TECUMSEH, Okla. — They had been expecting a full processional with a limousine and a police escort, but the limousine never came and the police officer was called away to a suspected drug overdose at the last minute. That left 40 friends and relatives of Anna Marrie Jones stranded outside the funeral home, waiting for instruction from the mortician about what to do next. An uncle of Anna’s went to his truck and changed from khakis into overalls. A niece ducked behind the hearse to light her cigarette in the stiff Oklahoma wind.

“Just one more thing for Mom that didn’t go as planned,” said Tiffany Edwards, the youngest surviving daughter. She climbed into her truck, put on the emergency flashers and motioned for everyone else to follow behind in their own cars. They formed a makeshift processional of dented pickups and diesel exhaust, driving out of town, onto dirt roads and up to a tiny cemetery bordered by cattle grazing fields. In the back there was a fresh plot marked by a plastic sign.

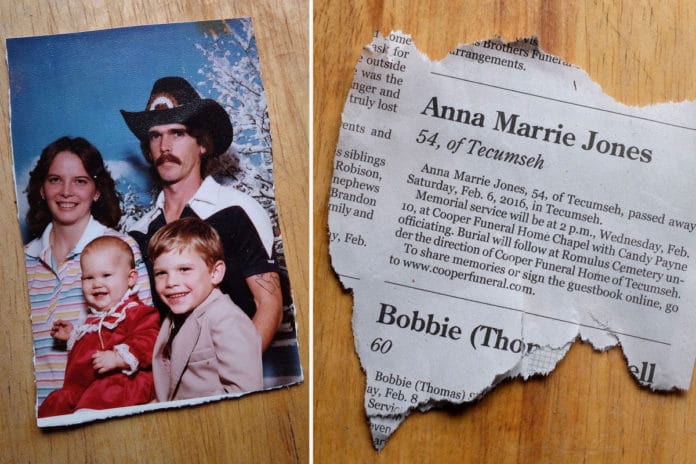

“Anna Marrie Jones: Born 1961 – Died 2016.”

Fifty-four years old. Raised on three rural acres. High school-educated. A mother of three. Loyal employee of Kmart, Walls Bargain Center and Dollar Store. These were the facts of her life as printed in the funeral program, and now they had also become clues in an American crisis with implications far beyond the burnt grass and red dirt of central Oklahoma.

White women between 25 and 55 have been dying at accelerating rates over the past decade, a spike in mortality not seen since the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s. According to recent studies of death certificates, the trend is worse for women in the center of the United States, worse still in rural areas, and worst of all for those in the lower middle class. Drug and alcohol overdose rates for working-age white women have quadrupled. Suicides are up by as much as 50 percent.

What killed Jones was cirrhosis of the liver brought on by heavy drinking. The exact culprit was vodka, whatever brand was on sale, poured into a pint glass eight ounces at a time. But, as Anna’s family gathered at the gravesite for a final memorial, they wondered instead about the root causes, which were harder to diagnose and more difficult to solve.

“Life didn’t always break her way. She dealt with that sadness,” said Candy Payne, the funeral officiant. “She tried her best. She loved her family. But she dabbled in the drinking, and when things got tough the drinking made it harder.”

There were plots nearby marked for Jones’s friends and relatives who had died in the past decade at ages 46, 52 and 37. Jones had buried her fiance at 55. She had eulogized her best friend, dead at 50 from alcohol-induced cirrhosis.

Other parts of the adjacent land were intended for her children: Davey, 38, her oldest son and most loyal caretaker, who was making it through the day with some of his mother’s vodka; Maryann, 33, the middle daughter, who had hitched a ride to the service because she couldn’t afford a working car; and Tiffany, 31, who had two daughters of her own, a job at the discount grocery and enough accumulated stress to make her feel, “at least a decade or two older,” she said.

Candy, who in addition to being the officiant was also a close family friend, motioned for Tiffany and Maryann to bring over the container holding their mother’s cremated remains. They opened the lid and the ashes blew back into their dresses and out into the pasture.

“No more hurt. No more loneliness,” Candy said.

“No more suffering,” Tiffany said.

They shook out the last ashes and circled the grave as Candy bowed her head to pray.

“We don’t know why it came to this,” she said. “We trust You know the reasons. We trust You have the answers.”

—

All anyone else had so far was a question, one that had become the focal point of congressional hearings, health summits and presidential debates: Why?

Why, after 50 years of unabated progress in life expectancy for every conceivable group of Americans – men, women, young, old, rich, poor, high-school dropouts, college graduates, rural, urban, white, black, Hispanic or Asian – had one demographic group in the last decade experienced a significant percent increase in premature deaths? Why were so many white women reporting precipitous drops in health, mental health, comfort and mobility during their working-age prime? Why, over the last eight years alone, had more than 300,000 of those women essentially chosen to poison themselves?

