project wasn’t the charged subject matter, but rather the prospect of working in an uncommon length. “That initial conceit for the canvas – that’s what got me,” he said. “Telling one story over that period of time is a challenge to me regardless of whether I’m making a film about O.J. or making a film about the restaurant we’re sitting in.”

After college, he was researcher for CBS’s 1998 Winter Olympics broadcast, and eventually directed sports documentaries, including HBO’s Peabody Award-winning “Magic & Bird: A Courtship of Rivals,” and “The Curious Case of Curt Flood,” about the center fielder whose 1970 lawsuit over being traded eventually reached the Supreme Court. Each considers the racial and social tensions present in athletes’ exploits.

“He’s so thoughtful about the subject of race, not in ways that overwhelm the narrative, but in ways that really challenge you to think about what you’re seeing,” said Connor Schell, executive producer of “O.J.”

“You learn pretty quickly when dealing with Ezra that you can’t casually say things to him that you haven’t entirely thought through yourself. Because everything you’ve thought about, he’s thought about,” he added.

—

Edelman was drawn to sports from a young age, and was a rabid fan of the Georgetown basketball team. Since his father taught in the law school, he’d hang out at Yates Field House and play video games. “I remember sitting down to play Galaga, and there was this dude who sat across from me and said, ‘Can I play with you?’ And it was Patrick Ewing,” he said. “I’m like, 8, and he’s seven feet tall, and I’m like okay.” The fact that this was an all-black team, coached by an outspoken black coach at a largely white school, is something he would later explore in “Requiem for the Big East,” but these reasons weren’t what made him care about the Hoyas as a kid. “To me, it was, that’s the local team, and they kick a–,” he said.

The youngest of three boys, Edelman was the only son not to pursue a career in what his brother referred to as “the family business.” Reached by phone in Oregon, Jonah Edelman, co-founder and CEO of public education advocacy group Stand for Children (eldest brother Joshua is an educational administrator), described Ezra as an introvert from the start, and marveled at his establishing a career in the arts despite coming from a family “I wouldn’t describe as creative in the least bit,” he said, laughing.

“Ez views himself in some ways as the black sheep of the family – which is comical when you look at his body of accomplishment,” he said. Though their parents – who declined to speak for this story – were supportive of each of their sons’ pursuits, Jonah Edelman said the bar had been set extremely high. “A lot of it is just that existential weight you feel when you grew up in a family where your mom is a civil rights leader that worked for Dr. King and your dad worked for Robert Kennedy, and they’ve both had these illustrious careers working on social issues.”

—

Back in the restaurant, Ezra Edelman described the complications of going his own way. “It’s like, is this okay? Is there a worthiness to these pursuits that I’ve dedicated my time to? A lot of it is self-driven. It’s very internalized. And it took me some years to feel better about that,” he said.

The irony is that Edelman is speaking as someone who’s now made a major contribution to the dialogue about race and celebrity in America. “It’s interesting arriving at a place where you gain some traction in what you’re doing, and you wonder if that validates the path that you chose,” he said.

He winds the conversation back to O.J., and to the cultural irresolution that continues to preoccupy him. “What are all of these things that went into why everyone lost their minds?” he said. “I have questions about what must have been going on in O.J.’s mind for the last 20 years, but I can’t access those things more than I can show you. Just look and think for yourself.”

http://espn.go.com/30for30/ojsimpsonmadeinamerica/