The old white sportswriters said the flicking, shying kid with the silly doggerel would get knocked into the ringside seats with one punch. It was 1964, and Cassius Clay hadn’t yet butterflied into the mythic champion Muhammad Ali. He was still incubating in a sweltering Miami Beach gym, where the aging opinion-makers in their narrow neckties watched him work out, disapprovingly, as he rapped out verses on the heavy bag with his light gloves, whap-whap-whap-wump. The rumor was that he was hanging around with Malcolm and the Muslims. But even worse was the way he fought. The kid ran from a punch.

He was still emerging, just a nascent 22-year-old “whose face turned to cameras as flowers answer to the sun,” as his biographer Dave Kindred would write. For just 25 cents, anyone could go watch him work at the 5th Street Gym, an airless, low-ceilinged hotbox up a wood staircase in a slummy part of Miami Beach. Somehow with just 19 pro victories he had quick-lipped his way into a world-title heavyweight bout with Sonny Liston, the gangsters’ pal with the truncheon fists, against whom he was an 8-1 underdog. “He was box-office sacrifice,” remembers Robert Lipsyte, then a 26-year-old sportswriter sent to cover him by the New York Times because the main boxing writer considered him too insignificant to bother with.

Those months of ’64 were maybe the most interesting in his self-made epic of a life. A month before the fight, following a workout, Clay picked up a pen and autographed and dated a pair of his gloves: “From Cassius Clay, Next Heavyweight Champion of the World.” Then he underlined it, heavily. You can see the gloves at the Smithsonian. “He looked at himself as a historical figure, even at that age,” Suzanne Dundee Bonner, the niece of his trainer, Angelo Dundee, told me for Smithsonian Magazine a couple of years ago, when the gloves went to the museum for an exhibit on self-transformation.

Almost nobody believed in the challenger or understood who he was. Nobody. The promoters had such trouble selling tickets to the fight that they cautioned Clay to keep his Muslim conversion quiet. Talk got around anyway that Malcolm X was coming to Miami and there was someone in his camp from the Nation of Islam, which only made the older white sportswriters more suspicious. Red Smith didn’t like those “unwashed punks” of the counterculture. Joe Louis was the right kind of dignified black champion; he kept his mouth shut and called columnist Jimmy Cannon “Mister.”

“Clay didn’t show any respect,” Lipsyte says. “He was very breezy and treated everybody almost casual, off-handed. They kind of lost control of the narrative.”

But strangely, what they distrusted even more than his spiritual defection was his boxing style. As A.J. Liebling put it, he had “a skittering style, like a pebble scaled over water.” His boxing technique seemed to sum up every insurgent, subversive thing about him: Instead of slipping punches, Clay leaned back. He was a runner.

“He was completely unorthodox. Nobody had ever seen a fighter like that,” Kindred says. “If you backed away from somebody, you were seen to be avoiding the fight. No one ever did that. You went forward. They just didn’t like the way he fought.”

Of the 46 sportswriters credentialed to cover the fight, 43 predicted a Liston victory – most of them by knockout, many of them in the first round. After all, Liston had twice decked Floyd Patterson to the floor, so what would he do to this ducking juvenile? Smith called him “the boy braggart.” Cannon called him “all pretense and gas, no honesty.” Arthur Daley of the New York Times predicted, “The loud mouth from Louisville is likely to have a lot of vainglorious boasts jammed down his throat by a ham-like fist.” Liston got in on it, too. Asked what he looked for from Clay in the first round, he said, “I look for him to pull a gun.”

At his final news conference before the fight, Clay told the writers, “It’s your last chance to get on the bandwagon. I’m keeping a list of all you people. After the fight is done, we’re going to have a roll call up there in the ring. . . . I’m going to have a ceremony, and a lot of eating is going on – eating of words.”

But at the weigh-in on the morning of the fight, they said Clay looked scared. He had to be held back by his camp as he yelled at the baleful Liston, “Chump! Chump!” When the fight doctor checked his blood pressure and heart rate and reported it had elevated to 120, the writers took it as evidence that he was terrified. There were rumors that he fled to the airport.

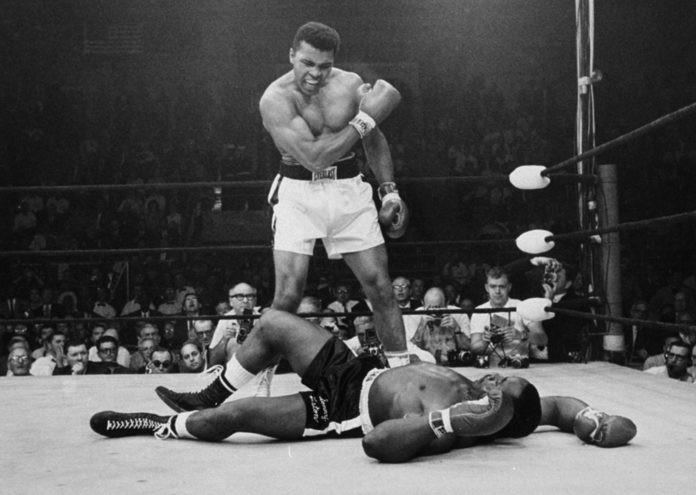

But then they were in the ring, and the bell rang – and the revolution was on, and the militant-spiritualist-rhyming-sage-charismatic was born, with his hands flying and tassled feet dancing. Cannon was converted by the end of the first round after watching Clay reduce Liston to “an aged chophouse waiter with bad feet carrying a heavy tray.” By Round 3, there were cuts on Liston’s face. By Round 7, the former champion sat on his stool refusing to come out with a shoulder injury to try to find the elusive Clay, and the new champion was screaming at the writers, “Eat your words!” Red Smith began to write, with “a mouth still dry from excitement,” admitting in print that “the words don’t taste good.” Lipsyte, too, began typing. Incredibly, he wrote, Clay hadn’t been bragging or huckstering; he had been “telling the truth all along.”

The next morning at his news conference, Clay said, “I’m through talking. All I have to be is a nice, clean gentleman.” And then he publicly acknowledged that he attended Black Muslim meetings.

“I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” he announced. “I’m free to be who I want.”