“It’s a loss of hope, a loss of expectations of progress from one generation to the next,” said Angus Deaton, a Nobel Prize-winning economist who had studied the data.

“What we’re seeing is the strain of inequality on the middle class,” President Obama said.

“Erosion of the safety net,” Hillary Clinton said. “Depression caused by the state of our country,” Donald Trump said. “Isolated rural communities,” Bernie Sanders said. “Addictive pain pills and narcotics,” Marco Rubio said.

There were so many paths in the America of 2016 to what coroners termed “a premature and unnatural death,” and one version was what had happened to Jones: Another night of drinking that ended in the emergency room, her seventh trip in the last four years. A diagnosis of end-stage liver failure. A week in a nursing home. A quiet death followed by burial four days later.

And now her family had caravanned from the graveyard to a memorial potluck, hosted at a senior center in a part of the country where fewer people were becoming seniors. The early death rate had risen twice as fast in rural Oklahoma as in the rest of the United States, and the walls of the center were adorned with posters about prescription overdose and the phone number for a suicide hotline. Candy set up a buffet table and brought in her homemade biscuits. Other relatives came with macaroni salad, coleslaw and baked chicken. They lined the food on a foldout table near a collection of photos from Anna’s life. Here she was riding a horse on her 10th birthday. Here she was behind the register at the hamburger counter, 13 years old and straight-shouldered in her uniform.

“So proud. So confident,” said Kaitlyn Strayhorn, a friend, looking at the photo.

“She had to lie and say she was 16 to get that hamburger job,” said Junior Sides, her brother. “She was a hard worker. Had it going good there for a while.”

She had been born on the way to the hospital in the back seat of her father’s car, the ninth of 10 children, and the family joke was that Anna had never stopped hurtling her way into the world. At a time when life on the far edges of the middle class came with dependable opportunities, her older siblings left home for the quarry, the machine shop and the military, and Jones moved out along with them even though she was only 17. She rushed off to get married in Reno, Nev. She got a job at a Kmart snack bar in California and worked her way up to manager. She was good at making people feel comfortable, at listening without judgment and aligning herself with the customer. She clipped coupons for regulars and gave free drinks to people who couldn’t afford them. By the time she reached her mid-20s, Kmart was training her to become a regional manager. She had her own trailer in Ferndale, Calif., two children, two cars and a retirement savings account.

But the promotion never materialized and the marriage took work, and after a while her eagerness turned to restlessness. She drank more. She tried drugs. She left Kmart. She was arrested for drinking and for failing to pay her taxes. Her marriage unraveled and she moved home to Oklahoma with the kids. She helped push Maryann and Tiffany to finish high school, and then once all of her children left home she lived for a while with her mother, then her daughter, then her fiance and finally her son for the last years of her life.

Her brother Junior hadn’t seen her for the last several months, and in the most recent photos her skin had turned pale and the fatigue lines beneath her eyes had hardened into deep red marks. “Sick and tired of being sick and tired,” Junior said, and then he filled his plate and sat down at a table with her children and her friends.

“I think in some ways she was ready,” he said. “You can see how much it took out of her.”

“Sometimes the hard things in life eventually break you,” said Kaitlyn, Anna’s friend. Kaitlyn had lost one infant child to SIDS. She had lost another to miscarriage in the third trimester.

“It’s a test of how much you can take,” Junior said. He had been addicted to prescription pills and then recovered. He had been shot five times by his son and chosen to forgive him.

“But there’s a choice in how you handle it,” Candy said. “That’s what I always told her: You’re choosing this. I’m sorry, but you are.”

“Alcohol is a powerful drug,” Davey said.

“Everybody needs a little something,” Maryann said.

They finished eating and cleared their plates. Davey went outside to smoke a cigarette. Maryann found her way to an empty car and took a nap. After a while it was just Tiffany and a few others left in the senior center to clean up the dishes. “You have all this under control?” the last remaining relative asked Tiffany, already heading out the door, because with Tiffany it never seemed like a question. She always had it under control. She was the strongest sibling, the most responsible, the one who had gone to a year of college, the head of pricing at a grocery store, the dieter, the rare woman in rural Oklahoma whose well-being nobody seemed to worry about. And now she was alone at the sink, gripping hard onto the handle, closing her eyes.

“When does it get easier?” she said.

—

She finished the dishes and drove home to a trailer where everyone was waiting for her, and where all of them needed something. Her 4-year-old daughter wanted dinner. Her disabled 1-year-old daughter had another doctor’s appointment in Oklahoma City. Her husband, Chad, needed their car to run errands. Her boss missed her at work. Her brother needed money for rent or a place to live. And then there was their trailer itself, which they had purchased for $2,000 from a cousin because they wanted to tear it down and put a new trailer on their beautiful country lot. But now it was two years later and they were still in the old trailer, with faulty electricity, a broken shower and no door for the bathroom.

