The Kimbell Art Museum opens Turner’s Modern World Oct. 17, a sweeping and stunning presentation of the work of British artist J.M.W. Turner, whose works transformed the artistic styles of his lifetime – 1775-1851 – into the modern style patrons are accustomed to seeing in today’s museums.

The Fort Worth show is the U.S. premiere of the exhibition and the first major exhibition of Turner’s painting in North Texas in more than a decade. It runs through Feb. 6, 2022.

Turner made his early reputation as a landscape painter and a watercolor artist, but it was his interest in portraying the industrializing world that established him as one of Great Britain’s greatest artists.

“Born in 1775, Turner witnessed spectacular transformations in modern life. A keen observer of history, Turner immortalized these dizzying changes and current events in vivid and dramatic compositions with expressionistic brushwork that conveyed his sense of uncontrolled wildness,” said Eric Lee, director of the Kimbell Art Museum.

The exhibition features oils and watercolors from Tate Britain, home of the Turner bequest and other British lenders, as well as paintings from The Museum of Fine Arts Boston, The Cleveland Museum of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts Houston, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Yale Center for British Art.

“In the exhibition you will see more than a hundred paintings and watercolors that reflect events of the first half of the 19th century. Military battles, political and social upheaval, technological innovation, and more all unfolding in Turner’s dramatic and revolutionary style,” Lee said.

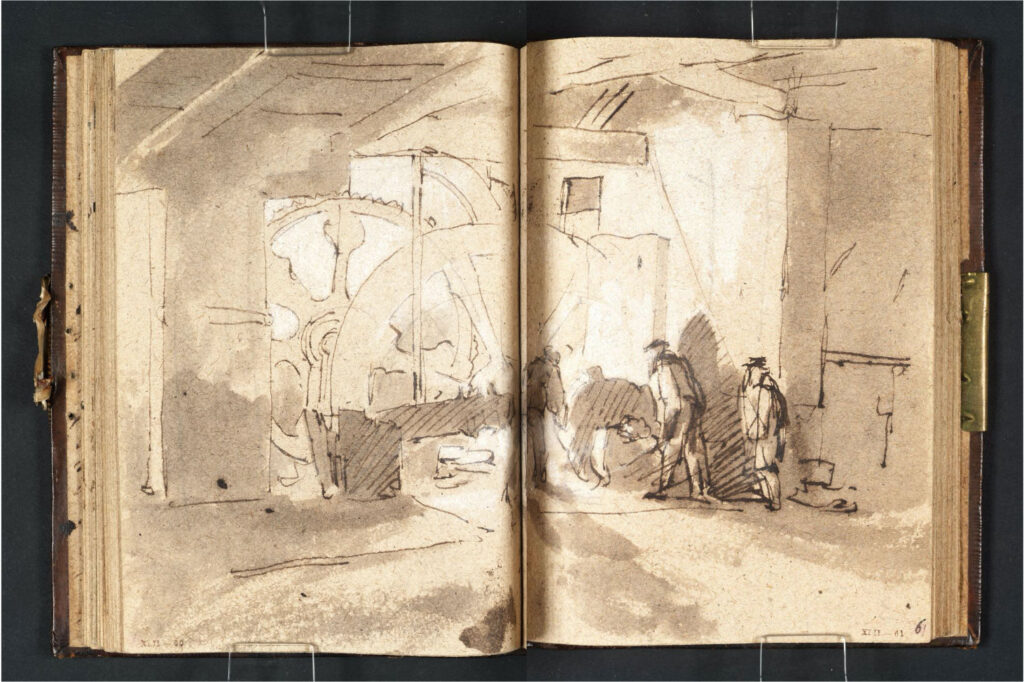

Turner was born in the early years of the Industrial Revolution and witnessed spectacular technological innovations and the mechanization of modern life, often making sketches in small notebooks, later to be turned into vivid and dramatic compositions.

He explored British life with art such as The Interior of a Tilt Forge from one of his pocket sketchbooks and British politics, in such works as The Northampton Election. He depicted the great land and sea battles of the Napoleonic Wars – Trafalgar and Waterloo – with monumental canvases to bring current history to his public.

“In his final decades, Turner produced astounding works that melded contemporary subjects with a highly animated style, an accomplishment that established him as one of the founders of modern art,” Lee said. “It created a dynamic, inspired and comprehensive testament to his own era. He was not only a witness to modernity, but an interpreter and champion for his generation.”

Had Turner produced only the landscapes in oils and watercolors where he started, he still would be recognized for his great art, said Exhibition Curator George T.M. Shackelford, deputy director at the Kimbell.

“But as you’ll see in this exhibition, he rose beyond … his beginnings, and created an early body of work that was truly influential. More influential in many ways than any other artist of his era,” Shackelford said.

