Hillary Clinton is presenting her extensive government experience as a major rationale for her presidential candidacy. When she debated Donald Trump on Sept. 26, she countered Trump’s questioning of her stamina with the riposte: “Well, as soon as he travels to 112 countries and negotiates a peace deal, a cease-fire, a release of dissidents, an opening of new opportunities in nations around the world, or even spends 11 hours testifying in front of a congressional committee, he can talk to me about stamina.”

Clinton’s campaign hopes that her long proximity to the presidency, her years as secretary of state and her two Senate terms put her in a dominant position compared to Trump, who has no government experience. President Barack Obama has said, “I don’t think there’s ever been someone so qualified to hold this office.” Comedian Sarah Silverman has joked that Clinton is “the only person ever to be overqualified for a job as the president.”

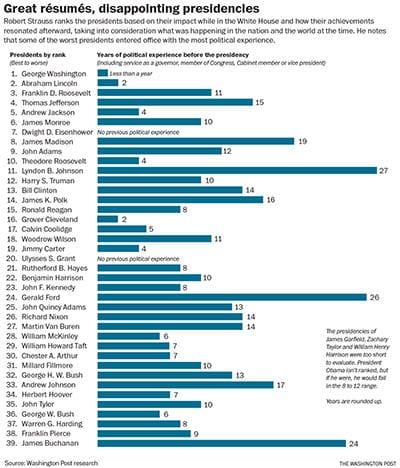

A look back at history, though, shows that lengthy experience in government hardly guarantees a magnificent presidency. Not even a good one. In fact, some of the worst presidents have been extremely qualified for the position – and some of the best, the least.

In the former category, take, for instance, James Buchanan. Buchanan had probably the lengthiest governmental résumé of anyone who has ever run for president. He was first a Pennsylvania state legislator, then a member of the U.S. House and, later, the U.S. Senate. He also served as U.S. ambassador to Russia and Britain, and as secretary of state. When he finally received the Democratic presidential nomination in 1856, he was 65, the second-oldest man to run for president up to that time. His backers emphasized his vast experience, especially when compared with that of his main opponent, John Fremont of the newly founded Republican Party.

Buchanan won in a walkaway, but his presidency was a disaster from the beginning.

Just before he was elected, Buchanan persuaded two Northern Supreme Court justices to go along with the Southern jurists to come to the decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which came out two days after his inauguration. Dred Scott held the Fugitive Slave Act to be valid and said the Constitution did not give any state the right to restrict slavery. The decision effectively paralyzed the nation after what had been a 20-year economic expansion, driven primarily by the railroads and the human and manufactured cargo it transported. Business owners worried that if they opened operations in formerly non-slave states, they could at any moment be out-competed by businesses using slave labor. Thus, businesses swiftly stopped expanding. Railroads declared bankruptcy and many large firms went out of business. Every bank in New York essentially shut down, refusing to honor scrip, but only gold and silver. The Panic of 1857 came on quickly and precipitously, and Buchanan’s answer was only that it was the fault of speculators, and that American grit eventually would solve the problem. It eventually did, when the need for armaments for the Civil War revived manufacturing.

At the end of Buchanan’s term – he said during the campaign that he would serve only one – he refused to support his major-party rival, Stephen Douglas, and the Democratic Party split into three, ensuring Republican Abe Lincoln’s election. In that interim before Lincoln’s inauguration, six states seceded. Buchanan said the Constitution gave them no right to do so, but he as president couldn’t stop them, thus ensuring the Civil War.

Buchanan may be the worst president, but he is hardly the only one whose deficiencies manifested in office despite an extensive résumé of government experience. John Quincy Adams is another good example. As a boy, Adams went to Europe with his father as an aide in many of the country’s first foreign negotiations. He went on to serve as a senator, minister to four countries and secretary of state. The five presidents before him all valued his experience, and his father, John Adams, and even his rival, Thomas Jefferson, relied on his advice. Yet his one term as president was so dismal that Andrew Jackson won 68 percent of the electoral votes when Adams tried for a second term. Adams was viewed as an anachronistic remnant of the Founders’ generation who thwarted westward expansion, while the “new” generation wanted to push the country on to the distant coast. He became the only former president to go back to the House, where he had a distinguished run for 10 more years.

Two other presidents who most often land in the bottom spots in historians’ surveys, Franklin Pierce and Richard Nixon, also had outstanding résumés. Pierce was a member of the New Hampshire legislature, rising to speaker, then a congressman and senator. He then refused President James Polk’s move to make him attorney general and became a Mexican War private, rising to brigadier general, all before age 43. The disastrousness of his presidency, though, was only short of Buchanan’s in that it did not result in a civil war. Pierce suffered by being a Doughface – a Northerner who favored the South. He wavered over whom to support in the battle over whether Kansas should be a slave state or free, and then pushed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which complicated the issue of slavery in the territories. Later, he supported the Ostend Manifesto (which was, ironically enough, written by his minister to Britain, James Buchanan), which promoted buying Cuba to be a slave state. His own party vilified him for that move and then refused to re-nominate him.

Then there was Nixon, who was a congressman, senator and vice president from 1947 to 1961, before becoming president. He had some good moments – getting the Environmental Protection Agency started and opening up China for trade – but instead of Waterloo, he had Vietnam, and then became the only president to resign in disgrace, over Watergate.

Meanwhile, many of our best-known and most beloved presidents entered office with fairly scant résumés. Consider George Washington, Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt. While Washington had little opportunity to have a governmental résumé – though he did lead the Continental Congress and the Continental Army – Lincoln and FDR had bare minimums. Lincoln had a few terms in the early Illinois legislature and one term in Congress, but he famously lost his run for Senate against Douglas and fell short in trying to become Fremont’s vice presidential running mate in 1856. FDR had one term as a state senator and another as governor of New York, but was also an electoral loser – in a Senate primary and, in 1920, as a vice presidential candidate.

Although it is true that these three faced some of the greatest crises in the nation’s history, so their presidential skills had the best chance of a grand result, each still succeeded in performing those executive miracles. They did not need to hark back to some experience in the legislature or a foreign mission to decide what to do. They relied instead on their personalities and their leadership skills.

Studies that have looked systematically at the relationship between experience and presidential success have found that most forms of experience touted in a candidate’s favor – legislative and diplomatic experience, leadership roles in the private sector and other forms of federal service – are not particularly useful when it comes to predicting positive terms in the White House. One study, by political scientist John Balz, even produced “weak evidence” that a stint in Congress may damage a president’s abilities in office, echoing the common sentiment that time spent as a Washington lawmaker may do more harm than good for presidential hopefuls. Some experience does appear helpful, however: Former governors, for instance, tend to finish their time in the White House with higher approval ratings than non-governors, and tend to perform better as presidents.

The presidency is a unique post, and it requires a combination of skills and talents that isn’t reflected in any other position. Experience as a senator or a Cabinet member or an ambassador may test a person’s problem-solving skills and negotiating skills and diplomatic skills, but it doesn’t necessarily provide opportunities for office holders to lead decisively, making momentous decisions mostly on their own. Even the most predictive of positions, such as gubernatorial posts, still fall short of the gravity and scope of the Oval Office.

Hillary Clinton has an impressive résumé of government service. But while her experience may help her win the White House, it doesn’t tell us much about how great a president she would be once she got there.

Robert Strauss is a journalist, educator, historian and author of “Worst. President. Ever. James Buchanan, the POTUS Rating Game and the Legacy of the Least of the Lesser Presidents.” He wrote this column for The Washington Post.