“A work in progress,” Tiffany called it, and sometimes she thought that was true of so many lives in this in this part of Oklahoma. Goals receded into the distance while reality stretched on for day after day after exhausting day, until it was only natural to desire a little something beyond yourself. Maybe it was just some mindless TV or time on Facebook. Maybe a sleeping pill to ease you through the night. Maybe a prescription narcotic to numb the physical and psychological pain, or a trip to the Indian casino that you couldn’t really afford, or some marijuana, or meth, or the drug that had run strongest on both sides of her family for three generations and counting.

“Shot and a beer for Mom?” she said now, raising a shot glass to her husband. He shook his head. She drank the shot and sat down next to him in the living room.

They had gotten drunk with her mother dozens of times, and it was almost always fun. She was a happy drinker who made for good company around a fire, with fun stories and a throaty laugh. After she was diagnosed with cirrhosis in 2009, doctors had said her prognosis was good if she stopped drinking. Her liver had a few years left. She would be eligible for a transplant. And for a few months at a time she had managed to quit, but reality often left her depressed. Her fiance died. A few nephews were arrested for using drugs. She filed for bankruptcy. Her mother died. She drank until she was too sick to work.

“I could be mean to her sometimes,” Tiffany said now, in the living room. “I kept saying to her, ‘You’re killing yourself.’ “

“You were watching her die,” Chad said. “You were the one taking her to all those doctor appointments.”

“It made me so angry,” Tiffany said.

“You were just trying to pull her out of the spiral,” Chad said.

They each had gone through spirals of their own. Chad had been arrested for driving under the influence three times in the years after his mother’s death before straightening himself out to take care of the children. Tiffany had sometimes been going to work hung over until she became pregnant, and then she went nine months without a beer or cigarette. “I’m not going to make my problems my kid’s problem,” she had told her mother then, because there was still hope that her children would have it easier. Maybe the world would open up to them.

“Don’t you want to see what your grandchildren become?” Tiffany would ask her mother. “Don’t you want to be there for them?”

But even though Anna loved her granddaughters – babysat them, admired the way Tiffany and Chad cared for them, bought them whatever she could – she could never give them that. She quit drinking and then started again, quit and then started. She fell down at her house and broke a leg. She had to use a wheelchair. She lost her car and then her driver’s license. She stayed in her living room and watched TV for hours at a time unless Tiffany came to pick her up.

Tiffany stood up from the couch. She walked to the kitchen and reached into the cooler.

“Babe,” Chad said, looking at her.

“What?” she said, but she closed the cooler and came back to him empty-handed. She wrapped her hand around his and leaned against his shoulder.

“She had family. She had friends,” she said. “I don’t understand why it wasn’t enough.”

—

There were days when the vast emptiness of rural Oklahoma could make someone feel alone – when the only sound was wind, and the prairie looked small beneath the sky, and the one car bouncing along the rutted gravel roads was Candy Payne’s mail truck, circling its way from one house to the next.

It had been four days since she presided over her friend’s funeral, and now she was back on her usual U.S. Postal route: 404 mailboxes in 126 square miles of Pottawatomie County. The roads were in fact dirt trails, the houses were mostly farmsteads equipped with well water, and what she called the “traffic considerations” were turkey, deer and coyotes that darted across her route. In one of the most isolated parts of the United States, she was the only thread that connected one house to the next, and her customers were often standing at their mailboxes and watching for her. There were pill poppers waiting for packages of medication and people on disability waiting for their government check. There were lonely retirees who waited only for a wave, a smile or a few minutes of conversation with their only visitor of the day.

“Anything for me today?” said one woman, as she watched Candy drive by the long dirt driveway to her house.

“Not today,” she said. “Better luck tomorrow.”

The route took six hours, and she drove with a cigarette in one hand and an inhaler on the dashboard. She followed unsigned roads to addresses she knew by heart, stopping at houses in disrepair with cars rusting away in the weeds. Most of her route had been settled by land run in the late 1800s, all property free to whomever came first, and for generations it had been populated by farmers, dreamers and opportunists. But now the farming had gone away to big companies and the poverty rate had climbed above 20 percent. “A whole lot of places just going to pot,” she said, grabbing another phone book out of the mail sack in her passenger seat, stuffing it into a box.

She was 62 with bad knees and a nagging cough, but she had no intent on retiring. Many of her friends had died in their 40s and 50s. Her husband was dead of cirrhosis and the Vietnam War veteran she lived with now was managing his way through liver disease with narcotic pain patches. She believed she had made it into her 60s as a woman in rural Oklahoma not just by avoiding alcohol and pills but also by forcing herself out into the world. “You see people. You talk a little bit,” she said. “Otherwise you just sit at home and the end closes in. “

A pickup came moving toward her from the opposite direction, and she pulled over to let it pass.

