Fiery oratory, sharp political skills marked career of Fort Worth congressman

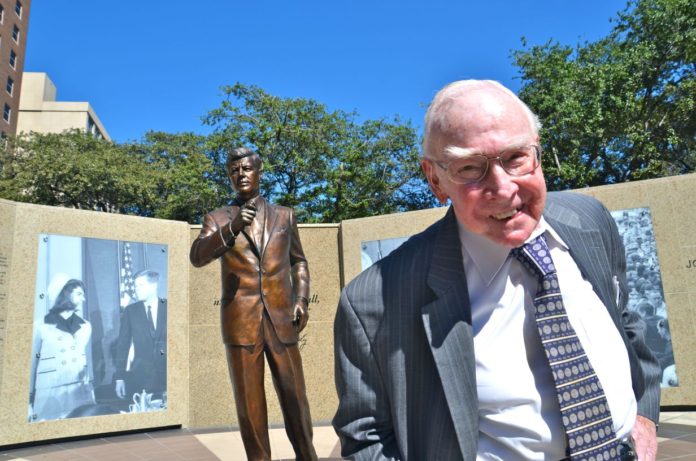

Jim Wright, Fort Worth’s congressman for 34 years, a political powerhouse and former speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, died on May 6 at the age of 92.

Wright, a hard-driving 18-term Texas Democrat who, in the tradition of fellow Texan Sam Rayburn, expanded the influence of the speakership. In his career, Wright alternately charmed and tangled with presidents, fellow politicians on both sides of the aisle and foreign officials, all the while bringing home federal dollars to his beloved Fort Worth.

And bring them he did, says Jim Riddlesperger, a political science professor at Texas Christian University who worked with Wright when the former speaker taught there.

“Jim Wright was involved in just about anything that happened in Fort Worth from 1954 to the mid-90s,” he said.

Longtime friend Dee J. Kelly, founder of the Kelly Hart & Hallman law firm, said many have forgotten how much he meant to the city.

“From our interstate highway system, from American Airlines moving their headquarters from New York City to Fort Worth to the magnificent D/FW Airport, Jim Wright played an essential role, not only in the development of the airport, but also in protecting it from competition during its formative years, to Alliance Airport, our first industrial airport, to Bell Helicopter and its tilt-rotor program and General Dynamics with its F-16 Fighter program,” Kelly said.

Elected to Congress in 1954, Wright was a dominant and seemingly indomitable figure in the House, where he had risen from obscure Fort Worth congressman in the 1950s to majority leader under Speaker Thomas “Tip” O’Neill of Massachusetts in the 1970s.

In a House career spanning 34 years, Wright thrust himself most forcefully into the limelight when he succeeded O’Neill as speaker in 1987. Fiery and intense, Wright could not have been more different from the affable, backslapping O’Neill. Wright was known for his fiery oratorical skills, which belied his lack of a college degree, noted TCU’s Riddlesperger.

Wright envisioned a muscular speakership that influenced and generated foreign policy, historically the sphere of the White House and the Senate.

He antagonized the Reagan administration most boldly over its Central America policy, particularly aid to Nicaragua, which was suffering from a protracted civil war. Wright was crucial in brokering a deal that led to peace and democratic elections in Nicaragua.

Resignation

Poised to become one of the most influential speakers in decades, Wright endured a yearlong investigation by the House Ethics Committee that eroded his power and led to charges that focused on financial gain in violation of congressional rules.

He was the fourth speaker to resign the office, but the first to step down amid allegations of ethical impropriety. His downfall was a pivotal moment in the rise of Rep. Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., who led the fight for the ethics investigation, and in the House’s transformation from a proudly collegial institution to one mired in partisan rancor.

In 1989, as the accusations piled up, Wright told those who had elected him speaker that he was prepared to resign. He offered only a meager defense of his actions, quickly turning to questioning his accusers’ motives and decrying what he called “this manic idea of a frenzy of feeding on other people’s reputation.”

His voice broke at times and tears appeared during his speech.

“It is grievously hurtful to our society when vilification becomes an accepted form of political debate, when negative campaigning becomes a full-time occupation, when members of each party become self-appointed vigilantes carrying out personal vendettas against members of the other party,” Wright lamented. “In God’s name, that’s not what this institution is supposed to be about.”

In the end, Wright offered to resign to spare the House what he called “distractions” and asked that both sides resolve to “bring this period of mindless cannibalism to an end.”

Wright was not someone likely to generate widespread sympathy during an ethics probe. He had a reputation as a hot-tempered micromanager, and he once nearly came to fisticuffs with a California congressman over a procedural matter.

But he endeared himself to fellow Democrats by stumping for them in their districts and raising money for their campaigns. He also held one of the most popular functions on the Hill, an annual barbecue for which he dressed as a cowboy and played the harmonica.

Although his approach to public speaking tended toward the stentorian, he relished folksy aphorisms and jokes. He memorably described the rhinoceros as one of God’s mistakes: “Here is an animal with a hide two feet thick and no apparent interest in politics. What a waste.”

Path to power

Wright’s sharp mind and sharp elbows helped clear his path to power.

