A painting of World War I

Reaches across time

When I first looked at it I was a little scared. Maybe more than a little scared. But I was also, like peeking between your fingers at a horror film, a little intrigued.

I was probably about 6 or 7 when I first noticed it. We were visiting my two great-uncles, John and Ed Chitwood, bachelor brothers of my grandmother. They lived in Mangum, Oklahoma – a small but still vibrant town in the early 1960s – in a small Midwestern frame house. There was the requisite storm shelter in the backyard, tornadoes being the Sooner State’s official mascot.

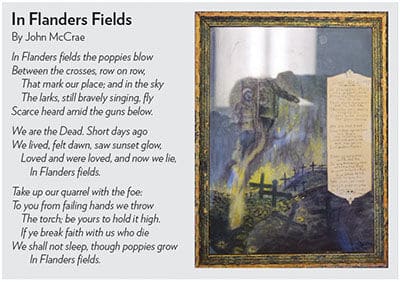

I was looking at the only original art in the sparsely furnished home, an 8X15 framed print depicting the horrors of war illustrating the In Flanders Fields poem by Dr. John McCrae from World War I. The print (if that’s what it is – it could be a colored pencil sketch, I’ve never taken it out of the frame for fear of damaging it) shows a graveyard with crosses on a dark, green hill and three soldiers – one obviously injured, but all grimacing as if in pain – ascending into the green, gray sky. Near the crosses are either yellow flames or – per World War I – a depiction of the dreaded mustard gas. Surrounding the crosses, in yellow, are fields of poppies, also mentioned in the poem. The poem, titled here We Shall Not Sleep (the original title of the poem) is written in pencil to the right of ascending solders and the graveyard.

I did not know what it was when I was young, only that I couldn’t look away. Even if I did look away, one glance and it was locked into my subconscious, escaping occasionally to remind me the world could be cruel, destructive and held no guarantees.

I didn’t even know that my great-Uncle John had served in World War I. Other than the print and the poem, there were no other indications John had been in a war. He was a small, quiet, slender man who drove his Dodge Dart into the town square every morning to have coffee at the local diner, then head to work as an accountant. Knowledge about his wartime experience wouldn’t come until later.

If you don’t know the poem, reprinted in a sidebar, here’s a little history, most of it taken from a great, detailed article by Rob Ruggenberg from Sheet Music Magazine in 2006. It was in that magazine because the poem was so popular it was put to music by several composers, including the “March King” John Philip Sousa. You can find some renditions of that version on YouTube, one by the United States Marine Band that is pretty stirring. I personally think the poem is well-suited to a treatment by Philip Glass, but Sousa’s is pretty nice, a little operatic, but more modern sounding than you would think for 1915.

The author, McCrae, was a surgeon attached to the Canadian 1st Field Artillery Brigade, and it was composed at the battlefront on May 3, 1915, during the second battle of Ypres, Belgium.

The day before, McCrae’s close friend and former student Alexis Helmer was killed by a German shell. We have pretty solid evidence on how quickly and when the poem was written.

On May 3, Sergeant-Major Cyril Allinson was delivering mail and he saw McCrae sitting at the back of an ambulance parked near the dressing station, writing the poem. McCrae had authored several medical textbooks and had written a few poems as well.

After he finished the 15 lines of the poem, in about 20 minutes, according to Allinson, he handed the poem to the mail carrier. Also there was Lieutenant Colonel Edward Morrison, who later became an Ottawa newspaper editor. He described the writing of the poem thus: “This poem was literally born of fire and blood during the hottest phase of the second battle of Ypres. My headquarters were in a trench on the top of the bank of the Ypres Canal, and John had his dressing station in a hole dug in the foot of the bank. During periods in the battle men who were shot actually rolled down the bank into his dressing station.”

And the crosses mentioned in the poem and in the painting? Continues Morrison: “Along from us a few hundred yards was the headquarters of a regiment, and many times during the 16 days of battle, he and I watched them burying their dead whenever there was a lull. Thus the crosses, row on row, grew into a good-sized cemetery.”

McCrae actually tossed the poem away. Morrison, being a smart editor even then, retrieved it and sent it to newspapers in England where it was published and found fame.

That second battle for Ypres was fierce, resulting in more than 9,000 casualties on the Allied side alone.

The battle is known for the first mass use of poison gas on the Western Front by the German army, hence the yellow colors in the painting.

