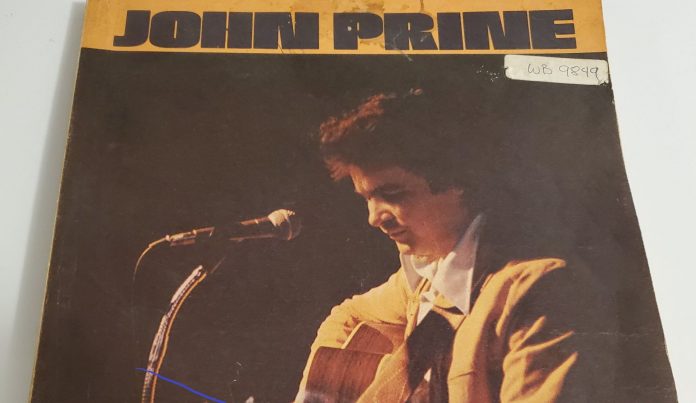

John Prine, the ingenious singer-songwriter who explored the heartbreaks, indignities and absurdities of everyday life in Angel from Montgomery, Sam Stone, Hello in There and scores of other indelible tunes, died April 7 at the age of 73. Prine died of complications from the coronavirus at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

Robert Francis

rfrancis@bizpress-net

I started college after the Vietnam War wound down to a bitter-tasting end, but there were plenty of veterans sharing classrooms with me, particularly when I took some summer classes at Tarrant County Junior College, now TCC.

I was just a fresh-faced punk from the southside of Fort Worth, but I was fascinated by these guys who had returned from service, cashing in on the GI Bill that offered a free education. They deserved something.

While I was interested in earning my way into a degree and doing whatever I was going to be doing with my life, they truly didn’t seem to give a shit about anything. When one was called to the front to talk to the professor about why they hadn’t turned in an assignment, they returned making gestures to the professor hidden to all but his cohorts, who chortled unremittingly at the sophomoric humor.

I don’t even know if they’d been in Vietnam. They didn’t talk about that stuff. They just seemed to be glad to be alive and free from the shackles of their military duty.

Cars, girls, motorcycles? They were happy to wax poetic about all of that. Ask them anything specific about their service and they clammed up like Fort Knox. Anyway, I was an outsider. They let me in a little, but that door could slam shut in seconds, the lock turned until they felt safe again.

I do remember taking a swimming class with one of them and he had a huge red swath of skin on his side. A war injury? I never asked. He could barely stay afloat doing the traditional crawl, but no one could beat him at the backstroke or the butterfly.

While I sweated out doing my homework, they cheered each other on for having the most outlandish excuse for not having their homework.

“My dog ate it,” one would tell the professor, then to the rest of us: “Then he shit it out and I used it to roll a joint.” There was uproarious laughter.

The girls in the class – some of whom had graduated with me – were scared of them. All one of the guys had to do was stare at the girls and the girls would quickly move along. The more nervous the guys made the girls, the more they would laugh about it. There was something dangerous about them. That, too, was a bit alluring.

One of the guys (I’ll call him Harry, because his hair was out of control) played the harmonica – anytime, anyplace, even the library – and he kept asking for someone who could play the guitar, so he could have a Brownie McGhee to his Sonny Terry, names I didn’t know then. I went home and got out my Mel Bay Book I and went through my folkie chords just in case it might happen.

I sat with them during lunch – the odd man out with relatively short hair, a civil tongue and squared-away demeanor. They would discuss things way out of my league – where to get the best deals on booze, deals on food, bars with cheap drinks and beautiful women – or do I have those last two adjectives mixed up? Important things like that.

Meanwhile, I would look over their papers for class and try to get their attention so they could learn something, but they didn’t really seem to care. “Sure, go ahead, change it,” they’d say, then go back to telling a story about some guy they knew who had persistent bad luck.

They tolerated my presence. I laughed at jokes they’d told each other 100 times. They were new to me.

At one point, Harry, the nominal leader of the guys, needed some welding done on his car, so I suggested he head down to my grandfather’s place to get it done. He did and it was weird seeing this longhaired, funky, slightly buzzed hippie interact with my granddad. My grandfather was into health foods at the time, a hippie staple at the time, and so they had something to bond over besides arc welding.

That won me some points with Harry and the guys. Granddad was cool.

Getting the high sign from Harry that I was cool sealed the deal with the rest of the guys. I helped some of the other guys try to get some of their schoolwork done. They were excited to get a C, while I was mortified by a B.

They invited me to some parties where I was even more the odd man out, but I did get the nerve to play some rudimentary guitar behind Harry as he wailed on harmonica. They took it all in stride, while I felt like I was on top of the world. Or maybe I should say I was on a natural high and they were just, well, high.

One of the records in Harry’s collection was John Prine’s self-titled first album. At some point in the night after the beers had flowed and the cigarettes or whatever they were smoking were getting low, they would put on the album and they would belt out Sam Stone along with Prine:

There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where the money goes,

Jesus Christ died for nothin’ I suppose …

They screamed it like some sort of survivor’s anthem. And to them it was. Prine’s tale of a soldier’s troubled return home were the real thing for these guys.

I have no idea if they did any harder drugs. Even though I had seen plenty of drugs on Hemphill Street, where my grandparents’ business was, I certainly wasn’t knowledgeable. They probably did, but I didn’t notice or didn’t want to notice. I was more interested in their attitude toward life. They had an exuberance that I found intriguing.

And that danger thing. This was no longer high school.

Also, unlike high school where you see the same faces year after year, when I returned for the fall semester, most of them were gone. Harry had gone to California. Somebody got married. Somebody got a job. Life happened.

Whatever mojo they had for that brief summer evaporated with them, though they left a little of it with me.

A few years later I was at the University of Maryland, once again a fish out of water, trying to make friends. A guy named Charlie pulled out a guitar at a party and started playing Sam Stone. I joined in, remembering those days with Harry and the guys. To me, Sam Stone was a real person, one of the damaged, dangerous guys I met so long ago. Unlike Sam, at the time they were full of exuberance, pedal to the metal and beyond, ready to take life at full, heedless speed. I wonder how long that reckless ride lasted? Or if, like Sam Stone, they “popped their last balloon” traded life “for a flag-draped casket on a local hero’s hill.”

Robert Francis is editor of the Fort Worth Business Press.