Regular readers know that I love history and worry we pay far too little attention to it, so here are 11 of my favorite history books of the year. (I say “favorite” and not “best” because I don’t claim to have read everything. And I’m excluding books by people I know well.) There are my three favorites, and eight more that deserve honorable mention as truly excellent. All are in alphabetical order by author.

The favorites:

Keith Houston, “The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time”

“Find the biggest, grandest hardback you can,” advises the author in the introduction. “Hold it in your hands. Open it and hear the rustle of paper and the crackle of glue.” Exactly. Exactly. If you love books you will love this book, and not only because it is beautifully and almost reverentially put together, standing physically for the argument it makes. Books are not like anything else in human history. They have filled houses of worship and toppled empires. But we rarely pause to think about where they came from.

There are other fine volumes in recent years about the history of the book, including outstanding contributions by veteran bibliophiles Robert Darnton and Nicholas Basbanes. But Houston’s wonderful history of the science of the book is irresistible. We all know that Gutenberg and his contemporaries printed with movable type, but how did they make the molds for the letters? Houston investigates. I particularly loved the bit about the debate — yes, the debate — about how papyrus books were made and why they survived the ages. He is also fascinating in tracking the mystery behind the St Cuthbert’s Bible, the oldest surviving bound book.

Thomas C. Leonard, “Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era”

When the Progressives rode to power in the wake of popular fear about corporate power, they brought with them a faith in the expertise of the educated and the ability of the state to order society. “Social selection” should replace laissez-faire. As Leonard reminds us, part of that selection involved eugenics, a belief that we should decide whom to admit as immigrants and whom to encourage to reproduce based on their value to the social order. Needless to say, the cost of these views fell heavily on people of color. The early environmentalists were in on it, too. Eugenics was regarded “as conservation of the race, thus as part of the same project as endangered land and species.” Much of this history, to be sure, has been debated for some time — yes, Woodrow Wilson is still one of the principal villains of the tale — but one hopes that Leonard’s fine volume will put an end to the reflexive habit of many to defend the early liberals, who when it came to people unlike themselves were with rare exception not liberal at all.

Manisha Sinha, “The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition”

The abolition of slavery remains the defining social and political myth of U.S. history. When we tell the history of abolitionism, we tend to choose one of two stories: There’s the history of the white abolitionists and there’s the history of the black rebels. Sinha thinks this is wrong, for three important reasons. First, the black abolitionists, including many who were themselves enslaved, were almost always in advance of the white abolitionists in pressing the great cause, and it is hard to see how abolitionism would have thrived without them. Second, abolitionism itself took place in two waves — a first wave that was deeply bound up with the ideology of the American Revolution, and viewed the problem as one of the battle of ideas and the need for benevolence, and a second wave, spurred by the failure of the first, that involved a good deal less praying and a good deal more demanding. Third, abolitionism cannot be understood without connecting it to other events on the fiercely contested world stage of the day. A long book, but well worth the investment. I read nearly everything published on the subject, but I still learned something new in every chapter.

Honorable mentions, all excellent:

William Domnarski, “Richard Posner”

A fine biography of probably the most influential legal thinker of our day. An intellectual history as well, helping us see how that influence came about.

Robert J. Gordon, “The Rise and Fall of American Growth”

Nothing in the information revolution, Gordon tells us, rivals the five “great inventions” that drove an extraordinary and unduplicable period of growth. Is he right? Judge for yourself.

Nancy Isenberg, “White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America”

The white working class, says Isenberg, is ignored when the story of the U.S. is recounted. As a group, they’re constantly derided. Not all of this is new, but it hasn’t been better told.

Mark Lilla, “The Shipwrecked Mind: On Political Reaction”

A tour de force about what the reactionary really is; not conservative at all, but intellectually radical and socially astute. It’s not about Donald Trump or his movement, but you will have occasion to reflect on (rather than react to) both.

Robert Macfarlane, “Landmarks” (2015, but I didn’t read it until this year)

Part history, part philology, part travelogue, part linguistics, mostly indescribable, except to say that it is one of the most extraordinary books I have read in a long time.

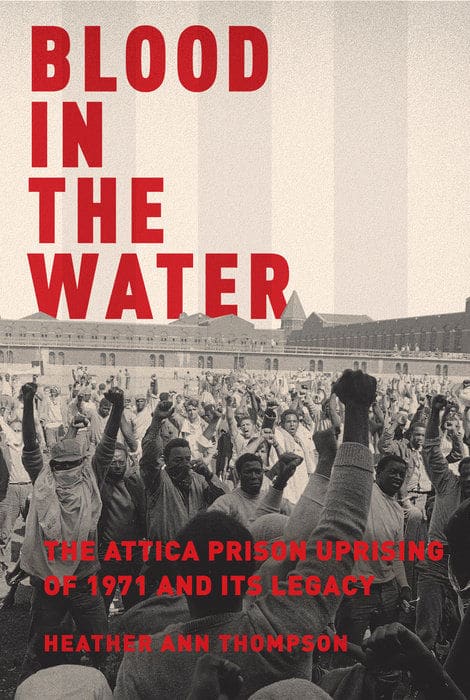

Heather Ann Thompson, “Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy”

A gripping account of what happened at Attica, and chilling from start to finish. Warning: The villain of the piece is Nelson Rockefeller.

Frank Trentmann, “Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, from the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First”

A history not merely of consumption (and attitudes toward consumption) but also of the very idea of goods as a thing to be produced and consumed. Every page fascinates.

Ronald C. White, “American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant”

The 18th president was a far better chief executive than casual history influenced by Southern apologias has led us to believe. I read widely about the 19th century but still learned an enormous amount.

– Carter is a Bloomberg View columnist. He is a professor of law at Yale University and was a clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. His novels include “The Emperor of Ocean Park” and “Back Channel,” and his nonfiction includes “Civility” and “Integrity.”