“Howdy, Candy,” the driver said, slowing down to wave. “Sure is a windy one.”

“I’m eating dust,” she said, smiling back, continuing down the road.

She had watched the end close in on Anna, even as she tried to draw Anna out. They had talked over the phone every few days, and then a week before Anna’s death Candy had gone over to visit her house, a two-bedroom rental near the funeral home in Tecumseh. Anna’s clothes were piled up in a corner and there were no sheets on her bed. There was a hole in the living room wall, and the air smelled of sweat and smoke. Candy went into the kitchen to try to clean up a week’s worth of unwashed dishes – “Relax. Breathe through your mouth. You can do this,” she had told herself – but the plastic plates were covered in mold and eventually she had decided to throw them out.

When Anna lost consciousness for the final time in the nursing home, Candy had gone to sit with her and hold her hand. All of Anna’s children were also there – Davey, Maryann and Tiffany – and they looked exhausted from sitting by her bed through the night. Candy sent them home to rest, and after a while she went home, too. She had seen so many people die of cirrhosis, and the disease usually took its time in the final stages. Sometimes weeks. Sometimes months. But then the next morning she got a call telling her Anna had died in the night.

“That’s one thing I keep thinking about,” Candy said now, stuffing a phone book into another mailbox, nearing the end of her route. “I wish she wasn’t alone at the end.”

She drove up to the last address, hers, and turned off the engine. “The route’s complete,” she said, notifying a supervisor. The road behind her was quiet. There was only wind and a few hundred homes scattered across the plains.

—

One of those homes had been Anna and Davey’s, and now it was just Davey inside with the doors locked and bed sheets blocking the windows. His mother’s medications were still stacked on the counter. Those were her clothes strewn across the living room, her microwaved jambalaya leftovers in the sink and her $8.75 liter of Heaven Hill Vodka pushed against the couch. Davey reached for the bottle and took a gulp. He chased it with water and then drank again.

“Last day,” he said. “Tomorrow it’s detox, getting a job, all that.”

The day before had also been the last day, and so had the weekend before that, and now it was two weeks until $350 in rent came due on the house. He had no money of his own and nowhere else to go. For the last five years he had been living with his mother and surviving on her disability payments and $197 in food stamps. She had supported him and he had been her caretaker, lifting her out of bed in the mornings and pushing her wheelchair up the hill to a tornado shelter whenever a storm hit. He had monitored her medications, washed her jaundiced skin and dealt with the diapers.

He had even tried to keep her from drinking, just as the doctors insisted. But he was buying vodka with her money and drinking it in front of her, and she would yell and beg and then threaten to withhold Davey’s cash so he couldn’t drink either. Eventually he had decided to compromise by rationing out her liquor, filling half of a pint glass with vodka that she could nurse through the night. But sometimes he would pass out on the couch or go to the bathroom, and whenever he came back the bottle looked emptier than before.

“Do you blame me?” he had asked Tiffany once, a day after the funeral.

“You did the best you could,” Tiffany had told him. “There’s no sense obsessing over it.”

Now the house was empty and there was nothing to do except reach back for the vodka and watch the same shows they’d always watched together: “Family Feud,” “Sleepy Hollow,” “Modern Family” and whatever else came through on the rabbit ear antenna. Day turned into night. Night turned back into day. He needed to shave, cut his hair and start putting in applications. “Last day,” he said again, rolling his own cigarette, reaching down for the bottle.

They had lived together for five years, and yet there were so many questions he had never asked her. Did she know she was dying? Was she scared? Was she ready? “I keep having these conversations in my head,” he said, and sometimes, as the days stretched on with no visitors, he would pick up his phone and call another relative to talk. “What happened? Was it my fault?” he would ask each time.

It was a choice, Tiffany said.

It was stress, Maryann said.

It was everything wearing her down, Junior said.

It was just the way it went, Candy said.

Davey sipped from the bottle. He gulped from the water. He lay back on the couch, where lately he had been having a recurring dream. He was sitting in the living room with his mother, a woman not yet 55 who had some color back in her cheeks and her hair pulled into a braid. He wanted to be honest with her, to tell her she was dying, and finally he blurted it out: You’re dying, he said, but she didn’t look back at him. You’re dying, he said again. You’re dying! But the TV was blaring, the bottle was in her hands, her eyes were glazed over, and she was too far gone to hear him.

—

ABOUT THIS SERIES

Since the turn of this century, death rates have risen for whites in midlife, particularly women. The Washington Post is exploring this trend and the forces driving it.