Google and Alcon

Google Inc. is teaming up with Swiss drugmaker Novartis AG’s Alcon unit to develop smart contact lenses with embedded electronics to improve vision and monitor health.

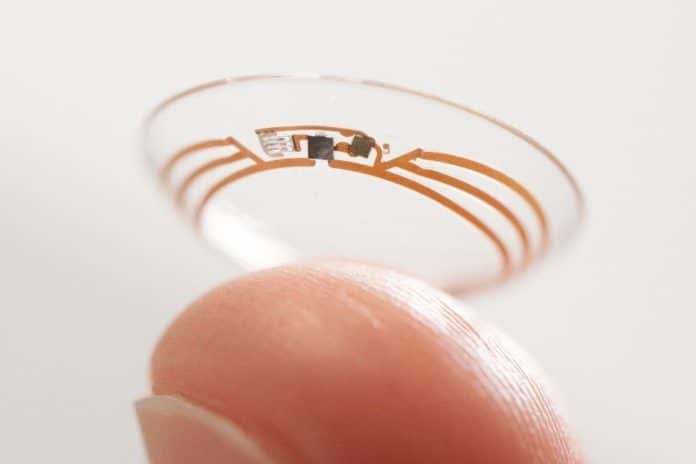

Fort Worth-based Alcon will work with Google’s secretive Google X division on lenses with non-invasive sensors, microchips and embedded miniaturized electronics to monitor insulin levels for people with diabetes, or to restore the eye’s natural focus in people who can no longer read without glasses, Basel-based Novartis said in a statement. No terms of the deal were disclosed.

Novartis expects to get the first prototypes sometime in 2015 and may start marketing the products in about five years, Novartis Chief Executive Officer Joe Jimenez said in 2014. Jimenez identified eye care as one of three key divisions, along with branded and generic drugs, in announcing a $28.5 billion restructuring of the company in April that involved selling off the vaccines and animal-health units and buying GlaxoSmithKline Plc’s cancer business.

“The promise here is the holy grail of vision care, to be able to replicate the natural functioning of the eye,” Jimenez said. “Think about a contact lens that could help the eye autofocus on that newspaper and then when you look up it would autofocus in the distance.”

Diabetes and data

Diabetes is a data-intensive disease. For those living with diabetes, managing their condition involves never-ending calculations: How much insulin to take to keep blood sugar in a targeted range, how many grams of carbohydrates are in a sandwich, or how an average monthly blood sugar reading fluctuates with different levels of exercise.

But unlike the math problems in school textbooks, there is often no clear answer to these questions. Given the numerous and complex factors that affect blood sugar — including food, physical activity, and sleep patterns — it’s not always clear what exactly occurs between a good blood sugar reading and a bad one.

To many Americans, this is an important question. Nearly 30 million Americans had diabetes in 2014, according to CDC estimates, though more than a quarter of them were undiagnosed. Another 80 million Americans were classified as “pre-diabetic,” meaning they will likely develop diabetes in the next decade if they don’t change their lifestyles.

Around 5-10 percent of these cases are Type 1 diabetes, in which a person’s body doesn’t produce insulin, and a person must take insulin to survive. The rest are Type 2 diabetes, sometimes called adult onset diabetes, in which a person gradually loses the ability to produce sufficient quantities of insulin.

In many counties in the U.S., more than 10 percent of the population has been diagnosed as diabetic.

Because it is so widespread, diabetes is incredibly expensive, costing the U.S. $176 billion in direct medical bills and $69 billion in indirect costs, including disability, work loss and premature death, in 2012.

Diabetes can’t be cured; it can only be treated. The goal is to keep blood sugar within a certain healthy range: If it dips too low, a person can faint or go into a diabetic coma. But too-high blood sugar results in wear and tear on the body that can lead to eye, nerve or kidney complications.

“It’s math all day long,” says Jeff Dachis, the founder of a new app for managing diabetes and a person living with Type 1 diabetes. “If I take too much insulin, I can die instantly, and if I take too little insulin over time, I’ll just die slowly. But if I stay in range, I can stay considerably healthy and unimpacted by diabetes.”

The widespread adoption of wearable health devices is diminishing some of this mathematical mystery. Many Americans are now using products like the Google Fit platform, the Apple HealthKit, or Fitbit to track their sleep, exercise and calories. And a coming wave of wearable technology and social media and mobile apps promises to transform how people live with and manage diabetes.

Diabetics had to painstakingly measure the sugar levels in their urine until the early 1980s, when the first glucose monitors were introduced for home use. (“My first One Touch meter was almost the size of a lunch box,” writes internet user coravh, who was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in 1966.) Today, most people with diabetes test their blood sugar with glucose meters, then administer insulin through an injection or an insulin pump, a device that sits under the skin and provides a continuous or programmed dose of insulin.

Technology companies are developing more innovative devices to continuously test blood sugar and provide readings and alerts, even while someone is exercising or sleeping. Abbot, Dexcom and Medtronic have developed continuous glucose monitors, which constantly measure blood sugar levels through a small sensor that is inserted under the skin, providing a lot more insight into how a good reading turns into a bad one. The devices still have drawbacks: They are expensive and only partially covered by insurance, if they are covered at all. And the FDA still recommends checking the readings against a glucose meter.

The next big technological step is an “artificial pancreas,” an implantable device which would monitor blood sugar as well as automatically deliver insulin. Researchers are developing small implants that can do both, eliminating the need for daily finger pricks and injections. Companies are also developing less invasive ways to measure blood sugar. For example, Google and Novartis AG’s Alcon unit

(see sidebar) are partnering to develop a contact lens that monitors glucose contained in tears and transmits the data through a tiny antenna. But these high-tech devices will be expensive, and may not be commercially available for years.

In the meantime, diabetics may be able to learn a lot more about their condition by organizing and sharing their data. Dachis, the co-founder of digital marketing firm Razorfish, helped develop a new diabetes app that launched in the Apple App Store this week. Called One Drop, the free app includes a digital glucometer, tracking features, social sharing and food logging. The app combines glucose, food, insulin and physical activity in a simple relational data display, and allows people with diabetes to share and learn from other people around them, says Dachis.

Dachis says the app is an example of the emerging practice of “data-driven self-care.” With doctors, hospitals and pharmaceutical companies more focused on procedure-based sick care, he argues that data-driven self-care has an important role to play in keeping people well. “The health care industry has been one of the last to digitally transform, and more importantly it’s been one of the last to participate in the democratization of the tools of self-expression that the mobile phone has enabled for people,” he says.

Dachis is emphatic that One Drop will never share personal, identifiable data with someone outside the community, for example for marketing purposes. But he is hopeful about the potential that the data, stripped of ways to identify individuals, holds for diabetes research. “With a large-enough population base, you’ll start to see wildly relevant correlations or causality between all different kinds of behavior,” he said. “We can start to collect and analyze and correlate that to clinical trial study data or published research data and start to extract the insights for people who are struggling and trying to navigate from moment to moment.”