BOSTON — Lloyd Matsumoto awoke from his liver transplant last month to find his surgeon more than pleased with the results. The new organ had begun producing bile almost immediately, a welcome signal that it had quickly started to function well.

That may be partly because of the way Matsumoto’s liver traveled from Tufts Medical Center across Boston to Massachusetts General Hospital. Instead of being packed in ice for the 4 1/2 hours it was outside the abdomens of donor and recipient, the liver was essentially kept alive in a device that maintains its temperature, perfuses it with oxygenated blood and monitors its critical activity.

“They say I’m going to live a normal life span,” said Matsumoto, a 71-year-old biology professor who is now back home in Darrington, Rhode Island. “I’m living proof that it works.”

For all the advances in transplant surgery in the 62 years since doctors first moved a kidney from Ronald Herrick to his identical twin, Richard, the method of transporting organs remains remarkably primitive. A harvested heart, lung, liver or kidney is iced in a plastic cooler, the kind you might take to the beach, then raced to an operating room where a critically ill patient and his surgical team are waiting.

The new approach flips that idea — emphasizing warmth instead of cold and maintaining an organ’s natural processes rather than slowing them down. That may speed an individual heart or liver’s return to service, and it offers the eventual possibility of more: the potential to reduce the chronic shortage of organs for transplant by expanding the pool of usable ones.

Earlier clinical trials established that this technique is safe for transporting donated hearts and lungs. But Matsumoto’s surgeon, James F. Markmann, chief of the division of transplantation at Massachusetts General and head of the liver trial, cautioned that neither idea has been proven for that organ. That’s one of the reasons a study is underway. But Markmann said doctors and patients may be on the cusp of a “new start to this area.”

Many donor hearts are unavailable today because too much damage would occur when the blood supply is cut off and the organ is put on ice for hours. The big question is whether keeping them warm will increase the supply, said Michael G. Dickinson, a heart-failure cardiologist at Spectrum Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Dickinson is part of a separate heart-transport study designed to address that issue.

“Is this better overall than the standard method?” he asked. “We would hope so. But we don’t know.”

A Massachusetts company, TransMedics, founded in 1998 by a heart surgeon, developed the Portable Organ Care System being used in the U.S. trials. Competitors here and abroad also are testing alternative technology.

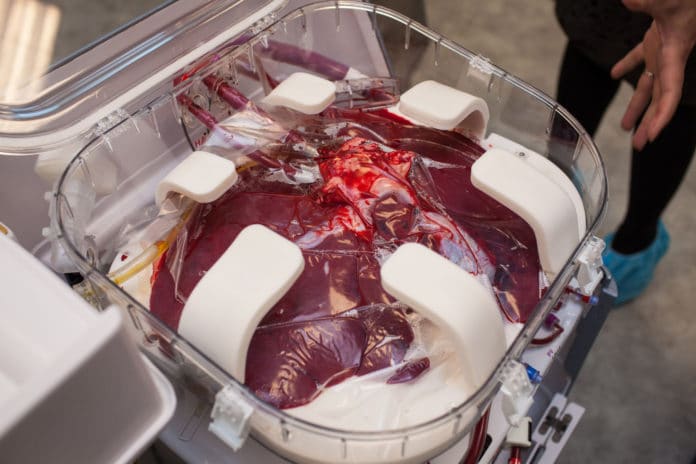

The TransMedics device encloses the organ in a plastic box that attaches to a wheeled cart and can be removed to fit in a vehicle or aircraft. Blood, nutrients and fluids are pumped through tubes into the liver. Heaters warm the blood. Sensors monitor critical functions during the trip, relaying them to doctors wirelessly on a control screen. Specialists can alter a number of conditions — including oxygen levels and pressure in veins — with a touch of the panel.

The TransMedics system, first tested in Europe in 2006, is awaiting approval by the Food and Drug Administration for commercial use with hearts and lungs in the United States. The liver trial is a first-level safety study.

