In many rock ‘n’ roll bands, bass players are, more or less, lumps.

Some might be half of incredible rhythm sections (John Paul Jones of Led Zeppelin), or great singers (Jack Bruce of Cream), or incredible songwriters in their own right (Sir Paul McCartney). But those who play that four-string thang must face it: Bass players often stand in the back playing the root or the fifth and, particularly in recordings from the first three quarters of the 20th century, are pretty hard to hear.

Hey: The White Stripes, among many others, didn’t even need one.

But one of the artists who helped redefine the bass for a generation of players and listeners — Chris Squire of Yes, who died Saturday of acute erythroid leukemia — thought differently. As much or more than any other bass great — Larry Graham, Bootsy Collins, Mike Watt, Flea, Les Claypool — Squire took an instrument with limited expression that’s difficult to make stand out from the back to the front.

“I couldn’t get session work because most musicians hated my style,” he said. “They wanted me to play something a lot more basic. We started Yes as a vehicle to develop everyone’s individual styles.”

Do not be mistaken: The individual, un-basic bass style Squire created is loathed by many. Yes has been called self-indulgent, pompous and boring — a band more focused on its own members’ virtuosity than artistic expression. Many say no to the 47-year career of these progressive rock progenitors, a group Squire co-founded and played in through many lineup changes.

“Despite the fact that a formidable portion of the music we love (anyone from Radiohead and Super Furry Animals to Hella) is directly influenced by Yes and their prog-rock peers, we tend to look at the early ’70s through punk’s distorting lens,” Pitchfork wrote in 2004, “and that lens shows us images of dinosaur muso wankers lumbering from stadium to stadium with comically oversized light shows and Victorian clothing.”

But Squire said that Yes wasn’t just about showing off.

“I think most artists that have been involved in prog have generally been more clever players than is necessary to be in a lot of rock ‘n’ roll, which is all about feel,” he said. “We in Yes have always developed our interest in that as well, to promote the feel side of music as well as the musicality.”

Born in 1948 in London, Squire, a fallen choirboy, seemed destined for a life of musicality — and rock ‘n’ roll rebellion — from a young age.

“In 1964, Chris was suspended from Haberdasher Aske’s public school (a private school, in Britain) for wearing his hair much longer than was allowed,” Squire’s website read. “The money given to Chris for a haircut was ‘spent on other things.’ Chris never returned to school.”

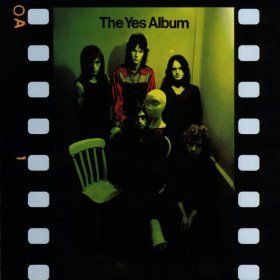

Just four years later, he helped found Yes. In 1971, on its third album, the group scored an international hit with “I’ve Seen All Good People.” Though “I’ve Seen All Good People” weighed in at 6:56, its great length proved a mere preview of coming attractions. Next came “Roundabout.”

“The 11-minute opus that closes Yes’ 1971 album, ‘Fragile,’ begins with an urgency and chaos of frenetically blended guitar and bass notes that lead into a gentle coo of rolling, rhythmic waves,” Tessa Jeffers wrote in Premier Guitar last year. “With a flick of a wrist, maestro Chris Squire breaks the soft groove with his unusual lead bass guitar, punctuating everything with intensely building lines and a haunting melodic immediacy. The two musical ideas furiously dance until suddenly the former dangerous vibe becomes infectious, and the unpredictable mystique and intrigue of the climb peaks. It’s as if the song is trying to tempt a listener to come along — make the voyage.”

“When I grew up that was a rite of passage to be able to play ‘Roundabout’ and I was never able to play it,” Les Claypool, best known as the bassist and frontman of bass-heavy Primus, said just last month. “I mean I could play it but I wasn’t playing it correctly and I still don’t know the whole thing in its entirety but that’s one my favorite riffs to go to every now and again.”

This was playing even a Republican presidential candidate could love.

“Yes’ bass player is one of best of all time and was a huge influence on why I wanted to learn bass,” former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee said in 2013.

“Roundabout” was by no means Squire’s swan song. Yes continued for more than four decades, playing its first show without Squire as he sought treatment for cancer this past May. There was “Heart of the Sunrise,” another song from “Fragile” that had a bit of a renaissance when it was featured in an arty, not-safe-for-work trailer for Vincent Gallo’s “Buffalo ’66” in 1998. There was “Owner of a Lonely Heart,” an MTV-friendly hit in 1983 that was sort of hard to believe Yes wrote.

Taking stock of this band’s entire career — which lasted longer than four times that of the Beatles — would take awhile.

But as Yes went in and out of style and members came and went, Squire was there for it all.

“For the entirety of Yes’ existence, Chris was the band’s linchpin and, in so many ways, the glue that held it together over all these years,” the band said in a statement, as the Associated Press reported. “Because of his phenomenal bass-playing prowess, Chris influenced countless bassists around the world, including many of today’s well-known artists.”

By the end, Squire wasn’t playing favorites.

“The thing is, every era of Yes has had something to say,” he said earlier this year. “… Things have moved around in the Yes sound picture, but basically, things have stayed the same as well. So I can’t really say which version is the more kickass because every version has come up with something good.”