Because of the poem, poppies – already associated with battles and the death of soldiers – became further popularized and the plant, particularly red poppies, became associated with Remembrance Day in many countries and Memorial Day in the U.S.

The final lines of the poem are somewhat controversial. They aren’t any plea for peace or nonviolence, instead talking about a “quarrel with the foe.” The author was not opposed to war, though he certainly regretted its result.

World War I was brutal, with over 7 million civilian deaths and 10 million deaths among military personnel. In a recent World War I documentary on PBS, it showed that, when peace was finally declared on Nov. 11, 1918, the soldiers quickly stopped fighting, came out of the trenches, shook hands and began playing soccer. They were tired of the death, carnage and destruction.

I didn’t know any of that as a 6-year-old. I just knew that print haunted me. We Shall Not Sleep, with its depictions of horror, death, suffering and muted beauty, held some deeper, buried mysteries that people didn’t talk about at barbecues, picnics and church socials.

I had asked my father about the painting and he quickly recited the first two stanzas of the poem, no doubt learned when he was a schoolboy or, perhaps, when he, too, stared into the haunting picture on the wall when he was a kid.

It wasn’t until I was older, living occasionally with my Aunt Lou Ann (I required a lot of parenting) in Washington, D.C. She spent her early years in Oklahoma near Ed and John, and from her I learned more about World War I and my family connection to it.

My aunt explained that John rarely talked about the war when she was young. But he did sometimes wake up with bad dreams, other times tearing up thinking about seeing fellow soldiers who had been gassed.

My father did recall one story Uncle John would tell others about the war. John was small and slight, but fast, so they made him a messenger boy, even though he was in his mid-20s when he was overseas. Sent to deliver a message during one battle, he had to crawl under barbed wire. He was wearing a backpack and it got tangled in the wire. The enemy, spotting a target that couldn’t escape, began firing at him. John fought his way out of the barbed wire and made his way to safety without any serious wounds. He couldn’t say the same about his backpack, which was destroyed in the fusillade of bullets.

John died in 1976 and I missed that small house in that small Oklahoma town that had streets named after presidents, from Washington up through, ironically, our World War I president, Woodrow Wilson. And, I never got to hear any stories about his experiences in the war. From some research I’ve done more recently, I know he did his basic training right here in Fort Worth at Camp Bowie and that he was wounded several times while overseas.

Also doing some research, I found a print similar to the one from my uncle’s wall. It was a cover to some sheet music for another song that uses the poem at its text, this time by Charles Gilbert Spross. The print is slightly different and the poppies are bright red. It could be that Uncle John’s print was faded, but it’s hard to tell. I also learned that many times copies of the song, along with prints of illustrations of the poem were sold to soldiers returning from the war and/or during Memorial Day events. That’s probably where John got his copy. But it obviously spoke to him of his memories during that time.

It was sometime after John died that my aunt said that a relative I didn’t even know had sold John and Ed’s house in Mangum, storing the contents in case other family members wanted anything.

I was attending the University of Maryland at the time and I remember we were driving through Virginia, continuing our tour of American history sites. (Hint: History is all over Virginia and the Washington, D.C. area; you don’t have to drive very far).

For some reason, probably because you can’t forget something that gave you nightmares as a kid, I mentioned the We Shall Not Sleep painting. My aunt remembered it, too, and wondered whatever happened to it. Maybe, she thought, it was being stored with all the other contents of Ed and John’s home.

I thought nothing more about it. Well, I’m sure my subconscious did, but only to drag up the images in some horrific nightmare.

So I was surprised a few years later when I visited my aunt, who was ailing at the time, barely getting around.

“I’ve got something for you,” she said, shuffling off to a back room. She returned handing me Uncle John’s Flanders Field print.

You get a lot of gifts in your life. Some of them never get out of the box, some of them (cupcakes perhaps) last only a few minutes. This was truly a gift of thoughtfulness and love. Only someone who cares, and cares about you, would go to the trouble to track down something that you mentioned in a casual conversation 10 years earlier.

Hard to believe that something born from such a terrible, destructive place found its way back to me, a century later, through an act of thoughtfulness and love.

And, as for never having gotten to ask Uncle John about World War I, he now reaches across time to speak to me, each time I gaze upon We Shall Not Sleep. I can hear you, Uncle John.

We Shall Not Sleep

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields. – John McCrae