In Australia and parts of Europe, the device has been approved and used about 200 times commercially, according to a company spokeswoman.

A substantial remaining obstacle is cost, including whether insurance, Medicare and Medicaid will cover the $250,000initial purchase, the $45,000 price of each organ container — which are used only once — and the staff time needed to transport an organ this way.

Nearly 31,000 organs were transplanted in the United States last year, including 2,804 hearts and 7,127 livers. But the sizable gap between demand and supply generally widens every year, leaving tens of thousands of people on waiting lists. An average of 22 people die each day waiting for transplants.

David Klassen, medical director for the United Network for Organ Sharing, the nonprofit organization that runs the U.S. organ procurement and transplantation network, agreed that devices such as the organ-care system could help ease the shortage if they make currently unusable organs available for transplant. Cost, he said, is still a barrier to widespread adoption of the devices, but with trials underway it is early for decisions on coverage.

There are two types of death in the transplant field — brain death and cardiac death. Donor hearts are useful only after brain death, because the heart continues to pump and oxygen-rich blood continues to circulate. In cardiac death, reduced circulation — known as ischemia — causes too much damage to the heart muscle to allow transplantation.

Australian doctors last year transplanted three hearts after cardiac death, waiting as little as two minutes to harvest the organs. That effort and another like it have raised ethical questions about how soon surgeons should remove any organ after the heart stops beating. In the United States, the standard is five minutes.

“We can’t have a Wild West situation where surgeons just essentially come up with their own criteria,” said Robert Veatch, a professor emeritus of medical ethics at Georgetown University’s Kennedy Institute of Ethics.

Restarting livers, lungs and other organs harvested after circulatory death raises another issue, Veatch said. “If you’re restarting a heart, can you also say the circulatory system has been irreversibly stopped?” he asked.

In a brain-dead donor, transport and harvesting time are the enemy. When Marvin Vandermolen received his new heart April 16 at Spectrum’s Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center, the donor was 2 1/2 hours away and 7 1/2 hours passed from the time the organ was taken until it was placed in Vandermolen’s chest. That is nearly double the allowable four hours under the protocol for hearts transported on ice.

But because Vandermolen’s heart was kept beating on the TransMedics device, it was in fine shape when it arrived for transplant and functioned well, according to his surgeon, Martin Strueber.

“We can keep a donor heart out of the body longer than we would do with any cold storage method,” Strueber said. “The heart is not sitting in a box. It is sitting in a system and is perfused with warm blood.”

After a month in the hospital, Vandermolen, 63, was headed home, focused “on eating something that really sounds good to me, and that sounds like meatloaf,” he said.

Donations after cardiac death also are problematic for livers, Markmann said. Thirty minutes without circulation is the current standard. Even within that time, about 30 percent of livers suffer some scarring in bile ducts. If the study shows promise in reducing injuries, future research will probably examine how much longer livers can endure ischemia.

Markmann said he was gratified to see how quickly Matsumoto’s donated liver responded. Until the study at six U.S. sites is completed later this year, it’s impossible to know the impact of the TransMedics device. But Markmann said in an email that “it was my impression” that the new transport method “contributed to [the liver’s] excellent early function.”

Early signs of Matsumoto’s liver problems began 25 years ago. Doctors eventually discovered that he had a form of cirrhosis — permanent scarring and damage to liver function — that is not related to alcohol, Matsumoto said. There is no cure, and when his symptoms became severe, one primary-care doctor told him that “no one is going to give a man your age a new liver,” he said.

But that wasn’t true. He qualified as a recipient and signed up for Markmann’s study. As a test subject, he could have been randomly chosen for the current standard of care — a liver transported on ice – or the experimental procedure that uses the TransMedics apparatus. A computer chose him for the latter and he became just the third person at Massachusetts General to receive his liver that way.

The 11-hour transplant surgery began on April 27 and was completed the next day. When Matsumoto awoke, “I was told I have a new birthday,” he said, “which was the 28th of April.”