Milt Okun, a classically trained pianist and music impresario who shepherded acts such as Peter, Paul and Mary and John Denver to national renown in the 1960s, and who transformed opera star Plácido Domingo into an unlikely pop sensation in the 1980s, died Nov. 15 at his home in Beverly Hills, California. He was 92.

The cause was kidney failure, said his daughter, Jenny Okun Sparks.

Okun’s producing credits spanned seven decades and many genres and artists, from the folk group the Chad Mitchell Trio to the Starland Vocal Band (“Afternoon Delight,” 1976). He saw the potential of the dubious pairing of the Spanish operatic tenor Domingo and the shaggy-haired Denver, pursuing Domingo for years before he agreed to join the project. “He kept putting me off,” Okun once said. “I think he thought I was some kind of overage groupie.”

Their crossover smash “Perhaps Love” (1981) helped launch a micro-craze of male duets, including Willie Nelson and Julio Iglesias crooning “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before,” and paved the way for Domingo’s later pop-operatic work as one of the Three Tenors.

On Facebook, Domingo, the Spanish operatic tenor, paid tribute to Okun as “the man with great vision that firmly believed in me and gave me my breakthrough role in the world of pop music.”

Okun’s independent music publishing company, Cherry Lane Music, groomed a stable of songwriters such as will.i.am and other members of the Black Eyed Peas, John Legend, Ashford & Simpson, Tom Paxton and Irving Burgie (who wrote many of Harry Belafonte’s hits). The business, which was sold to BMG in 2010, also acquired the rights to Denver’s song catalogues and entered partnerships involving music rights with NFL Films, DreamWorks, WWF and other businesses.

At Cherry Lane, Okun was the creative force behind Music Alive!, a publication that teaches music appreciation to schoolchildren. It stemmed from his early years as a junior high school music teacher in New York before immersing himself in the folk-music revival of the 1950s and 1960s.

During those years, Okun was a central figure in its epicenter: Greenwich Village. He made recordings as a singer for small folk labels, arranged several albums for Shlomo Carlebach – known as “The Singing Rabbi” – and became an arranger and conductor for Belafonte.

Belafonte ended the relationship, Okun later recalled, after Okun dared to disagree on the tempo for “Hava Nagila.” He said it was “humiliated” but later called their separation a blessing that freed him to form Cherry Lane (named after the Greenwich Village theater he lived over) in 1960.

In that role, Okun shaped innumerable acts, most notably Peter, Paul and Mary. He also produced, promoted and published the work of singer-songwriters such as Paxton, Laura Nyro and other performers who helped bring folk music to mass audiences by bridging traditional and contemporary sounds.

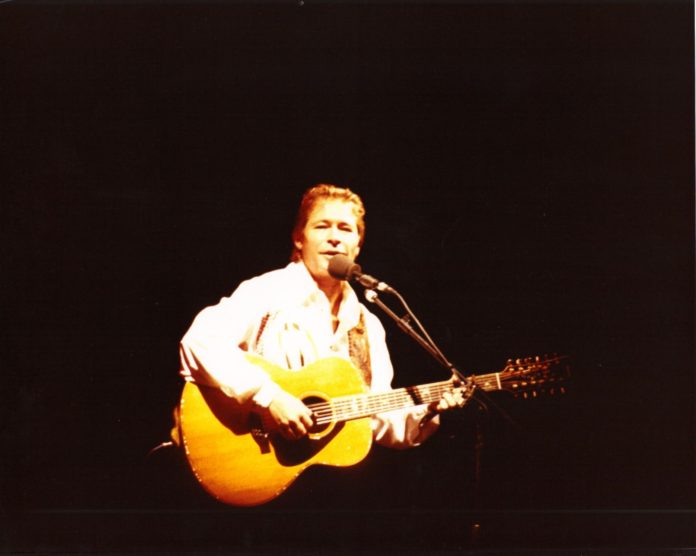

After Chad Mitchell left his namesake trio in 1965, Okun saw spectacular promise in Denver, the young singer-songwriter who took his position in the group. Okun later produced many of Denver’s solo albums – containing songs such as “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” “Rocky Mountain High” – that would propel his career until his death in an airplane crash in 1997.

The various titles Okun held at any one time – music director, publisher, producer – did not fully reflect his range of responsibilities. He matched artists with songs to showcase their strengths, persuading disc jockeys to play the music, obtained important bookings on stage and TV, and enforced royalty collection, among other duties.

Mark Moss, editor of the folk music magazine Sing Out!, said the folk boom “was led to a great extent by impresarios, people who were organizers of stuff, even more so than the artists themselves.” Okun, he continued, “was one of a handful of incredibly influential publishers, organizers, managers, directors, presenters who sprang up during that era.”

Okun lumped producers into two categories: those with technical wizardry in the studio and those who are immersed in the music itself. He placed himself squarely in the latter, and he said his strengths proved fortuitous on at least one occasion.

“One day, Denver came in with this beautiful melody on a new song,” he once told an interviewer. “I said, ‘John, the only problem is that it’s the exact melody of Tchaikovsky’s 5th symphony, the second movement.’ ” Okun played the melody on the piano, and Denver rewrote all but the first phrase. The resulting piece became one of the entertainer’s biggest hits, “Annie’s Song.”

“A technology-oriented producer would have let his original song go through, and he would have been sort of ridiculed,” Okun said.

Denver once observed that Okun’s appearance – the dark-rimmed glasses, the sedate business suits – often masked his keen artistic sensibilities; he also apparently had a financial manager given to flashy clothes. “I have a producer who looks like an accountant,” he quipped, “and an accountant who looks like a producer.”

Milton Theodore Okun was born in Brooklyn, New York, on Dec. 23, 1923, to Jewish immigrants from Russia. His father made a living as an engineer and insurance salesman. Both parents embraced left-wing politics and raised their children in a secular home emphasizing music and civil rights. They ran a small resort in the Adirondacks where Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie were among the performers.

From an early age, Okun aspired to a career as a classical pianist. But at age 14, he contracted a kidney inflammation for which there were no effective antibiotics. During a years-long convalescence, he lost so much strength in his hands that a concert career was no longer possible.

Instead he became a New York public schools teacher after obtaining degrees in music education from New York University in 1949 and Ohio’s Oberlin Conservatory of Music in 1951, the second a master’s.

A respected musicologist, he edited volumes including “The New York Times Great Songs of the Sixties” (1970) and “The New York Times Great Songs of Lennon & McCartney” (1973). He also wrote a memoir, “Along the Cherry Lane” (2011), with his son-in-law, Richard Sparks.

Besides his daughter, of Beverly Hills and London, survivors include his wife of 58 years, Rosemary Primont Okun of Beverly Hills; a son, Andrew Okun of Los Angeles; and three grandchildren.

For all the hits and stars that Okun introduced to the musical world, he often demurred on his role as a cultural tastemaker. “I never knew what was going to happen in pop music, even when it was happening,” he told The Washington Post in 1970. “The first time I saw Peter, Paul and Mary, I said to my wife, ‘That group is never going to make it.’ I wanted the men to shave off their beards.”