This program airs at 8 p.m. CT tonight on KERA in the Dallas/Fort Worth area.

www.kera.org

They were a busy couple in their 30s, a Unitarian minister and a social worker, with a 2-year-old daughter, a 7-year-old son and plenty of duties in their congregation. In January 1939, the Rev. Waitstill Sharp and his wife, Martha, could have turned down the request from a senior leader of their faith to leave their children and home in Wellesley, Massachusetts, and head to Prague to aid persecuted people in a country on the brink of Nazi takeover.

Seventeen others had declined the mission. But the Sharps said yes.

Their willingness to confront the Nazis, first in Czechoslovakia and a year later on a second mission to France, set an example of humanitarian outreach for an isolationist America not yet at war and reluctant to open its doors to refugees. Working with various aid networks, the Sharps rescued an estimated 125 people – Jews, political dissidents and others under threat as fascist armies spread across Europe. They also helped get food and other assistance to hundreds more in urgent need.

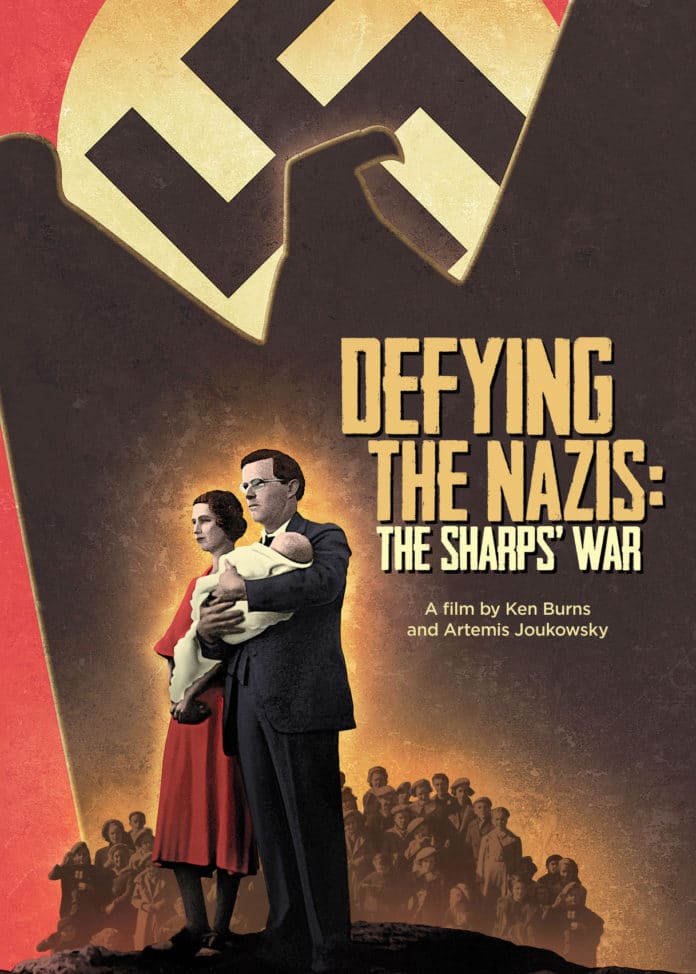

These exploits are recounted in a new documentary co-directed by Ken Burns and the Sharps’ grandson Artemis Joukowsky, with Tom Hanks providing the voice of Waitstill and Marina Goldman the voice of Martha. “Defying the Nazis: The Sharps’ War,” airing Tuesday evening on PBS, portrays the courage and sacrifice of an ordinary couple caught in extraordinary times. The story takes place more than 75 years ago, but the questions it poses seem timely now.

“The Sharps are the better angels of America,” said Deputy Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken last week at a White House screening for scholars, diplomats, Holocaust survivors and other dignitaries. (The Obamas did not attend.) The film, Blinken said, humanizes relief work at a time when the world needs to do far more to aid refugees from war-torn Syria and elsewhere.

That screening and another at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum brought together numerous relatives of the Sharps – including me, a cousin of Waitstill’s through a maternal great-grandmother – and individuals whom the couple helped rescue.

Alex Strasser, 82, a doctor from Rochester, New York, was 6 years old when he and his 8-year-old brother, Joseph, boarded a ship to the United States after Martha Sharp wrangled permission for them to leave from French authorities in Vichy. Strasser declared it “wonderful” and “amazing” to see the film spotlighted in the nation’s capital.

“The world should know,” he said, that the refugees simply wanted “to escape persecution and to start a new life. We became Americans.”

—

The Sharps’ saga plunges rapidly from the tranquility of New England to chaos and suspense in Europe.

Sometimes the couple took major risks, providing currency exchange on the black market or smuggling targeted individuals across borders. One night in March 1939, just after the German occupation of Prague, Martha Sharp escorted a hunted man she called “Mr. X” through the city streets, dodging the Gestapo, to deliver him to the British Embassy.

