They were making fun of us. They were pointing their well-manicured, callus-free fingers at us and looking down at us.

That’s what we thought in 1985 when New York high-end fashion photographer Richard Avedon came to Texas to unveil In the American West, photographs commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum of Modern Art in 1979.

The photos were not the west we knew, or thought we knew. Avedon didn’t capture the wide open spaces, the scenic vistas or the noble spirits of the west. He took photos of people, real, hard-working men and women, usually at the end of a workday with weary faces and battered bodies.

Many of us didn’t like it. Where were the photos of good folk who gave alms to the poor, walked the straight and narrow and tithed to our church? Why didn’t he photograph all those good upright citizens of the west?

Because, we soon realized, there was more to us than that. The west was full of people with grit, tenacity and – at times – uncommon grace in the midst of daily, relentless hardscrabble existence. Initially derided by some critics and social arbiters of taste, soon lines were out the door. What was all the fuss about? The exhibit helped put the museum on the cultural map and the portraits are now considered classics.

And now they’re back with 17 of the portraits Avedon took in Texas from the original exhibit. It’s still a powerful show.

Who are we, really? That’s a tough question. Avedon made us ask it of ourselves.

Particularly compelling is the story of one subject, Billy Mudd, said John Rohrbach, senior curator of photographs for the Amon Carter.

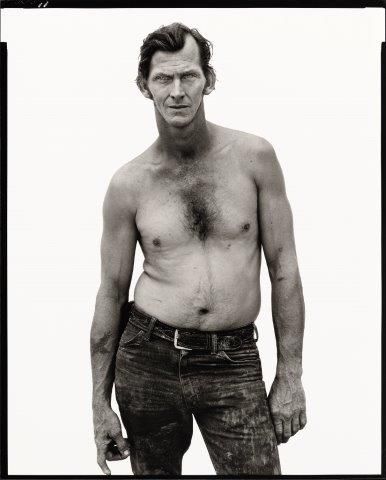

Avedon photographed Mudd, a hard-living, hard-drinking trucker photographed in Alto, Texas. Shirtless, Mudd looked like the kind of guy you’d definitely want on your side in a fight. A knife scar on his stomach drives that point home.

When Mudd attended the opening of the show in 1985, he didn’t know what to expect, parking his big rig in the parking lot across the street from the museum. Mudd saw his large, 56-inch by 45-inch photo and saw a “man who wasn’t going to live very much longer,” said Rohrbach.

As a result, Mudd changed his life a bit. Still a trucker, he’s straightened out his life and now has several grandchildren.

Much like Mudd, the exhibit changed the way we thought of ourselves. Texas – and the south and the west – was shifting inexorably rural to urban and that exhibit – with photos of laborers, drifters, housewives and ranchers – caught some of that metamorphosis.

The project changed Avedon, too. Accustomed to photographing people who wanted their portraits made – models, actors, powerbrokers and celebrities – the photographer had to work to coax complete strangers into standing in front of the unforgiving eye of his 8-by-10-inch Deardorff view camera.

But Avedon was used to getting what he wanted. Rohrbach said that when Avedon couldn’t penetrate the perfectly composed outer shell of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, he got an authentic reaction from her when he asked her bra size. Like that, the real Clinton appeared. Photo accomplished.

Five of the photos Avedon shot were taken at the annual Rattlesnake Roundup in Sweetwater. That set the tone for what has become a classic – but still somewhat controversial – exhibit.

It’s time to take a look at ourselves again.

In the American West

Amon Carter Museum of American Art

Feb. 25-June 2

www.cartermuseum.org