“His goal was to make the speakership equal to the presidency,” said historian John Barry, whose 1989 book “The Ambition and the Power” focused on Wright. “He was certainly on the way to doing that.”

Although he often pitted himself against the Reagan administration on legislative matters, no issue brought Wright as much attention as the fight over aid to Nicaragua. It became one of the most divisive public debates in Washington.

The Reagan administration had placed the anti-Sandinista, anti-communist contra rebels in Nicaragua at the center of its Central America foreign policy, describing them as “freedom fighters.” But many Democrats, including Wright, considered the contras no better than terrorists.

In the mid-1980s, the White House found itself immersed in scandal involving illegal arms sales to Iran and illegal aid to the contras. It came to light that U.S. officials had sold weapons to Iran to win the release of U.S. hostages in the Middle East and then used some of the profits to support the contras after Congress had prohibited giving them military aid.

In July 1987, a White House aide approached Wright about joining Reagan to broker a peace deal in Central America. Wright agreed, though many Democrats sensed it was a trap.

According to Barry’s book, the White House enlisted Wright’s support for a proposal it expected Nicaragua to reject, thinking it could then point to the failure of diplomacy to bolster the case for funding the contras.

After the Central Americans agreed on an accord, Wright began holding peace talks in Washington with Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega and Cardinal Miguel Obando y Bravo, the archbishop of Managua, who was seen as a possible mediary in the civil war.

The White House had refused to meet with Ortega during that visit, insisting that he negotiate with the contras before any U.S. intervention. Wright scolded the Reagan administration for being “literally terrorized that peace might break out” in Central America and added that many leaders in that part of the world preferred negotiating through him because they have “the unfortunate impression that the administration treats them as inferiors.”

After the Central American leaders drafted their own peace agreement, Wright offered his unequivocal support. The accord helped end Nicaragua’s long civil war and led to democratic elections in 1990.

“He was absolutely critical,” said William LeoGrande, an expert on Latin American politics at American University. “The Central American leaders looked to Wright for mediation, for advice and for support … They felt he was committed to make it work.”

Wright resigned on June 1, 1989, and his chief deputy, Tom Foley of Washington state, assumed the speakership.

Gingrich went on to become speaker after the Republican takeover of the House in the 1994 midterm elections. But ethics charges would tarnish the end of his tenure in Congress, as they had Wright’s, and he resigned in 1999. When Gingrich, as speaker, faced criticism from the ethics committee over a $4.5 million book advance, Wright tweaked his former antagonist. By comparison, Wright said, his own book royalties were “small potatoes.”

Biography

James Claude Wright Jr. was born in Weatherford on Dec. 22, 1922. His father was a salesman, and the family moved frequently around the region.

During World War II, Wright was a B-24 bombardier and flew 30 bombing missions over Japan. He recounted his war service in his 2005 book, “The Flying Circus: Pacific War – 1943 – as Seen Through a Bombsight.”

After returning from combat service, Wright won election to the Texas Legislature. He supported an anti-lynching bill, abolition of the poll tax and the admission of black students to the University of Texas law school.

His progressive views, far to the left of his constituents, cost him re-election, but he won two terms as mayor of Weatherford before winning a House seat in 1954. He was assigned to the Public Works Committee, where he wielded influence over interstate highway construction just as the program was commencing.

Over the years, he fought for a variety of development programs that benefited his state and became a reliable supporter of the Texas oil and gas industry. He also supported U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, with political analysts noting that his district was a hub of defense contractors.

On civil rights, he amassed a complicated legacy. He voted against the hallmark 1964 Civil Rights Act because, he said, a yes vote that year would have ended his political career. He apologized for the vote many years later and voted for key civil rights legislation in 1965 and 1966.

Wright twice ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate in the 1960s – including a bid for Lyndon B. Johnson’s vacated seat after Johnson became vice president – and instead advanced to the House leadership.

When O’Neill became speaker in 1976, vacating the majority leader’s office, Wright put his hat in the ring, along with three other contenders.

Two liberal democrats were vying to succeed O’Neill. Wright said he saw an opening as a respected moderate whose state had one of the largest Democratic delegations. Wright positioned himself as everybody’s second choice and won by a single vote on the final round.

After leaving Congress, Wright took to the speaking circuit. He wrote a column for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and taught a political science course at TCU. In the late 1990s, he became ill with tongue cancer, which slurred the old orator’s speech. He had to relearn diction.

His first marriage, to Mary Ethelyn Lemons, ended in divorce. Their son, Parker Stephen Wright, who had Down syndrome, died in 1958.

In 1972, Wright married Betty Hay, a former staff member for the House Public Works Committee. Besides his wife, survivors include four children from his first marriage.

Reflecting on his political career soon after his resignation from the speaker’s post, Wright told The Washington Post: “I think I was probably obsessed with the notion that I have a limited period of time in which to make my mark upon the future, make my contribution, whatever it may be, and, therefore, I must hurry.

“Maybe I was too insistent, too competitive, too ambitious to achieve too much in too short a period of time, and anyway I couldn’t have changed.”

The report includes material from the the Washington Post, the Associated Press and from Robert Francis and Bill Thompson of The Fort Worth Business Press.