The exhibit displays many watercolors.

“Turner begins in a very conventional way, painting beautiful watercolors of the type that were easily sold, and very much the taste of British collectors at the time, and often showed picturesque spots in Britain.

“But at the same time that he’s making those, he’s also making some remarkable works. And we’ve gathered them here at the center (of the exhibit) just to get you started with thinking about what it meant to choose modern subject matter,” Shackelford said.

In three displayed watercolors and two sketch books, Turner turns to industry, illustrating the growing industrial life in Britain with a blacksmith’s forge, a tannin foundry and a lime kiln where limestone was burned to create lime for cement.

Turner carried the small sketchbooks in his pocket to be able to jot down his impressions of what he’d seen on site, probably going back to the studio to concoct some of the watercolors from his imagination.

“So he’s early on engaging with subjects that were seldom represented in British art in this period. And it’s a testament to his early interest in painting things that were not simply elegant views of the landscape, but also were really focusing on people and places in modern times,” Shackelford said.

For most of Turner’s early lifetime, England was at war with France. Scenes from that time are displayed in a section of the exhibit called Home Front, depicting life in Britain while its soldiers were engaged in battle on the continent.

“For instance, there was a time when food was hard to get in Britain, and people were encouraged to start eating turnips, which had previously been food for cattle,” Shackelford said.

One painting shows peasant farmers plowing turnips. But there is a second meaning that would have been so clear to a viewer in the early years of the 19th century.

“At the same time that he was promoting this kind of farming, the King and the Parliament had allowed wealthy land owners to fence in their land, or to delineate their properties. And so a large number of semi-public farming lands that had guaranteed a place for these peasants to farm and sustain themselves were no longer available to them,” Shackelford said.

“So there’s a social commentary going on in this painting, between the poor in the foreground and the rich and the King in the background. It’s about a subject that we’re all keenly aware of today, of income inequality.”

During that grinding period of constant warfare, Turner painted The Battle of Trafalgar, as Seen from the Mizen Starboard Shrouds of the Victory, where Lord Nelson defeated the combined naval forces of France and Spain. Turner’s painting consolidates the battle into a single image.

Two of Turner’s sketch books document his research that resulted in paintings about the decisive battle of Waterloo.

Shackelford notes that the starkness of the scene may have been unpopular In Turner’s time because it was about the tragic consequences of war rather than the glory of victory.

In October 1834 the Houses of Parliament caught fire, an event Turner also painted.

“It’s a bit like the burning of Notre Dame. It’s an event that was tragic and yet also people had to go and look. And so, just as around Notre Dame people stood and watched as the cathedral was burning, here, thousands of people are gathered on the banks of the Thames.

“We know that Turner was among them. It’s possible that he actually hired a rowboat to get out into the Thames to see closer. But he imagines himself on the South Bank of the river, looking upriver toward the burning of the Houses of Parliament,” Shackelford said.

But the painting is significant for another reason.

“When you get close to this painting, you’ll also see Turner’s trademark brushwork beginning to emerge here. We’re in the middle of the years of the 1830s and this is the moment when Turner starts to let his brushwork be so visible and his own hand is so evident in the making of the work of art. So that when you look at it, you got the sense of the artist interpreting the subject and that presence of the artist was still enormously powerful,” Shackelford said. “You’re very aware of his use of a knife, for instance, to put paint on in slathers as well as with a brush, detailing little flicks of flame or the way the reflection of the light hits the water.”

Current events – and perhaps social commentary – were of interest to Turner.

Shackelford cites a painting called Disaster at Sea, perhaps destined for exhibition at the Royal Academy and believed to be inspired by the wreck of a ship called The Amphitrite, which left Britain bound for the penal colonies in Australia with a cargo – Shackleford says he uses that word advisedly – of female convicts and children.

“I say ‘cargo’ instead of ‘passengers’ because these people were being hauled out to Australia to spend the rest of their lives in punishment. The ship foundered off the coast of France. And it would have been possible for everyone on board or most everyone on board to have been saved,” Shackelford said.

But the captain refused help because he feared that if his “cargo” were to be put onto land that it would escape, and he would have failed in his mission of taking those convicts from Britain to Australia.

“So, in the hope that the rising tide would release the ship from its foundered position, he forbade anyone to go off the ship. And as a consequence, everyone died, all but three members of the crew, the captain died and all the women and children died,” he said.

“And of course, this was a huge scandal. We believe that this may be the inspiration for this painting and we don’t really understand why Turner never brought it to completion. It seems like it would have been such a spectacular painting.

