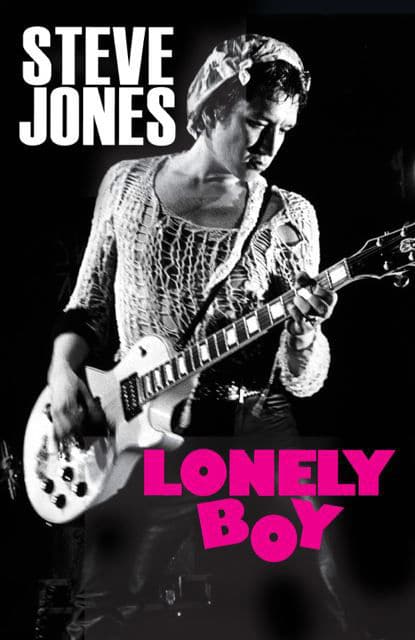

Lonely Boy: Tales from a Sex Pistol

By Steve Jones

Da Capo. 344 pp. $26.99

—

Before the Sex Pistols began the 1978 U.S. tour that would end with their messy split, they had to cancel the first four scheduled shows – including one at the Alexandria, Va., Roller Rink. Two members of the band, it turned out, were too disreputable to get visas automatically. They weren’t the ones who called themselves Sid Vicious and Johnny Rotten, but rather the group’s regular guys, Steve Jones and Paul Cook.

Now Jones has written his memoir, and it fully explains the U.S. visa office’s reluctance. The guitarist had been arrested 13 times, he acknowledges in “Lonely Boy.” Although he doesn’t list each charge, he does recall plenty of infractions. These include drunken driving and drug possession, but Jones’ real passions were shoplifting, burglary and car theft.

The Sex Pistols, who initially existed just from 1975 to 1978, were often portrayed as products of London’s most hopeless precincts. In fact, John “Rotten” Lydon and original bassist Glen Matlock were middle-class, as was Matlock’s self-destructive replacement, John “Sid Vicious” Ritchie. Only Jones and Cook, childhood friends, grew up on the fringe of poverty. And of those two, Jones had by far the lousier time.

Born in 1955 to a single mother, Jones didn’t meet his biological father until he was in his 50s. Eventually, the boy acquired a stepfather, one of several men, Jones alleges, who sexually abused him. After that, the kid found lots of excuses not to be at home. He remembers that he even preferred reform school to his family’s London apartment.

Jones wasn’t good at schoolwork, due to “being dyslexic and/or having ADHD.” He also never wanted to have a regular job (and basically never has). Yet larceny wasn’t simply a way to survive. It was a psychosexual thrill, a feeling he traces to watching his mother loot a lingerie shop when he was a young boy.

There’s another poignant aspect of the author’s early life of crime. Jones loved rock music, and he achieved a sort of intimacy with its stars by swiping their gear: Keith Richards, David Bowie and Mott the Hoople were just a few of his victims. It’s long been part of Pistols lore that Jones outfitted the band with his heists. What wasn’t so clear before this book is that the wannabe musician was, in part, trying to steal his way into his heroes’ lives (if not their hearts).

Most of the revelations in “Lonely Boy” are in its first third. This chronicles the period before “Kutie Jones and His Sex Pistols” – a phrase on a T-shirt for sale at a shop then called Sex – became an actual band whose frontman was Lydon, not Jones. But there are pungent anecdotes throughout the book, even in the parts when Jones becomes, depressingly, a junkie, and then, more depressingly, an L.A. self-help practitioner into transcendental meditation and spinning.

If Jones has now achieved a certain serenity, he makes it sound as if he’s always accepted the universe and his place in it, however crummy. He faults plenty of people but is just as hard on himself, especially for his unfeeling treatment of women. Jones doesn’t indulge much self-justifying in “Lonely Boy,” and when he does, he’s usually quick to admit it. Lydon, though, doesn’t come off well, but the specifics of Jones’ account aren’t that different from those in the singer’s 2014 memoir, “Anger Is an Energy.”

While Jones did eventually become literate, “Lonely Boy” reads as if it was dictated and then sculpted by co-writer Ben Thompson. Still, the conversational prose would have benefited from being pruned of cliches. Clearly intended for a British audience, the book doesn’t translate its more obscure Britishisms, but most of the language can be decoded from context. (What does “he’s brown bread now” mean? Well, “bread” doesn’t rhyme with “alive.”)

“Lonely Boy” is unlikely to charm people without any affection for the strange and sometimes ugly outburst that was British punk rock. Still, it’s distinguished by Jones’ sense of humor, his way with self-deprecating anecdotes and a candor that’s as bracing as the opening riff of the Pistols’ “God Save the Queen.” As he deadpans after one bawdy confession, “This is the good stuff you just don’t get from the guy from Nickelback.”

—

Jenkins is the co-author of “Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation’s Capital.”