In September 1940, Waitstill Sharp shepherded the German Jewish author Lion Feuchtwanger, a renowned anti-Nazi, and others on a clandestine journey from Marseille to Lisbon. The minister and the novelist hopped off one train to elude authorities, and Feuchtwanger crossed into Spain on foot via mountain paths. On a ship to the United States, Feuchtwanger asked Sharp why he did what he did.

“I’m not a saint,” Sharp replied, according to a book that Joukowsky wrote to go with the film. “I’m capable of any of the many sins of human nature. But I believe the will of God is to be interpreted by the liberty of the human spirit.”

“You get enough reward out of that?” Feuchtwanger asked.

“Yes, I do,” Sharp said.

The Sharps proved expert navigators of international bureaucracy, securing coveted visas and departure tickets, including transatlantic passage for 27 imperiled children. They often worked apart, traveling solo to one city or another on the increasingly hazardous continent in a race to save lives.

“They had moral imagination,” said Sara J. Bloomfield, the Holocaust Museum’s director. “They could imagine the human capacity for evil, and they could imagine the possibilities for action.”

—

For their efforts, the Sharps are two of five Americans honored at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust remembrance center in Israel, as “Righteous Among the Nations.” The title is reserved for non-Jews who risked life or liberty to save persecuted Jews.

A couple of years ago, my wife took one of our daughters to see Waitstill’s and Martha’s names engraved on the walls of the Garden of the Righteous in Jerusalem. In recent years, we cousins have marveled to learn through the extended-family grapevine about the Sharps, an unexpected revelation of our shared link to two admirable figures from a perilous era.

The story might never have emerged but for the persistent curiosity of the Sharps’ grandson. After the war, the couple found that their lives had been reshaped. They divorced in 1954 and afterward rarely spoke about their work in Europe.

“It was almost a secret,” said Joukowsky, of Sherborn, Massachusetts. Both Sharps were by nature modest, he said, and he suspects that they also grieved for the many they were unable to save, including eight Jews who ran their Prague office and died in concentration camps.

Joukowsky got the first inklings of the story in 1976, when he was 14.

That year, a ninth-grade teacher gave him an assignment: Interview someone who had shown moral courage. He asked his mom for suggestions. “She said: ‘Why don’t you talk to your grandmother? She did some cool things during World War II,’ ” recalled Joukowsky, 55. “Little did I know.”

Joukowsky’s mother, also named Martha, was the Sharps’ daughter. Conversations with his grandmother led to a great history paper – “The only ‘A’ I ever got,” Joukowsky said – and whetted his appetite to learn more.

It took many years. Waitstill died in 1984, and Martha in 1999. Each left behind oral histories and unpublished manuscripts. But the wider world knew very little about the couple’s service in Europe. Nor did the Sharps’ extended family. My aunts and uncles can’t recall ever hearing any tales in childhood about their Holocaust-fighting kin.

—

For Joukowsky, a breakthrough came after his grandmother’s death. He discovered a trove of documents in her basement – letters, photos, hotel bills, ticket stubs and more. The papers included hundreds of names of people the Sharps had sought to help. Using these sources and consulting with the Holocaust Museum and other experts, Joukowsky and his research team, including private detectives, tracked down dozens of people who knew something of the tale.

Interviews with witnesses, including his mother and her brother, Hastings (who died in 2012), became the genesis of the film. The years-long project reached a milestone when Yad Vashem bestowed the posthumous honor on his grandparents in 2006. “Suddenly we had validation from the most important Holocaust agency in the world,” Joukowsky said.

Word of the Sharps spread, and Joukowsky circulated versions of his film in churches and synagogues. He also sought advice from Burns, the famed documentarian and a fellow graduate of Hampshire College.

“Three years ago he sent me a rough cut,” Burns said at the White House. “It was a good story. It was a hell of a good story.” Burns decided to team with Joukowsky and roped in megastar Hanks, guaranteeing wide exposure. But Burns deflects credit. “This is, in every sense of the word, Artemis’ film,” he said.

Joukowsky’s family turned out in force for the Sept. 12 screenings: his parents, his four daughters, ages 17 to 29, and an array of other relatives. For we cousins, it was moving to meet the Sharps’ daughter, grandson and great-granddaughters in person here in Washington, bringing the story even closer to home. Joukowsky was all smiles and hugs as he, too, relished the moment of film and family.

The Sharps will also be featured in a planned 2018 exhibit at the museum on the American response to the Holocaust. Daniel Greene, curator of that show, said that significant aid networks sprang not only from the Unitarians but also from groups such as the YMCA and the Quakers. The Sharps were rare but not solitary U.S. activists.

“The question that hangs so heavily over this history is, ‘Why did they do this?’ ” Greene said. “Why did they feel it was their obligation, or their responsibility, to take these risks, when it’s so much easier not to act?

“It’s a great question to ask, and a really hard one to answer.”