“He uses the same idea of juxtaposing warm passages here in the foreground, the turning water over the bodies of the dying and dead, and juxtaposing it with the cool background, a very distant horizon with perhaps a moonrise. A painting with flares that seem to fall from the sky, these beautiful touches of very thick paint that seem like blowing embers falling from the sky through the clouds,” Shackelford said.

“And what a moving painting it is to us even now. It’s come to be one of my favorite paintings in the show. And I think it’s because of this combination of Turner’s gesture, the way he paints it and the very touching subject matter, moving subject matter, that makes it so powerful,” he said.

From the 1790s to the end of Turner’s life, Britain’s economic and political fabric underwent continual and far-reaching alterations.

Industrial development brought machines to the workplace, made possible the spread of steam power and resulted in a massive redistribution of the rapidly growing population from the country to newly industrialized cities.

And that gave Turner new material for both paintings and visual commentary on quality of life in the industrial age.

The invention of the steam engine at the end of the 18th century, and its adoption for industry in the first two decades of the 19th century provided Turner with much inspiration.

“The steam engine changed British travel rapidly. Not only were steamships a much more effective way of moving from place to place, and indeed across the oceans, but they were coupled with the arrival of the railroad which changed the way people moved throughout Britain,” Shackelford said. “A journey that might have taken days in a carriage could be accomplished in one day on a railroad train.”

Turner’s juxtaposing a steamboat with a sailboat in a painting is his commentary on how the new world is replacing the old way of doing things, how steam power is replacing sail power.

He paints coal miners and haulers and industrial towns covered in steam and smoke.

“It was really the Industrial Revolution that created the famous London fogs. They didn’t exist before the burning of all that coal in the city, and the arrival of all those factories that were putting out all kinds of noxious gases. And Turner was really, I believe, commenting … on how London and the British landscape was changed by the arrival of the industrial age.”

Shackelford calls particular attention to the painting Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth.

“So many people expect that Turner will be all about whirlwind, and this painting gives you exactly a whirlwind, a maelstrom of storm surrounding this poor steamship that’s out fighting against the wind and snow, and the rising waves,” Shackelford said.

This and similar images are a reminder that nature is always going to win.

“All these paintings have that intensely romantic era emotion, and they’re meant to provoke emotion in us. We’re supposed to feel along with the painter, the drama, the sublime fear, terror,” he said.

“All of these emotions are meant to be what we’re experiencing when we look at Turner’s paintings. Turner said he put forward the story that he had had himself lashed to the mast of a steamboat out in the snowstorm. We think it’s a bit of fiction, that he actually never did it, but it was part of the marketing, if you will, of his works to have gone through the experience that he represented so vividly in paint,” Shackelford said.

Turner’s arch competitor, John Constable, on seeing Turner’s paintings said that he painted with steam.

“I think that was great praise. Constable was really admiring the way Turner seemed to be able to take something as ineffable and difficult to represent as vaporized air and be able to render it and use it as part of his toolbox,” Shackelford said.

Many of Turner’s paintings were never released and became available to the public only after his death.

“Suddenly, the world was aware of this side of Turner, which is what we think of as the most modern side of Turner. This is the side of Turner that has kept him living on in the imagination, particularly in the imagination of painters. And it’s to these kinds of paintings that many modern painters gravitate most readily,” Shackelford said.

Even though a later abstract painter might never have seen these paintings, they might have seen the work of another artist who had seen these paintings and had been influenced by them.

“Through Monet and others to the most beautiful explorations of light in the work of color field artists in the middle years of the 20th century, we find there’s a fascination with the rendering of light and color through paint, through the materiality of paint,” he said. “And this is something that Turner plays an extraordinarily important role in – this artistic movement.”

Turner’s Modern World

October 17, 2021–February 6, 2022

Admission to Turner’s Modern World:

- $18 for adults

- $16 for seniors, K–12 educators, students and military personnel

- $14 for ages 6–11

- Free for children under 6 and $3 for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients.

Admission is half-price all day on Tuesdays and after 5 p.m. on Fridays. Admission to the museum’s permanent collection is always free.

The Kimbell Art Museum Hours

- Tuesdays through Thursdays and Saturdays – 10 a.m.–5 p.m.

- Fridays, noon–8 p.m.

- Sundays, noon–5 p.m.

- Closed Mondays, New Year’s Day, July 4, Thanksgiving and Christmas.

For general information, call 817.332.8451.

The exhibition is organized by Tate Britain in association with the Kimbell Art Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities and by the Texas Commission on the Arts and the Fort Worth Tourism Public Improvement District. Promotional support is provided by American Airlines, NBC 5 and PaperCity.

The curator for the exhibition at the Kimbell Art Museum is George T.M. Shackelford, deputy director.

3333 Camp Bowie Blvd.

Fort Worth, 76107

www.kimbellart.org